Williston Northampton’s Upper School hears an annual lecture on some aspect of school history. The event is popularly known as the “button speech,” even though most years no mention is made of Samuel and Emily Williston’s button-derived philanthropy at all. On January 30, 2013, Archivist Rick Teller ’70 spoke about diversity issues.

• • • •

Good morning. I’m here to talk about Diversity in Williston Northampton’s past. How did we get to where we are? Perhaps I should warn you: what you’re about to hear will not always be pretty. History, including our own, shouldn’t come with perfume or blinders.

It is hard to pin down when Williston first enrolled students of color. Student records simply no longer exist prior to the 1860’s. But it appears that African American students first began to attend Williston sometime in the 1870s. I can’t tell you who our earliest African American student was. The first I can name is Robert Bradford Williams, who arrived in the fall of 1877 and graduated in 1881. Williams was from Augusta, Georgia. He was a protégé of Miss Lucy Laney, who ran an Augusta school for black children, and who worked tirelessly to find places in Northern schools for students of promise. Miss Laney managed to get funding for Williams from the Reverend Joseph Twichell, a prominent Hartford clergyman and close friend of Mark Twain.

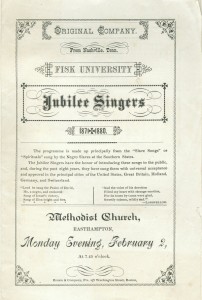

We don’t know much about Williams’ time at Williston, except that he won prizes in public speaking. But his later life is worth a brief mention: He attended Yale, class of 1885, then spent 4 years touring with the Fisk Jubilee Singers, a choral group based at Fisk University in Nashville, one of the nation’s oldest and finest historically black colleges. Williams’ first exposure to the Jubilee Singers had been right here in Easthampton, where they had performed at the Methodist Chutch in 1880. With the choir he toured Australia and Europe, and sang for Queen Victoria. In 1891 he emigrated to New Zealand, where he had a distinguished legal and political career.

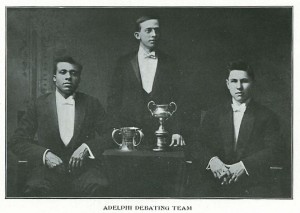

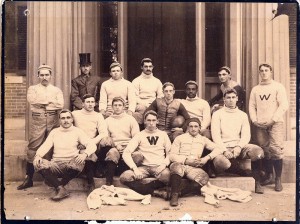

In the 1880’s we start to find photographic evidence of increasing numbers of African Americans here. When names can be connected to photographs, we can refer to the student newspaper, The Willistonian, first published in 1881, and to a variety of short-lived senior class magazines, and discover that students of color participated in such activities as debate, and on athletic teams.

We have student academic transcripts. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries some were marked “colored.” But only now and then; there was no consistency to it. Why? Does it identify a special bigotry on the part of Williston Seminary? Or did it simply reflect the times? For the situation here may have been better than at some other schools.

Take, for example, the case of Charles Fred White. White was born in 1876. When he was 15, his father forced him to leave school and find work. In 1898 he served as corporal in a black regiment during the Spanish-American War, and saw action with Teddy Roosevelt in Cuba. After the war he achieved national notoriety as an outspoken critic of the conditions under which African American soldiers served. Determined to complete his education, he enrolled at Phillips Exeter, but was expelled when Southern whites there objected to his presence.1 In 1906, at the age of 30, he enrolled in the 10th grade at Williston Seminary. Consider what it must have been like to be a 30-year-old African American combat veteran in a mostly white sophomore class.

Throughout his life Fred White had written poetry. In 1908, while still a Williston student, he published a collection of 101 poems entitled Plea of the Negro Soldier,2 the title poem of which addressed the status of black soldiers and veterans. White modeled his writing on that of the African-American poet Paul Laurence Dunbar, but I find his best work is, in many ways, superior to Dunbar’s. It is less sentimental; it does not resort to dialect; and it is angrier. Here is an example:

Shall we, who know no other home,

Who speak the native English tongue,

Submit to wrong without a groan

And leave a serf’s lot to our young?

No! We shall not. Not even beast

Will be abused without a show

Of protest. We must be released;

We must strike some decisive blow.

If we betray our fathers’ trust

Bequeathed to us upon their death

In civil war, may our base dust

Receive but curse from human breath.3

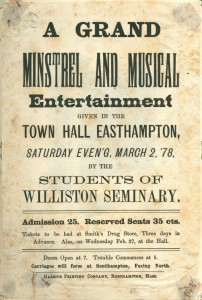

While Williston may have been generally accepting of African American students, there were frequent, even daily indignities. This was no more than a reflection of what was happening in American society beyond the campus fence, ranging from general discrimination in the Northeast to outright apartheid in the South. One can only imagine how a black student in the 1880’s or ‘90’s might have responded, for example, to the frequent student minstrel shows, in which whites darkened their faces, donned rags, and performed sketches heavy on parody dialect and ethnic jokes. These shows were a major part of middle-class white entertainment for the better part of a century.

