Note: For Part I of this article, please see The First Chinese Students at Williston.

The closing of the Chinese Educational Mission and the recall of its students to China in 1881 ended Chinese attendance at Williston Seminary for the next twenty-three years. There were several factors, not the least of which may have been that Williston’s Principals, Joseph W. Fairbanks (served 1878-1884) and William Gallagher (served 1886-1896) had little interest in maintaining international diversity. There were significant enrollments of international students (by whom we mean citizens of other countries, not American dependents of diplomats, businessmen, or missionaries) from Latin America, notably Cuba and Panama. That is perhaps not surprising, since the United States had significant political and business interests there. But with the notable exception of Williston’s first two Siamese (Thai) students, Nai Kawn, class of 1884, and Boon Itt, 1885, there was practically no attendance from any Asian countries.

The anti-Chinese atmosphere in the United States of the 1880s was certainly a factor. (Since bigotry prefers generalities, for the most part it was extended to all Asians.) So, too, were the practicalities of travel. Cross-country rail travel had improved mightily since the completion of the first route in 1869 (ironically, built largely with Chinese labor), but even with the rise of steamships and without the need for a dangerous and lengthy voyage around Cape Horn, passage from Asia was measured in weeks.

But American attitudes were also changing. Despite the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which severely restricted immigration, Chinese neighborhoods – “Chinatowns” – were springing up in many larger cities, and not just on the West Coast. Inevitably, the country was becoming more tolerant, although shamefully, the Exclusion Act was not repealed until 1943.

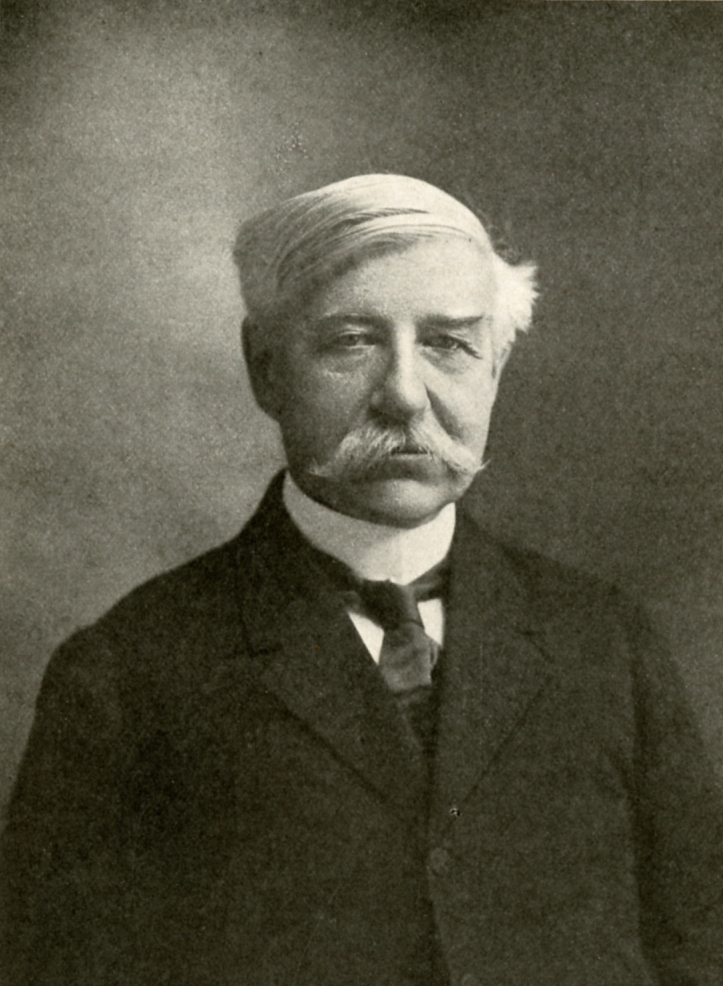

At Williston, Principal Gallagher stepped down in 1896, and was succeeded by Joseph Sawyer. Sawyer, whose biography has been treated in detail in these pages (see “Visionary Keeper of the Flame“), had a genuine, personal interest in Chinese students, having encouraged the Chinese Educational Mission students’ Christian conversion and published on the subject. When a trickle of Chinese applicants began to appear, he jumped at the chance to welcome them. As a group, the first enrollees were not an immediate success.

(A note on names: since we do not have modern Pinyin transliterations for any of the early 20th century Chinese students, their names are here rendered as they appeared in school records, using the older Wade-Giles anglicizations. American practice puts the patronymic (family name) last, although in Chinese, it is properly placed at the beginning of a name. Thus, Chin Chao Kwong, whom we are about to meet, would have signed his name “Kwong Chin Chao.” If the modern reader finds this confusing, it puts him on similar footing with Williston’s record-keepers of a century ago, who sometimes confused family and personal names.)

The first Chinese national to enroll was Chin Chao Kwong, who arrived in September, 1904. Kwong was the nephew of Kuang Guoguang, an original Chinese Educational Mission (henceforth CEM) student who had attended Phillips Exeter in 1880-81. In 1904 Kuang was a diplomat in Washington. He brought his son and nephews to visit his former host family, Hervey and Nancy Dickerman, in Holyoke, Mass. [Edward J. M. Rhoads, Stepping Forth Into the World: The Chinese Educational Mission to the United States, 1872-81, Hong Kong University Press, 2011, 100, 211] A Mrs. M. L. Dickerman of Holyoke, apparently related to that family, offered to sponsor Chin Chao Kwong at Williston. Kwong was from Tsinanfu, today called Jinan, in central China’s Shandong Province. He started as a member of the class of 1907, but his initial grades were abysmal. He stepped back to the class of 1908, but it didn’t help. After a stay of three years, he left without graduating at the end of 1907. In 1920 Mrs. Dickerman informed the school that Kwong was in the head office of his father’s mining company in Jinan. After that we lose track of him.

