Guest blogger Peter Valine has taught history and social science at Williston Northampton since 1998, and was appointed Dean of the Faculty in 2010. He presented the following at the opening-of-school faculty meeting on August 30, 2012.

Guest blogger Peter Valine has taught history and social science at Williston Northampton since 1998, and was appointed Dean of the Faculty in 2010. He presented the following at the opening-of-school faculty meeting on August 30, 2012.

Thinking about how to start the year, I wanted an opening that was inspirational — something to fuel and direct the positive energy of this moment. I wanted an opening that would engage us — and hold our interest. I wanted an opening with an underlying message — that gave context and meaning to our gathering together at the beginning of the year. In thinking about how to accomplish these aims (inspiration, engagement, and an underlying message), I came to the realization that I needed to tell a story.

I’ll be honest, I wanted to start the year with an Olympic story — a Williston Olympian who through purpose, passion, and integrity rose to the ranks of an Olympic medal winner — but my research revealed that the Olympic legacy of Williston athletes is actually quite modest. So I went to the Archives for inspiration, and was led to the life of Charles Fred. White, whose story serves my purposes perhaps even better than a Williston athlete who gained Olympic fame and glory.

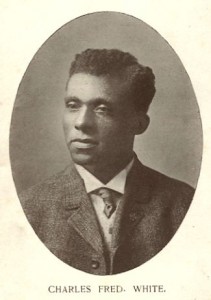

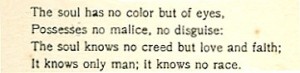

Charles White was a member of the Williston Seminary class of 1909. He was a patriot who loved his country but he was not always loved by his fellow countrymen. He was an accomplished poet whose lyrics provide important insights into the nature of American society at the turn of the century. He was a veteran of the Spanish-American War who served with a combat regiment in Cuba. He was a graduate of the University of Pennsylvania Law School, who enjoyed both financial and political success in the city of Philadelphia. He was a well-known radio concert singer, and at least according to one account I read he equaled the world record for the 50 yard dash at 5.2 seconds. Charles White was also an inventor who, according to an article in a Philadelphia newspaper, used an electric battery wired to an old hand stop watch to discover a more accurate method of timing track events. So this is a story about a War veteran, scholar, poet, singer, athlete, and inventor; Charles White was a true Renaissance Man and a man respected by contemporaries for his versatility and talent.

I will use some of the poetic words of Charles White to help narrate his story, and I hope that this story serves as an inspiration to us as we open this new school year.

The story starts in Tennessee in the year 1876 with the birth of Charles Fred. White to parents who had been slaves. Charles would be the oldest of 10 children. When Charles was very young his family moved to Springfield, Illinois. Charles provides an autobiographical sketch of his earliest days in the poem “A Tale of a Youth of Brown,” that he wrote while at Williston.

Out from the plains of Illinois,

Out from the town of Lincoln’s home,

Where the emancipator’s tomb

Answers the stare of State House dome,

Came forth a strippling of a boy.

Brown as a chestnut was his face,

Brown as two beans his soulful eyes,

Curly his hair like waves and black.

Bright was his face as summer skies:

He was of Afric’s sunburnt race.

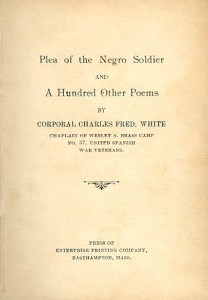

(Charles Fred White, Plea of the Negro Soldier and a Hundred Other Poems. Easthampton: Press of Enterprise Printing Company, 1908.)

In the few sources that inform us about Charles White’s adolescence a major theme from this period is an education denied. His father forced him to leave school at age 15 to get employment to support the family. As a result of this development — perhaps in an act of rebellion — he struck out on his own and struggled to support himself. We can see the passion for education and the burning desire to learn in subsequent stanzas of “A Tale of a Youth of Brown.”

He was denied his chief desire,

Taken from school, fore’er perhap,

But he, undaunted by his fate,

Ran away from his mother’s lap;

Left to escape his father’s ire.

To the great city came this lad,

As yet unskilled in worldly lore,

Sought out employment for himself.

During his leisure he would pore

Over some book, some song he had.

