From the Archivist’s Bookshelf

In the half-century prior to the Civil War, antislavery sentiment was strong up and down the Connecticut Valley. Yet there was an essential conflict between two schools of Abolitionists: the high-minded movement inspired by reformer and The Liberator editor William Lloyd Garrison (1805-1879), and a number of rabble-rousers who advocated more direct action.

In the half-century prior to the Civil War, antislavery sentiment was strong up and down the Connecticut Valley. Yet there was an essential conflict between two schools of Abolitionists: the high-minded movement inspired by reformer and The Liberator editor William Lloyd Garrison (1805-1879), and a number of rabble-rousers who advocated more direct action.

Five of the latter, all residing in Northampton, are treated in a new book by Bruce Laurie, Rebels in Paradise: Sketches of Northampton Abolitionists (Amherst: The University of Massachusetts Press, 2015). Dr. Laurie (Professor Emeritus of History, UMass Amherst) has selected the scholarly Sylvester Judd, African-American Underground Railroad conductor David Ruggles, newspaper editor Henry S. Gere, and preacher-turned-entrepreneur Erastus Hopkins. Not least among them was Samuel Williston’s brother, manufacturer John Payson Williston. All were local business, religious, and political leaders; none was especially subtle in advocacy of favorite causes, be they temperance, political reform, or the abolition of slavery.

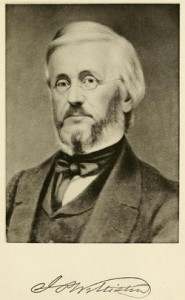

Like his elder brother Samuel, John Payson Williston (1803-1872) broke with several generations of Williston male tradition by choosing a manufacturing career over the Congregational ministry. Again similar to Samuel’s experience, the decision was driven by circumstance: neither was able to complete a university education because of poor eyesight. From there, their paths diverged. Samuel, largely through prescient investment, became one of Western Massachusetts’ leading industrial barons and philanthropists, but one whose public advocacy of reformist concerns, however passionately he believed in them, was often held in check by a need to protect his Southern business interests and, perhaps, the desire to project a certain patrician reticence.

John Payson, having never risen higher than “upper middle class,” and in any case, constitutionally immune to most class-consciousness, felt no such need to hold back. Indeed, his enthusiasm for favorite causes would ultimately prove divisive. While his supporters loved “Deacon” Williston, he brought out the worst in his opponents. Twice, in 1848 and 1853, he was the victim of arson, in the second instance narrowly escaping with his and his family’s lives. Who set the fires was never agreed upon: John Payson had bitter enemies in the anti-abolition and anti-temperance movements alike. The reality was, in Dr. Laurie’s words, that “Whatever the motives of his enemies, the fact remains that Williston abhorred liquor—and slavery—and equated them. He saw the use of alcohol as a form of enslavement, a more ominous and immediate scourge because it went on in his own backyard.” By the 1840s, Williston’s temperance passions had evolved to a demand for outright prohibition, a turn that “sharply divided the town and set the antislavery movement against itself.” [p. 63]

He presented an unusual model for a political radical. Short-sighted and suffering from speech difficulties, he was not a great reader or writer, and avoided speaking in public. His entrepreneurial successes included the invention of an indelible ink for marking laundry, and the establishment of a Florence silk mill. While he lived comfortably, he deplored ostentation (in sharp contrast to his Easthampton brother). He gave much of his income away, not only to radical causes, but to his church, education, and to the improvement of the lives of his workers. But he was also a conductor on the Underground Railroad. He appears to have gone out of his way to hire black workers and even adopted an African-American child, “a defiant rebuke to the racial decorum of the day.” [p. 74]

John Payson Williston was a challenging man, among others equally difficult. And Bruce Laurie is a born storyteller who presents Williston and his fractious colleagues with a wonderful sense of detail, while tying them to the larger social and political phenomena of pre-Civil War America. Professional historians will enjoy his impeccable scholarship; “lay” readers will be intrigued and entertained. Rebels in Paradise is recommended to anyone with an interest in local history, abolition, or in the hurlyburly of antebellum American politics.

John Payson Williston was a challenging man, among others equally difficult. And Bruce Laurie is a born storyteller who presents Williston and his fractious colleagues with a wonderful sense of detail, while tying them to the larger social and political phenomena of pre-Civil War America. Professional historians will enjoy his impeccable scholarship; “lay” readers will be intrigued and entertained. Rebels in Paradise is recommended to anyone with an interest in local history, abolition, or in the hurlyburly of antebellum American politics.