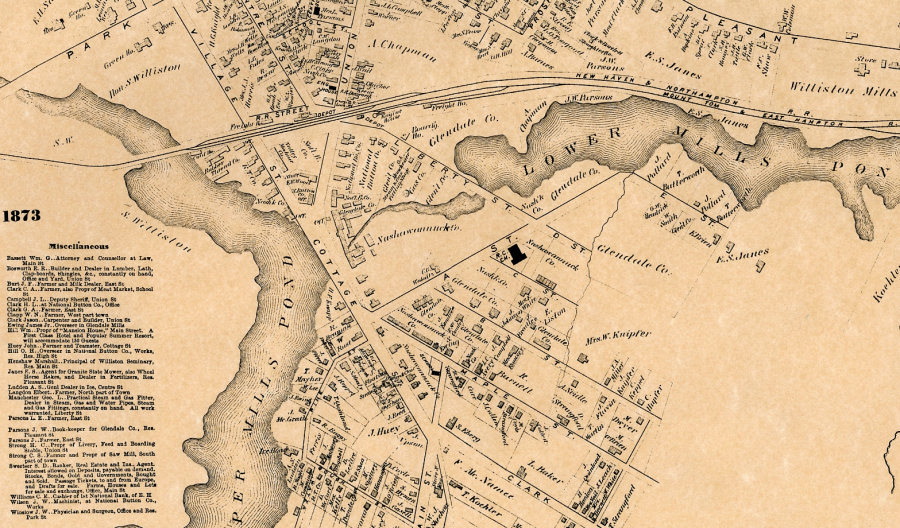

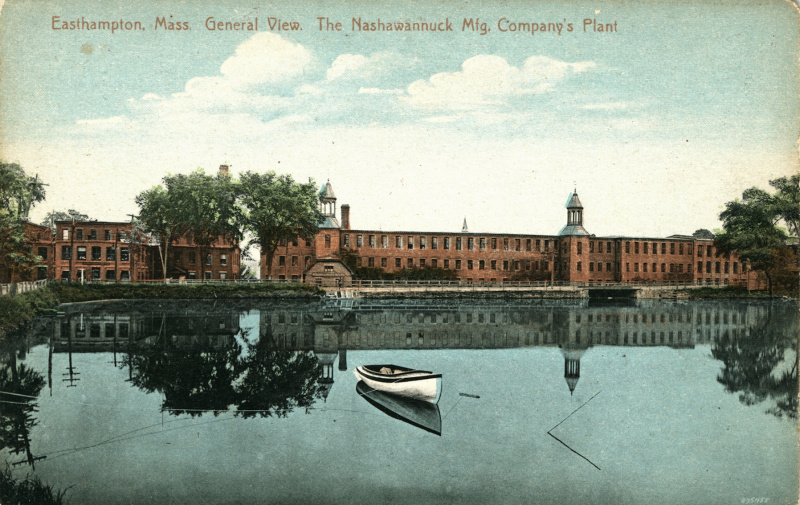

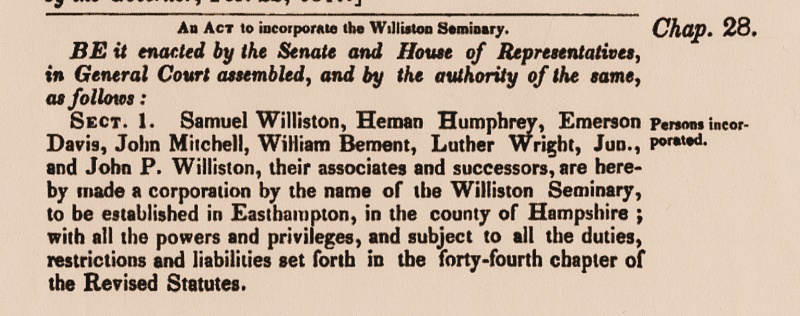

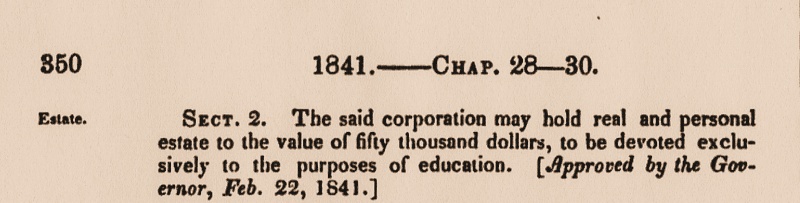

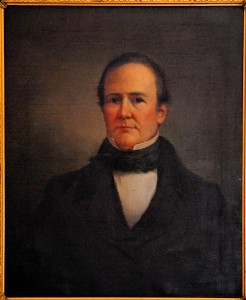

It was one small item from a legislative day filled with similar minutiae. But 175 years ago, Easthampton manufacturer Samuel Williston and a few associates petitioned the General Court to form a corporation “devoted exclusively to the purposes of education.” On February 22, 1841, the legislature approved the petition, Governor John Davis signed it into law, and Williston Seminary came into being.

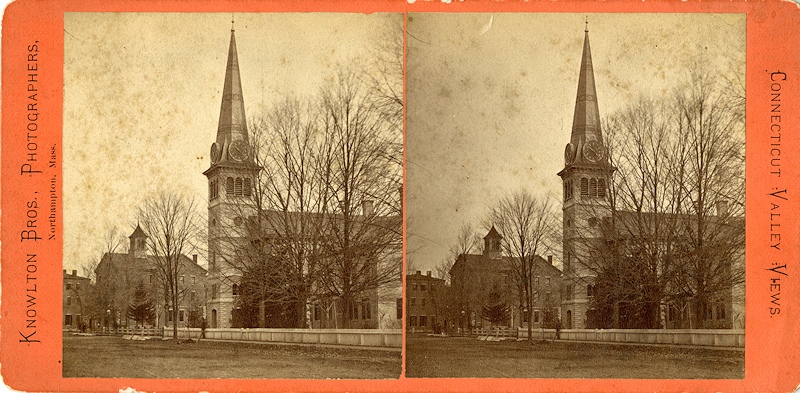

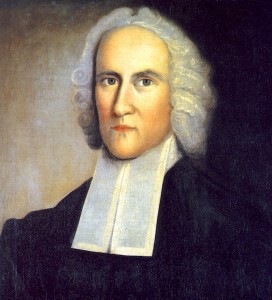

Samuel Williston, like Governor Davis, was an influential member of the Whig Party — and Williston, perhaps conveniently, was a month into his only term as Easthampton’s Representative. Of the other incorporators, Heman Humphrey was President of Amherst College; Emerson Davis, Minister of the First Congregational Church in Westfield, Mass., John Mitchell, Pastor of the Edwards Church, Northampton; William Bement, Pastor of the Easthampton Congregational Church. Luther Wright (see 1848: Responding to the World) was Samuel’s boyhood friend, lately the Principal at Leicester Academy, and would serve as the Seminary’s first Principal. The only non-clergyman in the group was Samuel’s younger brother John Payson Williston (see Firebrand). These men would become the core of Williston Seminary’s first Board of Trustees.