Another student, Burbank Parn Yung, class of 1909, enrolled in Williston’s equivalent of the 9th grade in 1905, via a CEM connection. A native of Guangzhou, he had either taken the name of. or was named for, his sponsor, Julia Burbank. Miss Burbank, of Hartford, Conn., had been one of the original CEM hosts in the 1870s, along with her widowed mother and unmarried sister [Rhoads, 71, 103]. How Parn Yung came to the United States is unknown. He also left Williston quickly, after only one trimester.

There were two other short-time students prior to 1909. Tai Che Quo, of Wuhan, Hubei, in central China, joined the junior middle (i.e., sophomore) class in 1907, but remained for only one year. His grades were decent, and his transcript does not give a reason for his not returning. While at Williston, his address was care of the Chinese Legation in Washington; perhaps he was a diplomatic dependent whose father returned home. Liang Ching Liu, of Ganzhou, Jiangxi, was a junior middler in September 1908, but enrolled in fewer than the normal number of classes, and left before the close of the winter term.

It was not an auspicious beginning. But everything would change with the arrival of the Boxer Indeminty Scholars of 1909-10.

The Boxer Rebellion and Indemnity

Throughout the 19th century, the United States, Japan, and several European powers had taken control of much of China’s economy and trade. Several military attempts by China to mitigate this, from the Opium Wars of 1839-42 and 1856-60, to the first Sino-Japanese War (1894-95) had only served to entrench foreign dominance even more.

In the late 1890s, an initially secret society popularly known as the “Boxers” – The Society of Righteous and Harmonious Fists – began to attack Western properties and Christian churches. The movement, which justifiably blamed poor conditions on foreign influence, coalesced and grew in popularity until 1900, when the Boxers invaded Beijing, attacking American and Chinese Christians and destroying churches, railroad stations, and other infrastructure. When, in June, they laid siege to Beijing’s diplomatic district, the Dowager Empress Cixi (1835-1908, the de facto ruler of China during the reign of its final Emperor, Guangxu, 1871-1908) declared war on all foreign nations with interests in China.

The response was swift and brutal. Ultimately a military coalition comprising the United States, Britain, Japan, Russia, Austria-Hungary, Germany, France, and Italy prevailed, but only after many weeks of bloodshed on both sides. The treaty that ended the war, the Boxer Protocol of 1901, left China worse off than before, with restrictions on domestic military activity and a requirement that China pay $330 million in reparations – approximately $10.1 billion in 2021 dollars. This was the so-called “Boxer Indemnity.”

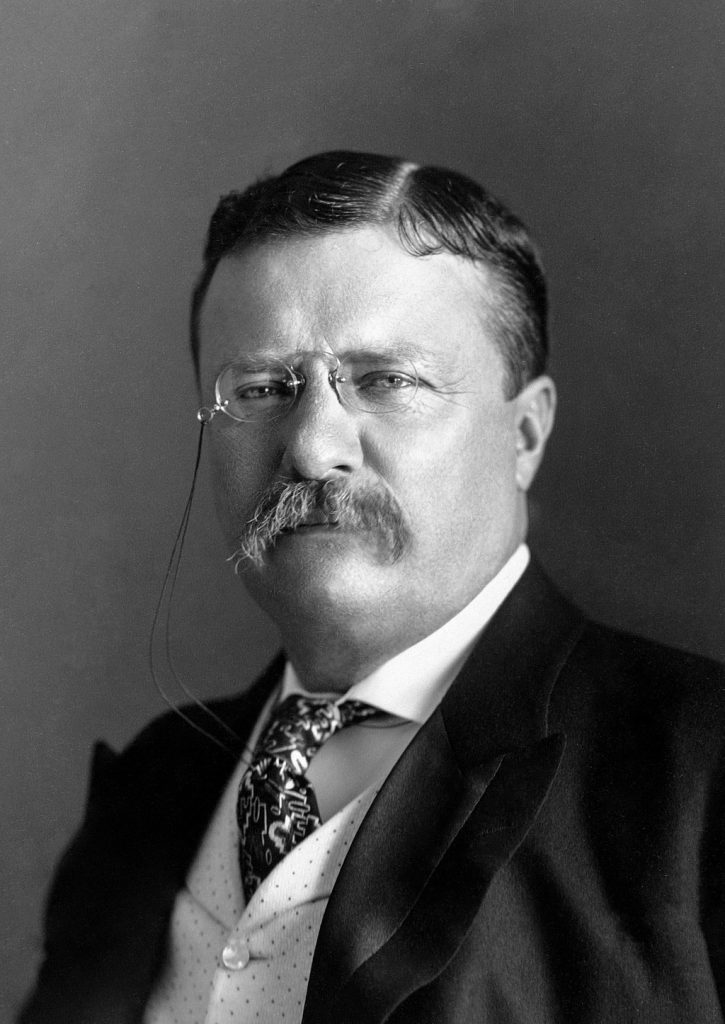

In 1908, largely through the efforts of Chinese Ambassador Liang Cheng, President Theodore Roosevelt was persuaded to return nearly $12,000,000 of the U.S. share of the indemnity to China, to be used for education. There were several factors in favor of this: one was that a growing sense of Chinese nationalism, combined with resentment over the terms of the Protocol and the treatment of Chinese immigrants in the United States, resulted in a 1904 Chinese boycott of American imports. This had a disastrous effect on American textile and other industries. But Roosevelt and his British counterparts also realized that far more could be gained in the long term by engaging with the Chinese, rather than exacerbating the punitive approach taken by the other powers.

The United States funds were to be used for two purposes. The first was the 1911 founding of Tsinghua University in Beijing. Today it is among the most prestigious of China’s universities. The second was the creation of the Boxer Indemnity Scholarship, which would send groups of Chinese students to study in U.S. universities. Administrative offices were established in Shanghai, a program of competitive examinations was undertaken, and in 1910, the first wave of Boxer Indemnity Scholars embarked for the United States.