Or consider Thomas Montgomery Gregory, class of 1906. Gregory was one of those great all-round students: academic first in his class, champion debater, athlete, editor of the newspaper, president of the senior class, and future Harvard man. Despite the universal respect he apparently commanded, his race made him ineligible for membership in any of Williston’s five fraternities. To pile insult on insult, when he and several unclubbable friends attempted to found their own frat, members of the established clubs went out of their way to block the effort.4

In 2001 I received a letter from Dave Wilder, class of 1936, accompanied by a clipping from the New York Times concerning so-called “gentlemen’s agreements,” whereby teams would leave their black athletes at home when they played all-white schools.5 The practice was common in American colleges during the first half of the 20th century. Wilder wanted to know how pervasive it had been among private schools. He recalled an incident from his senior year, in which a basketball player, George Wharton, was told not to travel to an away game because the host school would not play integrated teams. Wharton got the news from a clearly embarrassed Headmaster Archibald Galbraith just as he was boarding the bus.

With our decades of perspective, it’s easy to condemn Galbraith for going along. Perhaps he felt his hands were tied. The objecting school, which I will not name, was new to our schedule that year. But the incident, and Wilder’s letter, raised the question whether this was a common practice at Williston and other prep schools. Williston’s teams, after all, had been integrated since at least the 1880’s. So back to the Archives, where an examination of box scores for the 1936 basketball season indicates that Williston played 15 games, mostly against teams we still play. I am happy to report that George Wharton started every game except the one in question. Moreover, that school was dropped from our schedule the following year and would not appear on any Williston field or court for another 40 years, by which time they had apparently joined the 20th century. A final bit of justice: The Willistons trounced their opponents that day by 22 points, despite the absence of their starting center.

It was also in the mid-nineteenth century that Williston started to acquire an international clientele. In 1872 the government of China sent 120 carefully chosen young men to New England schools, including Williston, to be educated in the Western tradition. They were to go on to American universities to acquire skills that China’s Confucian educational system, unchanged since medieval times, was unable to provide.6

While the Chinese Educational Mission would end in 1881, thanks to internal politics back home and astoundingly paranoid anti-Chinese legislation in the U.S.,7 an international tradition had been born at Williston. Headmaster Joseph Sawyer sought to restore the Chinese presence, with such success that in 1910 there were eleven Chinese seniors at Williston, fully one quarter of the class. Meanwhile our international enrollment continued to grow. Just as an example, for the decade prior to World War I, the student population included not only many Chinese, but significant numbers from Korea, Honduras, Panama, Russia, Japan, Turkey, Mexico, and Cuba. Note the absence, except for the Russians, of Europeans on that list.

After World War Two, Mao’s revolution ended enrollment from mainland China for thirty years, but we became a popular school among well-off Thai families, some of whose descendants attend Williston today, and saw increasing numbers of students from Korea, Taiwan, and Japan. Students from African countries, especially Liberia, attended. We became involved in exchange programs with schools in Germany and England.

Sometime around 1900 we adopted a school seal which nicely symbolized not only our educational mission but our institutional world-view. It was a rather attractive disc imprinted with books, a globe and compass. There’s one on the front of the balcony, which you may examine as you leave. I want to draw your attention to the motto on the old school seal. It’s in Latin: Christo et ecclesiae. “Christ and Church.” Part of our thinking in abandoning the seal and motto in 1971 was to move away from such a strong statement of religious preference. Despite more than a century of tolerance, never in our history had we claimed to be nonsectarian. Headmaster Phillips Stevens, for whom this chapel is named, made a good case in a 1963 Williston Bulletin article that we were a nondenominational “Congregational Christian school.”8

That is consistent with Samuel Williston’s vision of 120 years earlier. Despite our “Seminary” name, we were a secular school, welcoming all, but whose teaching reflected Sam’s strongly held religious beliefs. All faculty were required to be Christian — and by implication, Protestant. The Principal had to be an ordained Protestant minister. These rules remained in effect until the middle of the 20th century. Even after they were relaxed, we had no one on the faculty who professed a religion other than Christianity until the 1970’s.