Samuel Williston, like Governor Davis, was an influential member of the Whig Party — and Williston, perhaps conveniently, was a month into his only term as Easthampton’s Representative. Of the other incorporators, Heman Humphrey was President of Amherst College; Emerson Davis, Minister of the First Congregational Church in Westfield, Mass., John Mitchell, Pastor of the Edwards Church, Northampton; William Bement, Pastor of the Easthampton Congregational Church. Luther Wright (see 1848: Responding to the World) was Samuel’s boyhood friend, lately the Principal at Leicester Academy, and would serve as the Seminary’s first Principal. The only non-clergyman in the group was Samuel’s younger brother John Payson Williston (see Firebrand). These men would become the core of Williston Seminary’s first Board of Trustees.

There was much to be done — indeed, it seems remarkable that ground would be broken for the first seminary building the following June 17, and that classes would meet in December. But consistent with their times, Williston and friends believed in action, sometimes at the expense of deliberation. Thus, it should perhaps be no surprise that Samuel Williston, who had strong feelings about education, took his time putting his thoughts to paper. But it needed to be done. Samuel expected his vision to provide direction to the Board and, as shall be seen, not only during his lifetime. A statement of mission was required. It took three years, but in 1845 Samuel Williston published The Constitution of Williston Seminary. Continue reading