The Boxer Indemnity Scholars at Williston

It was probably inevitable that some of the Chinese students would attend Williston Seminary. While in the States, they were the responsibility of Ambassador Liang Cheng. Once again, the narrative circles back to the Chinese Educational Mission. Liang, formerly named Liang Pixu, had been among the fourth group of CEM students. Aged 12, he had lived in nearby Amherst, Mass., and eventually matriculated at Phillips Academy in Andover. He would certainly have been familiar with Williston.

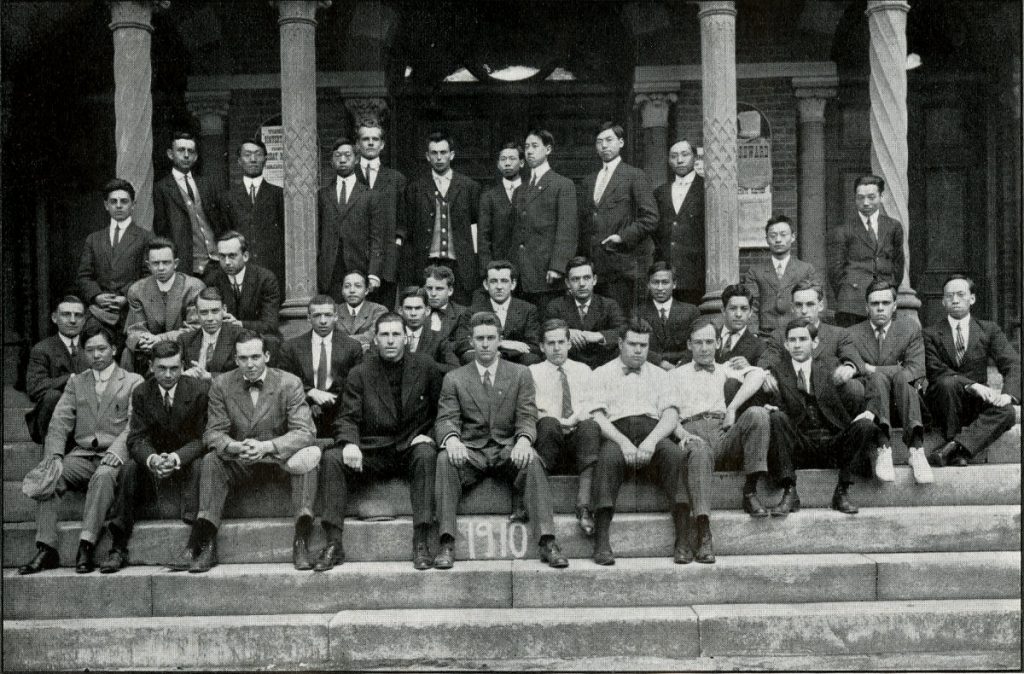

According to the account in the November 23, 1909 Willistonian, the first group of 100 students arrived in Washington on November 6, and traveled to Washington, D.C. Liang immediately took half of them north to Springfield, and set about enrolling them in regional schools. Based on the results of a placement exam, some went directly to colleges; others, it was determined, required further secondary school preparation. Ultimately, ten of the Scholars came to Williston:

