The silver robot bumped gently against a wall, reversed, and then ran over a blue racquet ball, where it lodged, rocking slightly. Chris Berghoff sighed.

The silver robot bumped gently against a wall, reversed, and then ran over a blue racquet ball, where it lodged, rocking slightly. Chris Berghoff sighed.

“If it really shuts down when it hits one of the balls, and there’s going to be 100 of them, I’m pretty sure that’s a problem,” he said to his teammates, who were typing at computers around the room.

“Come along, robot,” Berghoff said, plucking the machine off the ground and carrying it into a workroom. A hacksaw could soon be heard grinding away.

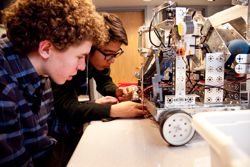

None of the team members appeared very concerned by this. When you’re preparing for a state-level robotics competition like FIRST Tech Challenge, there’s a lot of tinkering involved.

See a full gallery of the team at work.

In fact, since September when they started building their robot, the six  members of the robotics club—Berghoff ‘14, Matt Cavanaugh ‘14, Nick Dalzell ’15, Ethan Kimball ‘14, Kelby Reid ‘15, Kyle Watson ‘15, and Sean Won ‘14—have done almost nothing but problem solve.

members of the robotics club—Berghoff ‘14, Matt Cavanaugh ‘14, Nick Dalzell ’15, Ethan Kimball ‘14, Kelby Reid ‘15, Kyle Watson ‘15, and Sean Won ‘14—have done almost nothing but problem solve.

The first step was coming up with a design for the challenge. In “Bowled Over,” the game that they’ll be tested on during the Northern New England FTC Championship in Antrim, NH on March 10, two teams work together to score points in various ways (including moving and stacking crates, raquet balls, and bowling balls).

The 25 teams at the challenge will be vying for two qualifying positions to represent Northern New England at the FTC World Championships in Atlanta, Georgia in April.

Watch the FIRST Tech Challenge video on the competition.

Out of 100 racquet balls on the field, most are worth one point—except for 25 balls with magnets hidden inside, which are each worth 25 points when placed inside a goal. If the robot can move one-point balls into goals and crates, then they earn more points. Most teams have tackled this by adding a bucket that the robot lifts, or a plow to move them around.

Out of 100 racquet balls on the field, most are worth one point—except for 25 balls with magnets hidden inside, which are each worth 25 points when placed inside a goal. If the robot can move one-point balls into goals and crates, then they earn more points. Most teams have tackled this by adding a bucket that the robot lifts, or a plow to move them around.

The Williston robot, dubbed “Derek,” sorts through the balls by picking them up with a conveyor belt, checking them and keeping the more valuable magnetic ones.

“We’re going to be one of the few robots that collects magnetic balls,” said Matt Cavanaugh, who divides leadership duties with Sean Won. “I think that’s going to be rare because it’s hard to do.”

Won, like the rest of the team, thinks that the particular complexity of the Williston robot will put it ahead of the competition. Still, he admits there is quite a bit of work still to be done, including stress testing to make sure that the robot can crash into walls or other objects and keep going.

“We’re excited, but I’m kind of nervous too,” Won said.

“No faith in me, Sean?” called Kyle Watson, who was programming in one corner and who will be one of the robot drivers during the competition.

“—but I think our team is going to win because there’s Kyle, of course,” continued Won without missing a beat.

The club, in its fourth year, has competed in the FIRST competition three times. Last year, the club was turned into a winter sports alternative, which allows the six members to meet four times a week for up to 2.5 hours a day during the trimester. During the spring and fall, the club meets once a week for 45 minutes.

“I wanted to find a fun way to get students involved in mental athletics, but on a deeper level,” said math teacher and academic computing coordinator Ted Matthias, who advises the group and pushed for sports status.

During the year, Matthias teaches foundational elements in programming, robotics, and advanced placement computer science—the coding gauntlet from beginners to the theoretical-level computer theory. It’s while working with robots, though, that the students learn how to work in three dimensions, Matthias said.

“Because they’re dealing with an object, a robot, they don’t personalize their mistakes as much as they do with a computer,” Matthias said. “They say, ‘Oh, my computer’s misbehaving’ when really it’s the code that’s wrong. It’s a non-threatening way to make mistakes.”

A club like robotics is not a cheap one. Members must begin fundraising in the spring. Last year, they raised $600 by selling Wildcat Packs during assessments. Of that, $325 went to various competition entry fees and the rest bought parts for the robot.

Matthias said the team is now looking for sponsors and other potential partnerships, such as with an engineering company in the valley or another closely aligned business.

Back in the classroom, the team had the robot going again, but a bolt had fallen off the chassis. Won began fiddling with the conveyor belt, which was still catching on one side. Despite these minor hitches, Cavanaugh said he was confident of the robot’s abilities.

“I think it’s going to work exactly how we want it to,” he said. “Whether we win or not with that, I don’t know, but I think we’re going to get exactly what we want to get out of it.”

And what does the team want out of their machine?

“That it works properly,” Cavanaugh said. “And we get a lot of points.”