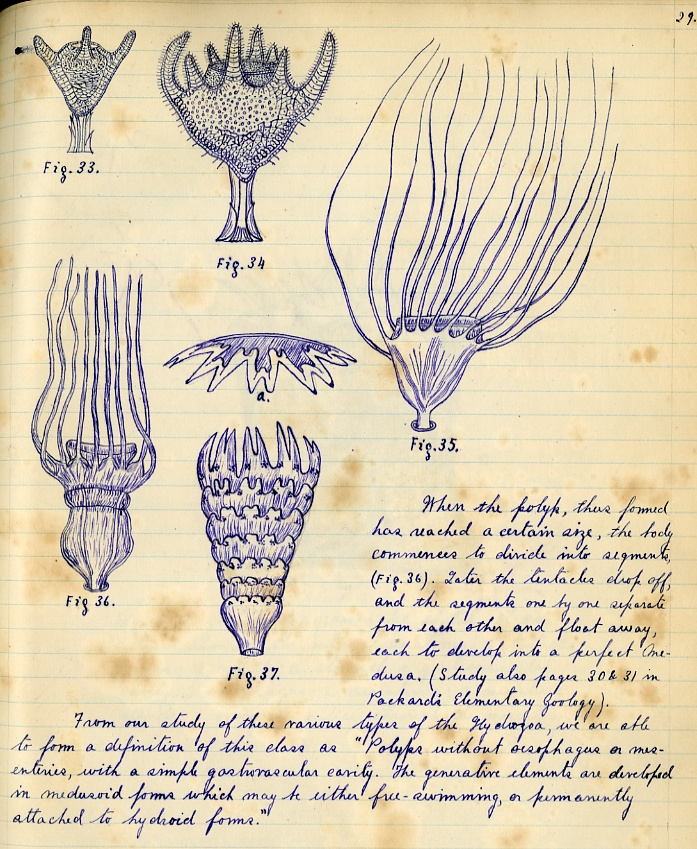

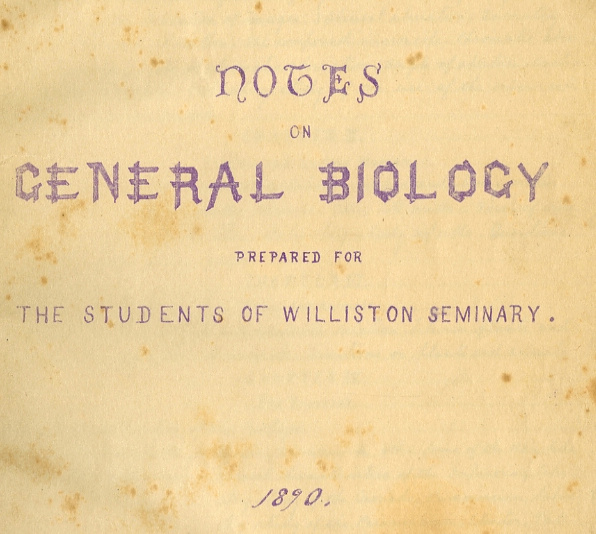

The Archives Acquire a Fascinating Record of Science Teaching

It was one of those phone calls that vastly improves one’s week. “My name is Will Wyatt – I’m a dentist in Texas. I have what appear to be a notebook from a Williston biology class, dated 1890. Would you like it for the Archives? If so, I’d be happy to donate it.”

Would I like it? That would have been an understatement. Among the more important things we collect are examples of academic work: what was studied, and how it was taught, going back to our beginnings 175 years ago. We actively seek current student work, as well as that from the past. Consider: all the other things we save and cherish – theater photos, box scores, school newspapers, and dozens of other categories, most of them well-represented in this blog, wouldn’t even exist without the academic program. It provides a context for everything else in our daily lives at a busy school. Academics are the most important thing we do at Williston.

So yes, we were thrilled to accept Dr. Wyatt’s generosity – the more so given the age of the item. It is relatively easy to lay hands on student papers from 2015. Anything from the 19th century is another story entirely. And as shall be seen, this particular item is very special.

The document is a set of teaching notes for an 1890 Williston Seminary biology course taught by William Tyler Mather (1864-1937). Mather, Williston class of 1882, went on to Amherst College, graduating in 1886. He taught at Leicester Academy, 1886-1887 then, like many Williston and Amherst alumni, returned to Williston to teach (1887-1893). During this time he also completed a master’s degree at Amherst (1891). In 1894 he entered Johns Hopkins University, earning a Ph.D. in physics in 1897. In 1898 he became Professor of Physics at the University of Texas, Austin, where he remained the rest of his life. (This would tend to partially explain how a set of teaching notes found their way from Easthampton to “a very eclectic used book store” in San Antonio, where Will Wyatt purchased them in the 1980s.)