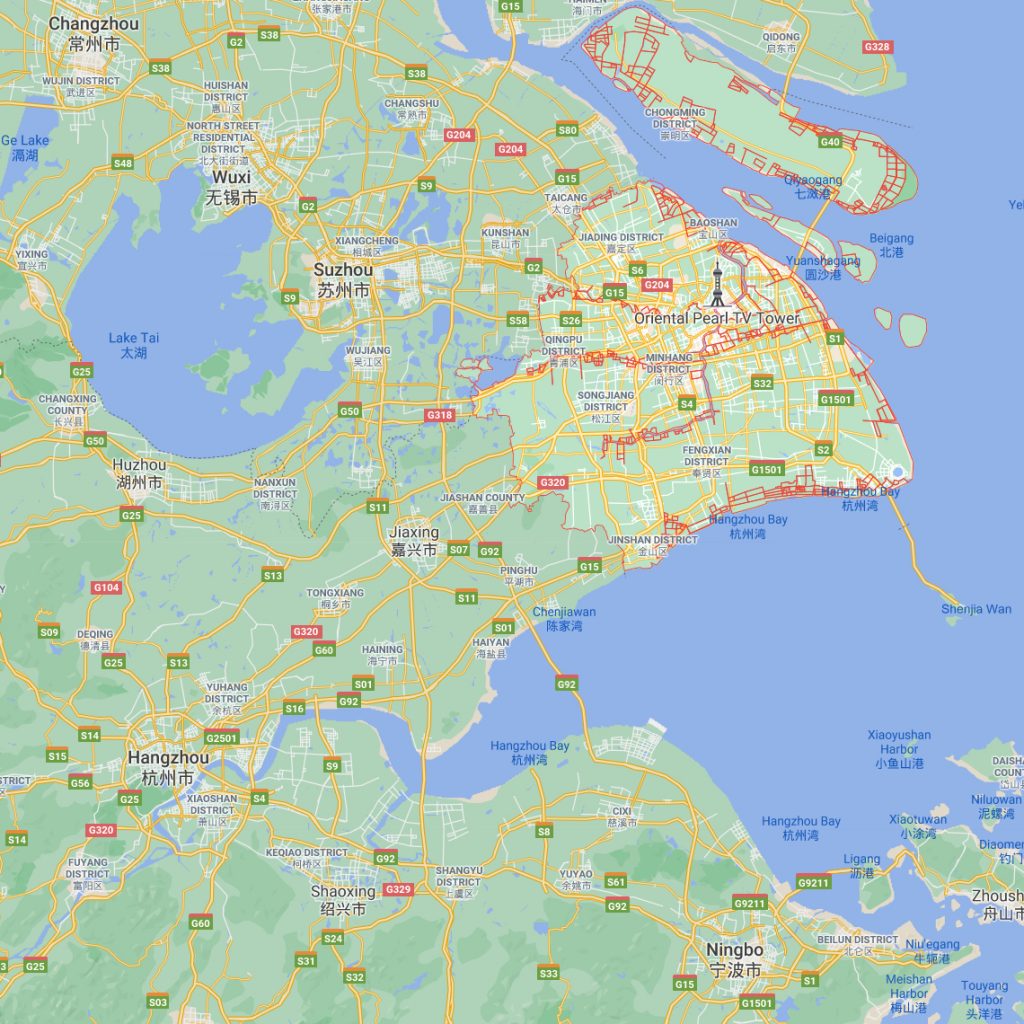

Chang Yuing Chiu, from Wuxi

Chimin Chu-Fuh, Nanxiang

Moo Ching Hou, Danyang

Chee Sing Hsin, Shaoxing

Hsü Pei (Paul) Hwang, Shanghai

Pan Cheng King [or Chin], Tianjin

Wai Gyiao Loo, Ningbo

Chen Fu Wang, Kunshan

Szi Ji Wang, Ningbo

Yu Lin Wu, Suzhou

In introducing them, the Willistonian reported enthusiastically, “The educational system in China is being revolutionized and there is need of men who understand life as it is in the Western world. The boys take a keen interest in all they see and hear and manifest a desire to learn more about the civilization which to all but two of them is entirely new . . . Williston Seminary is indeed fortunate in getting ten of these trained men. The fellows should do everything in their power to make these Chinese students feel at home.”

An additional student, Tsu Mai Yu, from Suzhou, would join the ten in January. Although he was affiliated with the Boxer Indemnity Scholars program, his family apparently paid his way.

Those familiar with Chinese geography will note that all but one of the students lived in urban centers within a day’s journey of Shanghai, where the Boxer Indemnity Scholars headquarters had been established. The exception was Pan Cheng King, whose father was a government official in Tianjin, near Beijing in the north.

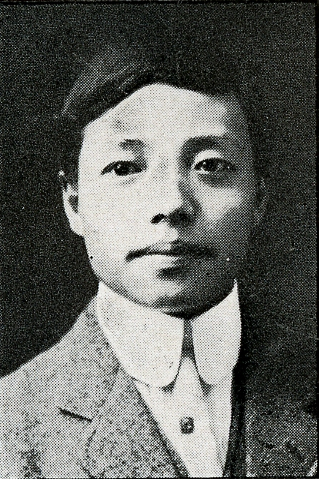

We don’t always know dates of birth, but from those we have, it is clear that the range of ages was broad, from Chen Fu Wang, 17, to 28-year-old Chimin Chu-Fuh. Each student’s transcript names his previous school. Most had attended “colleges.” Our original assumption was that the word was used in the British sense – secondary schools, like Eton College. But Chang Yuing Chiu’s transcript clearly reads, “A.B., Soochow College,” and four other Students had degrees from the Imperial Technical College in Shanghai.

Yu Lin Wu’s record includes his Imperial Technical College courses: Analytic Geometry, Higher Algebra, “Qualitative Analysis” – this is probably calculus, Physics Laboratory, Geology,, Elementary Mechanical Drawing, Mechanics, Elementary Electrical Laboratory, Electrical Engineering, Theory of Electricity and Magnetism, French, and English. A challenging curriculum; if this was typical, then the Scholars were very well prepared indeed. One wonders how they responded to being returned to high school.

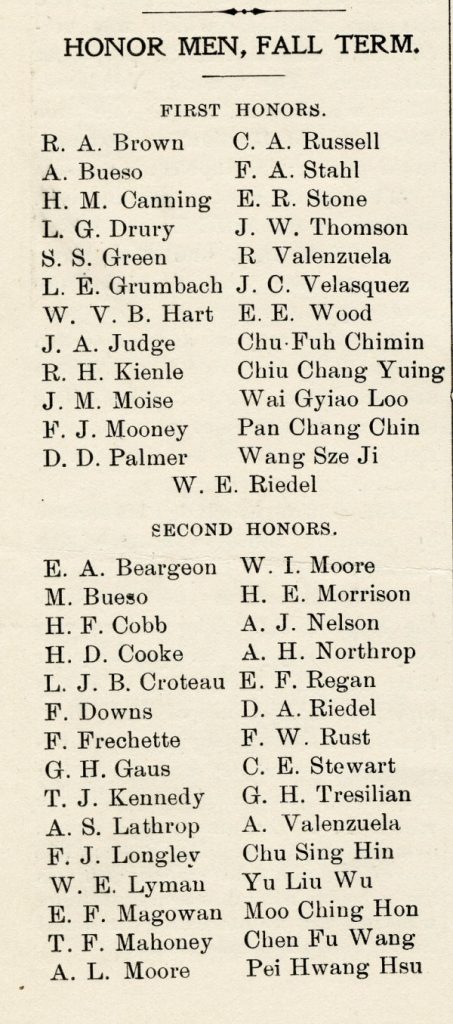

Even though the fall term was half over, the new students plunged right in. The following February, when the academic honors list for the fall term was published, every one of them was on it. So much for a gradual orientation. The students’ course selections drew from across the curriculum, with an unsurprising emphasis on the sciences: Mental Science (Psychology) and Natural Science were popular, as were various levels of Mathematics, Drawing, and Bookkeeping. Many took German, then considered essential for advanced work in the sciences; fewer, French. Everyone studied English and Composition.

