The curveball was introduced to baseball in the early 1870s, and changed the face of the game. Pitchers, for the first time, threw strikes that moved across the plate and down, curving away from right-handed batters, frequently baffling hitters. But were the first curveballs thrown in a high school game thrown at Williston?

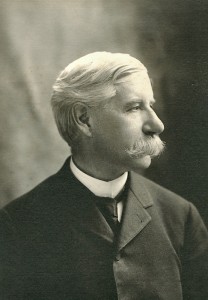

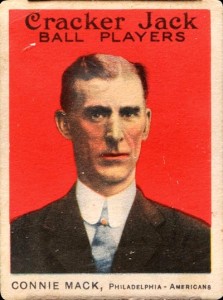

It’s a good story, related by none other than legendary Philadelphia Athletics manager Connie Mack. In his My 66 Years in the Big Leagues (Philadelphia: Winston, 1950), Mack recalls, “The first man to pitch a curve-ball game was Charles Hammond Avery, Yale 1871-75, popularly called Ham Avery, and the first curve-pitched college game was played between Yale and Harvard at Saratoga, New York, June 14, 1874, the week of the college boat races. Avery pitched for Yale and won by the score of 4-0, the first shutout ever scored against Harvard.”

It’s a good story, related by none other than legendary Philadelphia Athletics manager Connie Mack. In his My 66 Years in the Big Leagues (Philadelphia: Winston, 1950), Mack recalls, “The first man to pitch a curve-ball game was Charles Hammond Avery, Yale 1871-75, popularly called Ham Avery, and the first curve-pitched college game was played between Yale and Harvard at Saratoga, New York, June 14, 1874, the week of the college boat races. Avery pitched for Yale and won by the score of 4-0, the first shutout ever scored against Harvard.”

Mack cites as his source of information his lifelong friend, Frank Blair, Williston Seminary class of 1876, Amherst 1880. The two had grown up together in North Brookfield, Mass. Mack continues, “In his first year at Williston Academy [sic], in 1873, one of Blair’s chums was Charles Francis Carter, a left fielder who went to Yale in 1874, and the following year played on Avery’s famous Yale team. Stories began to drift back to Williston that Avery was a wonder, for he had introduced something new into baseball—a curve ball that was puzzling batters and was proving very difficult to hit.”

“One day in 1876 Blair was examining the condition of the diamond on the [Williston] campus. He spied Carter coming up the street from the station. Carter spotted Blair at the same moment, and vaulting the fence, shouted to him, ‘I can pitch curves! Avery taught me!'”

“With that, Carter took a baseball from his pocket, laid aside his overcoat, and began to show [Blair] how the mystery was performed. Carter, having passed on the instructions to Blair, picked up his overcoat and started for the train back to New Haven. He had seemingly accomplished his mission! Blair was eager to pass on the secret to the Williston pitcher. The result? Williston [Seminary] placed on the diamond the first curve pitcher used in any prep school in the United States.” Continue reading