In the 19th century the Headmaster conducted daily chapel services and students were required to attend church — lengthy morning and evening services every Sunday, at the Congregational Church near the campus. By the 20th century this had devolved to a required Sunday Christian service of an hour or so in the school chapel, plus a daily 15-minute chapel service. If you were Jewish, or Buddhist, or atheist, you went anyway, and you participated. Required services ended only in the late 1960’s, in part through increased student protest but also because the chaplain, the magnificent Roger Angus Barnett, expressed growing concern that forcing the appearance of piety upon the pious and irreligious alike did little for the spiritual welfare of either. Moreover, I recall him once declaring words to the effect that sham faith was an insult not only to believers but to God Himself.

In the 1950’s and ‘60’s we had quotas for Jewish students. Let me be explicit: we do not have such quotas now. But 50 years ago, every private school did. So did most colleges. At Williston the figure was ten percent. There was an ugly code used on admission documents: “O.T.C.” — “one of the clan.”9 Jewish families knew to apply early because the quota was met quickly. There was a wonderfully twisted piece of logic to justify the practice: if there were more Jews here, then the school would become less attractive to Jewish families who wanted to send their children to Gentile schools. Richard Gregory, a former assistant director of admission, who provided me with this information, calls the logic “utterly ridiculous.”10 Quotas ended when we merged with Northampton School in 1971.

Of course, it was virtually impossible to observe Judaism in this environment. Beyond the Christian chapel services, you could forget celebrating holidays. As for attempting to keep any semblance of the dietary laws, there were no choices on the menu. Students were expected to eat what was put in front of them. I distinctly recall, ‘round about 1968, a student pointing out how inappropriate it was to serve ham on one of the major Jewish holy days. The teacher who heard the complaint stood, dumbfounded, and finally said, “You know, I don’t think anyone here ever thought of that.”

Perhaps we can understand, if not accept, institutional thoughtlessness, in an environment where all were expected to conform to a sort of prep school ideal, regardless of nationality, race, or religion. A kind of old-fashioned paternalism might have been part of it, but it is hard to stomach some of the often well-meant, but witless condescension that this entailed. Northampton School alumna Janet Wolfe recalls being told, “Now Janet, you’re our only Jewish student, so it’s up to you to represent your people.”11 That was in 1932. But I can personally attest to having heard, on multiple occasions during the supposedly more enlightened ‘sixties, a faculty member refer to a black student as “a credit to his race.”

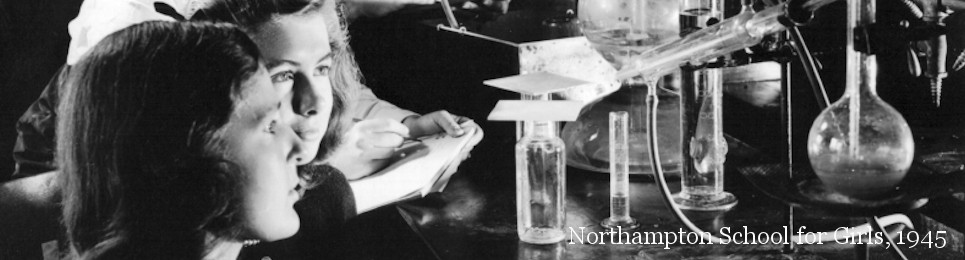

Until at least the early 1970s the majority of our black students were from Africa, rather than the United States. Similarly, we had more Asians than Asian-Americans. As for a diverse faculty — well, we had English and chemistry and history teachers . . . all of them white males. It had been that way for a century. In 1958 my mother became Williston’s first modern-era woman teacher — I’m very proud of that. I don’t think it’s unfair to state that in the 19th century our students of color came, for better or worse, with the expectation of being educated by white men in the white man’s school. That attitude may have remained a subtle undercurrent until the 1960’s, not only with nonwhite students, but with non-Christians as well. Serious efforts to diversify the faculty did not really begin until the 1980’s – initially meeting only mixed success. We’ve done a little better in the last two decades, but have a long way to go. Many factors are at work, some of which boil down to the need to identify and attract qualified minority candidates in a very competitive market. Until faculty diversity reaches that “critical mass” at which it becomes self-sustaining, it will remain a challenge not only to recruit, but to retain minority teachers. We know we have to try harder, and we do. Meanwhile, I urge some of you who have thrived in the private school environment to consider returning to it after college. It’s a stimulating life, and a great way of giving back.