We do not know whether any of the Chinese were already admitted to college, or whether they went through an application process while at Williston. Liang Cheng was undoubtedly working on their behalf. At this time, too, admission to the most competitive or prestigious schools was highly influenced by letters of support from the Headmaster. Sawyer would have been particularly enthusiastic. In any case, five of the eleven would attend the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (Moo Ching Hou, Chee Sing Hsin, Hsü Pei Hwang, Wai Gyiao Loo, and Yu Lin Wu); two Harvard (Chen Fu Wang and Szi Ji Wang), and two Cornell (Pan Cheng King and Tsu Mai Yu). Chimin Chu-Fuh went to Lehigh; Chang Yuing Chiu, the University of Wisconsin.

Debate

Records in the 1910 yearbook, The Log, suggest that for the most part, the Chinese students did not participate much in the school’s many teams and clubs. They did, however, form a Chinese Students’ Club. The Log’s description reads, “The Club holds weekly meetings to keep themselves proficient in speaking English as well as possible, and to secure better friendship between their members. The members of the Club have frequent intercourse with their countrymen in Amherst, Wesleyan, and other neighboring institutions. They have allied themselves with the American Association of Chinese Students.” One suspects that the Club actually served as a refuge where, rather than practice English, members could let their hair down and share Chinese language and culture.