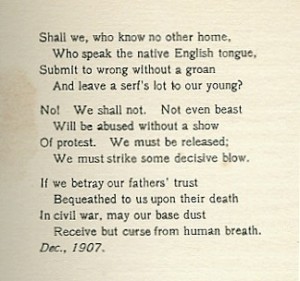

In his early 20’s, struggling to provide for himself, Charles White enlisted in the Eighth Illinois, an all-Black regiment that served in Cuba during the Spanish-American War. During the war he served as a sergeant major, a chaplain’s assistant, and a regimental clerk. His poetry written during the war clearly showed that he was ready to fight and die for the cause of freedom for the Cuban people. He wrote, for example, that “if I died upon the battleground, with unfurled glory all around, then I am fully content to die, and be upraised to him on high.” His unit saw combat in Cuba and he wrote about the burial of 20 members of his unit who died from combat or disease.

After returning from the war in 1899, he became very disillusioned with his experiences back in the U.S. He was angry about the hypocrisy of fighting for freedom abroad and returning home to a land in which he was not free. In his poem “The Negro Volunteer,” he writes:

He volunteered his life and health

To go to cruel war—

Increasing thus his country’s wealth

In soldier boys afar—

To fight the battles of a land

which does not him protect.

He experienced refusals to serve him meals in Denver restaurants, he suffered Jim Crow discrimination in Little Rock, Arkansas, he was threatened with lynching in Missouri and, as he writes, was “proscribed, ostracized, and mistreated” at many places in the North. However, he still had a burning desire to learn, and in 1903, finally caught a break.

Finally heard he of a school

Where he might work and in return

Receive the knowledge which he wished.

Famed was this school throughout the land

Even from o’er the seas there came

Youth to be educated, trained,

Not only in the paths of fame.

But in base hatred, man for man.

The famed school was Exeter. Charles White went there for a time, but was ultimately expelled due to southern whites at the school who objected to his presence on the campus. He went briefly to Boston Latin. Then Joseph Sawyer, Headmaster of Williston Seminary, invited him to join this community, where he enrolled in 1906 as a 30-year-old African-American combat veteran in a mostly white sophomore class.

Sad, but resolved, he left its walls,

Went to a more congenial one

Where he might have a right to live;

He found this right at Williston;

Found justice, freedom in her halls.

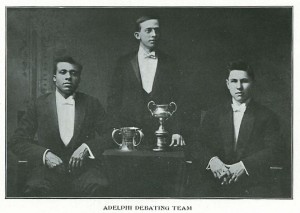

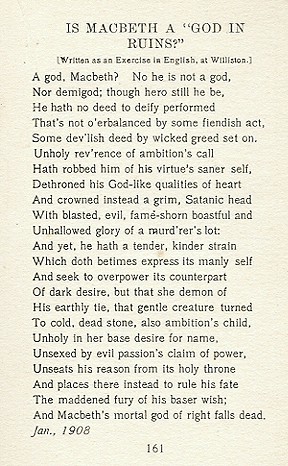

In his days at Williston, Charles White maintained high grades, excelled in track and on the Adelphi Society’s Debating Team, sang and played his guitar in musical ensembles. He continued to write poetry — many of his poems were published in The Willistonian — and to work at Enterprise Printing in the town in Easthampton. Enterprise published White’s Plea of the Negro Soldier in 1908; White probably set the type himself. There is a spirited poem he wrote entitled “Williston Battle Song” that describes a football game between Williston and Worcester, in which he wrote that “after the battle was o’er, Worcester went home worn and sore; Williston cheered for the Blue and Gold, While the chapel bell tolled.”

The closing stanza of “The Tale of a Youth of Brown” states,

Found friendly spirit in her town;

Found helping hands and willing hearts

Brightened, his soul poured forth its strains,

Pleasing the townsfolk with his arts

Until they loved this youth of brown.

I wanted to share Charles White’s story with you this morning, in part because I find it so uplifting. The obstacles that Charles White faced in his life, whether they were poverty, injustice, war in a foreign land, or racism at home, could not contain him. It is a story about perseverance, determination, and in the end it is a story of success.