In the 1970s we started to address real diversity among our student population. Our successes here have been significant. But it’s so easy to become complacent. Thirteen years ago we thought we were in a pretty good place. We seemed a happy school. A large proportion of our students self-identified as persons of color. Our senior class president was a young African American woman who had proven herself a gifted leader practically from the day she arrived in the ninth grade. Sure, there were holes in the fabric, but they mostly took the form of unfortunate events off-campus: inappropriate attention paid to students in local shops, faculty pulled over in front of their own residences for DWB . . . that’s “driving while black”. . . the kind of nonsense which, I’m happy to report, has been reduced in recent years. But on campus, all was just wonderful – until some jerk wrote a slur on the wall of our new fine arts center. “This isn’t us!,” we all declared, while many, myself included, said some fairly stupid things in aid of being helpful. But of course it’s us. Whichever “us” any of us belong to, it’s always us, and will be until the world runs out of jerks.

To this point I’ve not mentioned gay-straight issues at all. Save for a few anecdotes that do not deserve repetition, or which are terribly sad, little has been documented. Although from the mid-nineties on, we had an active Gay-Straight Alliance, I think that a majority of the school was comfortable with a kind of “don’t-ask, don’t-tell” standard. Then in 2001, our school newspaper, in a well-meant, if naive, attempt to present multiple points of view, printed an appallingly hurtful, homophobic letter. Once the dust had settled and the anger subsided, we realized that frequent, organized, intentional discussion of diversity issues of all kinds had to become a permanent feature of Williston culture, and that our evolution needed to progress beyond mere tolerance of differences. And I’m happy to note that in the past few years, as societal attitudes and laws concerning sexual orientation have matured, we have seen that evolution on campus as well.

It is a measure of our progress that on all these issues we are willing, even eager to share ideas and experiences, to be taught, to learn, to embrace, to celebrate. Another measure of progress is the quantum improvement in the civility of our discourse. While there have been and continue to be painful lessons along the way, I’m proud of my school because collectively and individually, we continue to work at this.

Have I made some of you uncomfortable? I hope so. It’s a prerequisite for progress. It is too easy to be complacent, pass judgment, congratulate ourselves on our righteousness, and go back to business as usual. That changes nothing. We may praise or condemn our predecessors, but we cannot dismiss them, for two reasons: first, that their attitudes and actions, and our response to them, shape our own thoughts and decisions; and second, that without understanding our past, it is impossible to evaluate ourselves, to measure our progress, to address our future. History is something you live; you are in our history, and you are that history. Walt Whitman wrote,

I know that the past was great and the future will be great,

And I know that both curiously conjoint in the present time . . .

And that where I am, or you are, this present day, there is the center of all days.12

Go make history yourselves. Thank you.

• • • •

1Roger J. Bresnahan, “Charles Fred White: a Forgotten Black Poet.” Negro History Bulletin 40 (1977), p. 659.

2Charles Fred. White, Plea of the Negro Soldier (Easthampton, Mass.: Enterprise Printing Co., 1908).

3White, “Meditations of a Negro’s Mind V,” Plea of the Negro Soldier, p. 135.

4Jeffrey Orson Phelps scrapbook, 1907. The Williston Northampton Archives.

5Edward Wong, “College Football: N.Y.U. Honors Protesters it Punished in ‘41,” The New York Times, May 4, 2001, sec. A, p. 1; and David Wilder to Rick Teller, May 4, 2001. The Williston Northampton Archives.

6Thomas E. LaFargue, China’s First Hundred: Educational Mission Students in the United States, 1872-1881 (Pullman, WA: Washington State University Press, 1987).

7Ibid, p. 41-58.

8Phillips Stevens, “Credo of the Headmaster,” The Williston Bulletin 50:1 (Autumn 1963), p. 5.

9Assistant Dean and history teacher Dave Koritkoski told me he had come across the initials elswhere, and had understood them to mean “other than Christian.” That may have been the official, as opposed to colloquial, interpretation, but I don’t believe it fundamentally changes anything. [Au.]

10Interview with Richard Gregory, June 26, 2002, Easthampton, Mass.

11Conversation with Janet Wolfe, June 8, 2002, Easthampton, Mass.

12Walt Whitman, Leaves of Grass, Book XVII, “Birds of Passage,” “With Antecedents.” In Whitman, Collected Poetry and Complete Prose (New York: Library of America, 1982), p. 383.

© Richard Teller, 2002, rev. 2007, 2008, 2013.

Your comments and questions are encouraged! Please use the form at the end of the article.

Rick, I just recently found you “blog” and am so very pleased that you have taken on this huge project! Learnng of the past is so important to the future. I am just starting to read them all.

Thank you. Your Mom would be so very proud! I loved her.

Marilyn Francis

lovely to come across this webpage when searching about my great grandfather Robert Bradford Williams –

Thanks for referring me to your article! I find Williston’s history quite interesting. As you know, I am looking forward to finding out more about African-American students there during the 1880s.

“Whichever “us” any of us belong to, it’s always us, and will be until the world runs out of jerks.”

We can only hope.