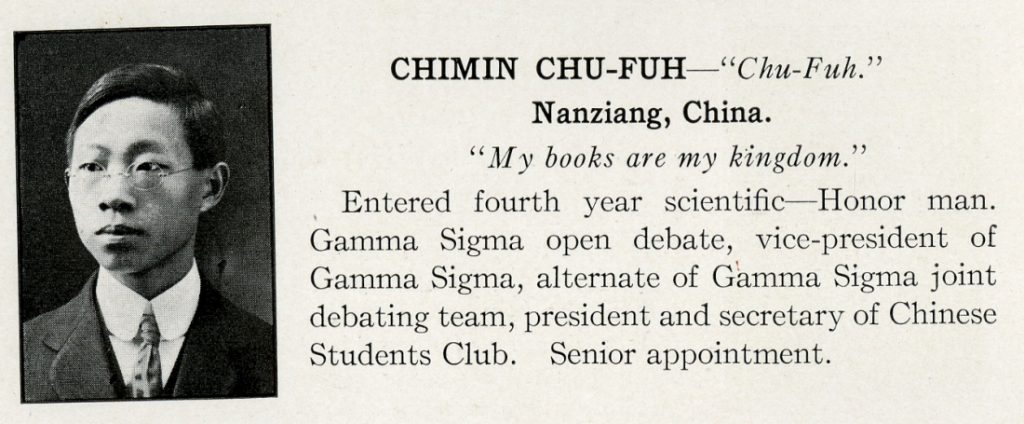

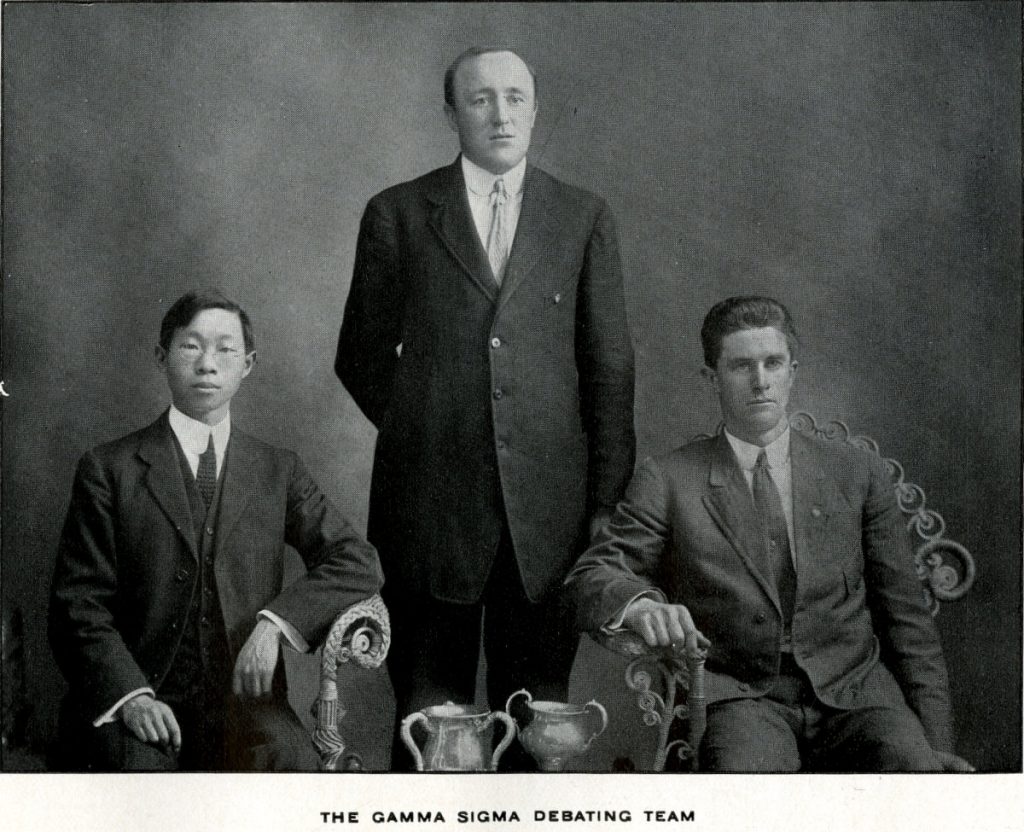

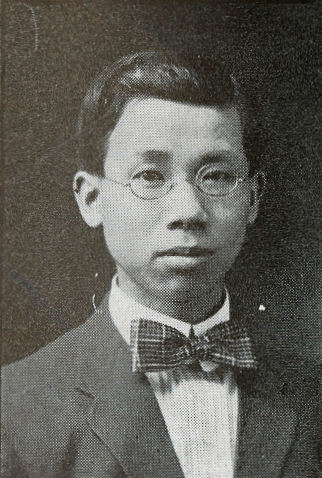

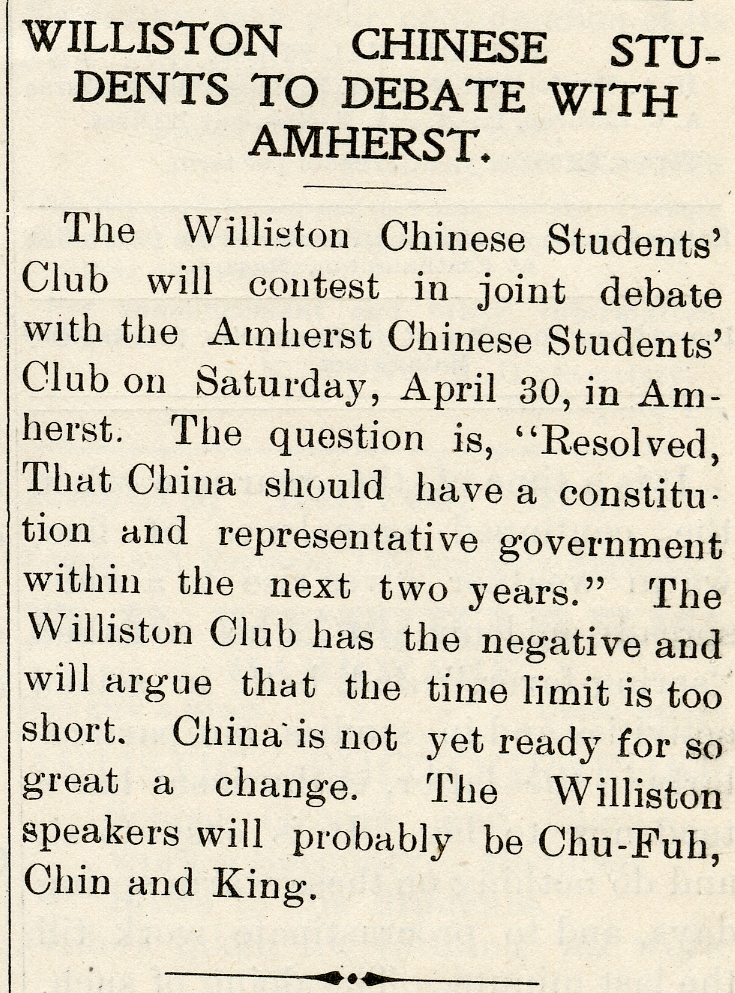

One student broke the mold. Chimin Chu-Fuh joined the Gamma Sigma debating society. Debate was a long-established Williston tradition. Campus debates were public entertainments, drawing large audiences from the school and the town, and were covered in The Willistonian with detail comparable to that which the paper lavished on football. Chu-Fuh made his first appearance on the podium in January, 1910, the first of three speakers arguing the negative, in “Resolved, that the United States would be benefited by a Ship Subsidy Law.” (One wonders how Gamma Sigma’s officers selected their often appallingly dry topics!) The negative side prevailed. The Willistonian’s reporter rather grudgingly asserted, “We admire the keen insight of Mr. Chu Fuh, and are pleased to say that sooner or later he will become a good debater.”

That was the last time the reporter attempted anything snide. Over the next months, he would admire Chu-Fuh’s grasp of data, his talent for refuting opponents’ arguments, and his “forceful” podium presence. Where the other two members of the team tended to rely on oratorical tricks and bombast, Chu-Fuh brought logic and analysis. By February, he had been appointed the alternate on Gamma Sigma’s debating team, but his theoretically inferior position most likely stemmed from his lack of seniority – he’d only been on campus for ten weeks. It is no accident that it is Chu-Fuh who appears in The Log’s photograph.

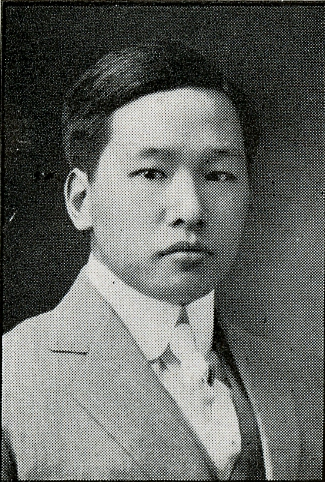

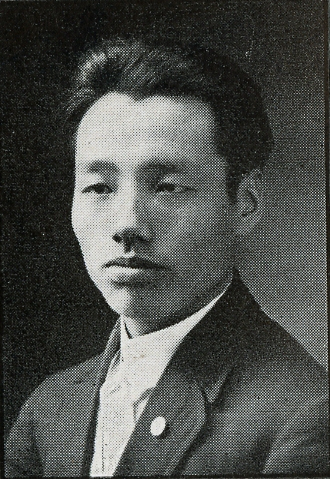

Pan Cheng King joined Adelphi, the rival debating club, although his exploits did not receive the same attention in the campus press. In April members of the Chinese Club traveled to Amherst College to debate “Resolved: that China should have a constitution and representative government within the next two years.” Chu-Fuh was joined at the lectern by King and Chang Yuing Chiu. They argued the negative, that (according to The Willistonian) acknowledged China’s aspirations, but “before undergoing such a change she should make the necessary preparations, such as extending education, taking the census, establishing local self-government . . . with the existing conditions in China, they cannot be completed within two years.” The affirmative prevailed, but both sides considered the event a success.