It’s interesting that after leaving Williston there is not much record of Charles White writing more poetry. Perhaps he is like many writers and artists whose most creative periods were periods of angst. Once he had achieved success his need to write and his creativity declined. Or perhaps, as one researcher wrote, his later work is still waiting to be discovered in an attic somewhere in Philadelphia. (Roger J. Bresnahan, “Charles Fred White: a Forgotten Black Poet.” Negro History Bulletin 40 (1977), p. 661.)

Another reason I wanted to share Charles White’s story is just to put in a plug for storytelling as a vehicle for learning. Stories often provide the structure through which we learn and remember. Many of us, for example, have effectively learned cultural and  religious values through reading and listening to stories. Daniel Pink, in his book A Whole New Mind, notes that “Stories provide us the ability to place facts in context and to deliver them with emotional impact.” (New York: Riverhead, 2005; p. 103) Pink uses a quote from cognitive scientist Roger Schank, that “Humans are not ideally set up to understand logic; they are ideally set up to understand stories.” (Pink, p. 102) If we can wrap some of the facts, theories, or concepts into context through an engaging story, then I think this information will resonate and have more staying power. I think many of us have seen the powerful informational and emotional punch that stories can deliver when members of our community have shared their personal histories.

religious values through reading and listening to stories. Daniel Pink, in his book A Whole New Mind, notes that “Stories provide us the ability to place facts in context and to deliver them with emotional impact.” (New York: Riverhead, 2005; p. 103) Pink uses a quote from cognitive scientist Roger Schank, that “Humans are not ideally set up to understand logic; they are ideally set up to understand stories.” (Pink, p. 102) If we can wrap some of the facts, theories, or concepts into context through an engaging story, then I think this information will resonate and have more staying power. I think many of us have seen the powerful informational and emotional punch that stories can deliver when members of our community have shared their personal histories.

Finally, I wanted to start with this story because I believe it illuminates and reminds us of the core values of our community and our institutional goals.

Charles White’s life story models a passion for learning and quest for academic excellence that lies at the heart of our community’s mission.

I don’t think it is surprising to many of us that Williston proved to be “the more congenial place” where Charles White “found helping hands and willing hearts.” I remember back when we were doing our mission statement, brainstorming almost exactly a century after Charles White, and we perceived that one of our community strengths was that we continue to be an unpretentious and welcoming community of adults and students. It is not surprising that it was here that the people “came to love that youth of brown.”

Charles White’s story is a tribute to the integrity of Joseph Sawyer and certainly is an early example of a community commitment to diversity in an era where this commitment was not the norm. Charles White dedicated a poem to Joseph Sawyer entitled “To Williston at Parting” where he thanked Williston for the “countless debt I owe” to Headmaster Sawyer and the school who spoke words of cheer and encouragement to him.

As we start the year, I am confident that we will all do our best to provide an environment like the one here in the early 1900’s that brightened Charles White and allowed his soul to pour forth its strains.

I hope that over the course of the year we can spend some time identifying and telling school stories like the story of Charles White; stories past and present that illuminate who we are, how we fit in, and why that matters. Stories to tell ourselves, to guide and inspire us, and stories to tell those outside our community that will distinguish us.

I would like to close with two short pieces. First, the last poem in Charles White’s book is called “Our Aim in Life”.

We should all endeavor to make others happy,

For life of itself enough sorrow will give:

Our sympathy, happiness, love, all have value—

The world should be better because we have lived.

It is a poem that he wrote while a student at Williston.

Finally, a Native American proverb:

Tell me a fact and I will learn; tell me the truth and I will believe; but tell me a story and it will live in my heart forever.

Your comments and questions are encouraged! Please use the space below.

Charles Fred White was my great-great-grandfather, where did you do your research for the information you’ve written about him?

Mr. Valine derived most of his narrative from Charles White’s own writings, primarily collected in his book, The Plea of the Negro Soldier. In addition, he had access to Meline Kasparian, “Charles Fred White: an Early Black Poet,” Masters thesis, University of Massachusetts, 1972; and Bresnahan, Roger J., “Charles Fred White: a Forgotten Black Poet,” Negro History Bulletin, 40 (1977), p. 659-661. Photocopies of both are in the Williston Northampton Archives.