Graduation and After

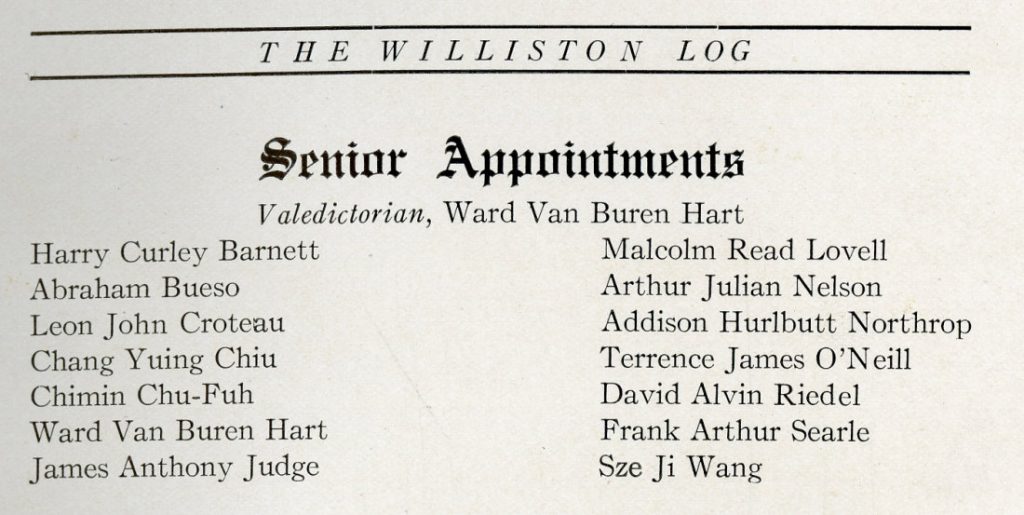

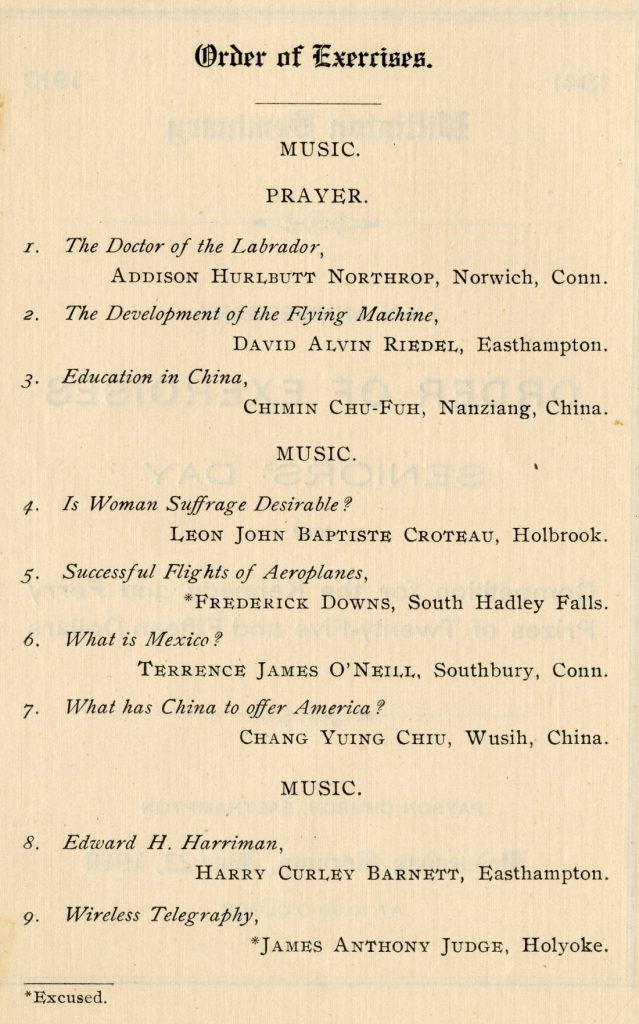

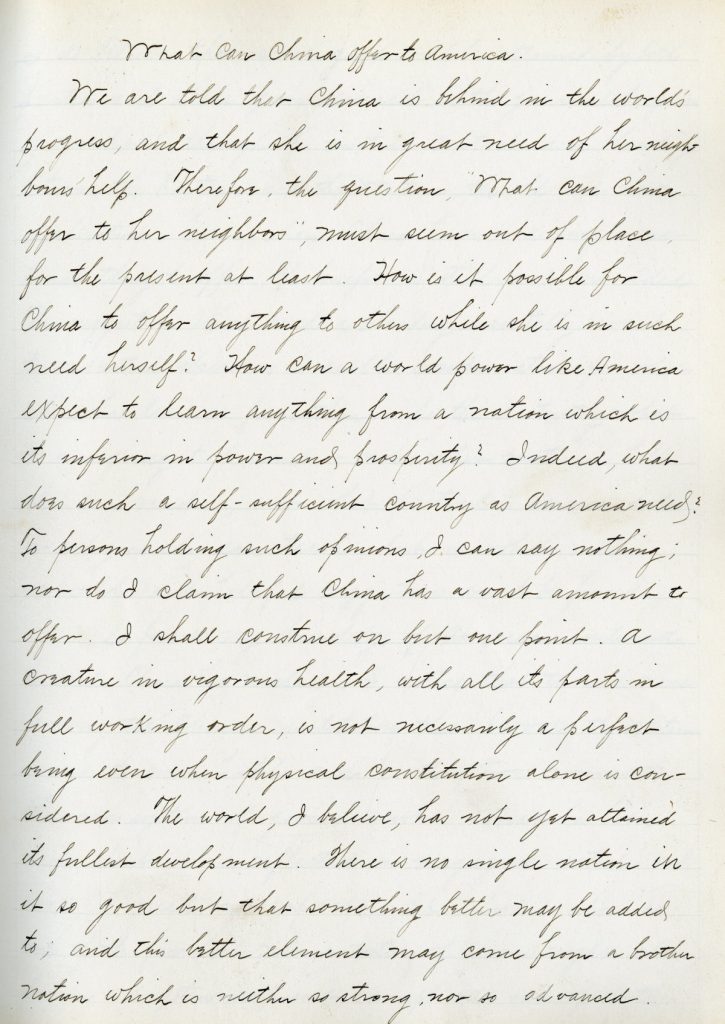

At this time in Williston history Commencement comprised several days of declamation and oratory exhibitions, culminating in a Seniors’ Day or “Annual Exhibition,” at which the best students in the class would address their fellows and guests. Among the highest honors Williston awarded were “Senior Appointments,” invitations from the Headmaster and faculty for students to read their original senior theses. Three of the coveted 15 appointments (in a class of 44) went to Chinese scholars: Chimin Chu-Fuh, who spoke on “Education in China”; Chang Yuing Chiu, “What Has China to Offer America?”; and Sze Ji Wang, “Why is English So Widely Spoken?” These papers survive in the Archives; they are well-argued presentations in idiomatic English. Chu-Fuh had even mastered the newly-invented typewriter. Chu-Fuh and Pan Cheng King were also among the eight seniors invited by the faculty to compete for the English Prize.

What became of the original eleven? The circumstances of history are such that we do not necessarily know. Pan Cheng King (Pinyin name, Jin Bangzheng) was a great success, in a way coming full circle: after earning degrees at Cornell and Lehigh, he returned to China as an educator. In 1922 he became President of Beijing’s Tsinghua University, founded as part of the Boxer Indemnity. He later went into the industrial glass business, and died in 1946.

Chimin Chu-Fuh was awarded sophomore status almost immediately after his arrival at Lehigh. Beyond his work in the School of Engineering, he excelled in oratory. In 1912 he won a prize for a speech on “The Present Revolution in China.” When last heard from, he was an engineer in Tianjin, but there is no record of his whereabouts after the 1930s.

While at Harvard, Sze Ji Wang “suffered nervous prostration from overwork” and apparently went home. In 1916 he was at the Government Institute of Technology in Shanghai, but whether as student or teacher, we do not know.

Chang Yuing Chiu attended the University of Wisconsin for one year; after that, we have no record. He was reported to have died in 1927. Moo Ching Hou’s whereabouts after M.I.T. are also unknown. Chee Sing Hsin studied naval architecture and marine engineering at M.I.T. and was reported employed in the shipbuilding industry in Harbin in 1932, although information from M.I.T in 1936 suggests that he was associated with a middle [i.e., high] school in Zhejiang. The reports are incongruous, since the regions are some 1,500 miles apart. Furthermore, Harbin, 250 nonnavigable miles from the nearest coastal city, seems an unlikely place for shipbuilding.

Hsü Pei “Paul” Hwang became a research assistant in the Chemistry of Sanitation at M.I.T., and appears to have worked for a time as a chemist with Proctor and Gamble in Ohio, before returning to China. In 1937 he was a Commissioner of Public Utilities for the city of Shanghai, married, with 5 children. After M.I.T., Wai Gyiao Loo was affiliated in some way with the Government Institute of Technology in Shanghai, but there is no information after 1916. In 1916 another M.I.T. graduate, Yu Lin Wu, was reported to be teaching middle school in Shanghai. Tsu Mai Yu studied agriculture at Cornell, and worked in the dairy business in Shanghai. And for Chen Fu Wang, who returned to China after graduating Harvard, we have no knowledge.

Indeed, with the exception of King, we lack information on the later lives of any of Williston’s Boxer Indemnity Scholars. In a way, they disappeared into history. The period of the Chinese Republic, beginning in 1911, is not without turmoil, while the Japanese invasion of Manchuria in 1931, and the second Sino-Japanese War, 1937-1945, threw the country into chaos from which little information emerged.

After 1910

It is worth noting that while student publications from the 1870s are full of tasteless, sometimes overtly racist references to Williston’s Chinese, such obnoxiousness was not present in 1909-1910. Indeed, the senior class poll in the 1910 Log named “The Chinese young gentlemen” as having “done most for Williston.” When the Annual Catalogue was mailed in April 1910, it included a cover document from Joseph Sawyer, which stated, “Using the fund returned by our government from the Boxer indemnity, the Chinese government announces the purpose to send one hundred young men to the United States each year, for thirty years, for education, including full collegiate and professional courses. It is an epoch-making movement and forecasts a new China.” Sawyer trusted that a substantial group would attend Williston annually for the next three decades.

Alas, this was not to be. The end of the Qing Dynasty and declaration of a republic in 1911 ended the Imperial government’s tinkering with the Boxer Indeminty Scholars program. Its officials were quick to reorganize. One change was the founding of their own preparatory school in Shanghai. Henceforth no student would be sent to the U.S. until he was qualified for college entrance. Students would not come annually, but in larger groups, every few years. Ultimately five groups would come to the U.S., before the 1937 invasion and the Second World War put an end to the program.

A few Chinese would enroll independently at Williston in the next few years. Sotin Allan Chow arrived in April, 1910; he was the second family-supported Chinese scholar to whom Sawyer referred in the document reproduced above. But he took only a limited number of courses, and was gone after one term. Nine more Chinese would enter, none as seniors, from 1911 to 1916. Only one, G. Call Lieu, class of 1914, would stay more than one year. Lieu studied civil engineering at M.I.T. and ran a cement business in Guangzhou.

But the First World War effectively ended Chinese attendance until the 1920s. Yuan Chia Yung ‘25 – “Charlie” Yuan – might be considered the first in the next wave of Chinese students at Williston, even though no one from the mainland would enroll from the 1949 Revolution until 1983. For Charlie, who arrived with his two brothers in 1921, would live to see two grandsons enroll at Williston, to welcome several school tour groups to Beijing, and to return to campus for his 65th class Reunion. He is arguably the spiritual grandfather of many dozens of Chinese who have attended Williston in recent decades. But his fascinating history will need to wait for another time.

Excellent article Rick, the 1982 intersession trip to China led by your father was amazing and it was fascinating to meet Charlie at our “Peking Duck Dinner” at the end of our trip which was a truly memorable evening, inspirt the obligatory toasts with Moatai supplied by hosts.

Another terrific contribution!

All best,

Marvin