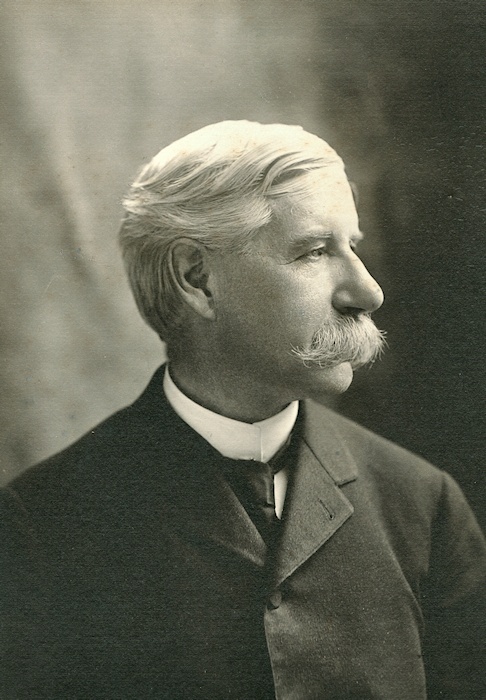

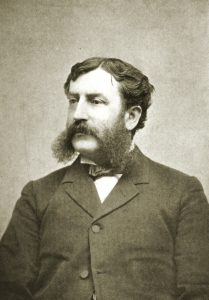

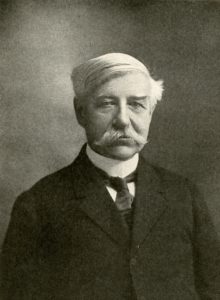

“A tall spare man slightly stooped with untrimmed gray moustache and formal tail coat was for long years a familiar figure to both campus and town. He was one of those persons who was always going somewhere, always on duty, and not given to casual conversation. ‘See me in my office’ was his characteristic invitation . . . ‘Old Joe’ was a host in himself. And what a complex of competing interests: schoolmaster who wanted to be a preacher, strict disciplinarian whose heart was always giving way before a youngster’s tearful plea, living laboriously in the present and yet clinging wistfully to a past long since gone by, most serious of countenances lightened at times with the pleasantest of smiles.” (Howe, 1)

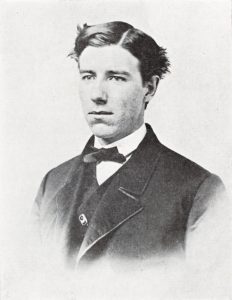

Joseph Henry Sawyer. Williston’s longest-serving faculty member was here for 53 years, a record that no one else has even approached. That could simply be another piece of Williston lore, like the numbers on the fence or the cow in the tower, were it not that Sawyer took himself seriously as an historian and wrote a useful history of the school. He counted Samuel and Emily Williston among his friends. He knew all six of his predecessors as Principal or Headmaster, as well as his successor, Archibald Galbraith. There are hundreds of living alumni, this writer included, who knew Galbraith. His life is a kind of time travel, a bridge between centuries. So Sawyer’s longevity is enough to warrant our interest, but there is much more.

He had really hoped for something other than teaching. Though conservative by instinct and by preference, he became our most innovative Headmaster, although he had never sought the job.

Background

In advance of the Williston centennial in 1941, Herbert B. Howe, class of 1901, attempted a Joseph Sawyer biography. Howe was a competent historian and indefatigable researcher. Yet he found Sawyer to have been so self-effacing that his life away from Williston was nearly undiscoverable. The son of farmers, Sawyer was born May 29, 1842, and raised in Davenport, Delaware County, New York, some 70 rural miles southwest of Albany. Young Joe did well enough at school for his parents to agree to send him for one year to the nearby Fergusonville Boarding Academy. There, Sawyer discovered the joys of the laboratory and the library. Against his nonetheless proud parents’ expectations, Sawyer won a scholarship to Amherst College. Arriving there in 1862, he found that he was sufficiently advanced to be granted sophomore status.

He graduated in 1865, a member of Phi Beta Kappa and in a three-way tie for Valedictorian. Along the way he had decided to become a clergyman. However, this would require graduate study which, at the time, Sawyer could not afford. Having excelled in mathematics, he took a teaching position at Monson Academy, now Wilbraham and Monson.

A year later, Principal Marshall Henshaw, himself an 1845 Amherst graduate, hired him to teach at Williston Seminary. The road between Amherst and Easthampton was well-traveled in both directions. Many Williston graduates went on to Amherst – 14 of Sawyer’s 57 classmates had prepped there. Many returned to Easthampton to teach. Samuel Williston was an Amherst trustee. It is not impossible that Henshaw and Sawyer knew one another; at the very least, Henshaw was likely to have known that Sawyer was among the elite scholars in his class. So when teacher Judson Smith (Amherst ‘59) decided to move on, Amherst Mathematics Professor Ebenezer Snell recommended Sawyer to replace him.

Sawyer was hired as a teacher of pure and applied mathematics and something called “mental philosophy” — we now call it psychology, plus economics and history. Later in his career he would teach surveying and English. Teachers had to be multi-talented in those days. They had to be tireless, as well; the typical course load was six one-hour classes, every day.

Sawyer was 23 years old. One never knows how long young faculty will stay. Then, as now, many would teach for a couple of years and go on to grad school, or decide that teaching wasn’t for them, or find a school with greener grass. His initial plan appears to have been to recover his finances and then resume his education, but for whatever reason – and Sawyer is characteristically silent on his motives – he stayed.

Certainly he found academic life congenial; he always had. And under Henshaw, who was uniquely talented in getting Samuel Williston to fund new endeavors, Williston Seminary was undergoing exciting changes, with a new gymnasium just completed, a residence hall under construction, and state-of-the-art science facilities that rivaled Amherst’s and Harvard’s. The faculty included several Amherst men under the age of 30. Joe Sawyer must have felt right at home.

Somehow, despite his demanding schedule, Sawyer had pursued graduate study. He was awarded a Master of Arts degree at Amherst in 1868. Dr. Henshaw immediately named him Assistant Treasurer. Truly, Sawyer seemed a glutton for work.

Meanwhile, his life was about to change. Sawyer, along with a couple of other bachelor faculty, stayed at a Main Street boarding house maintained by a Mrs. Henry Beekman. (Running boarding establishments was often the province of widows without other income.) Mrs. Beekman had three daughters. The middle daughter, Sarah, had graduated Williston in 1861 and Mount Holyoke in 1866, where her closest friend had been Sabra Snell, daughter of Ebenezer Snell, Sawyer’s mathematics mentor at Amherst. So it is conceivable that Sarah and Joe had known one another since his college days. In any event, something clicked. They were married on June 29, 1870. Sawyer was putting down roots.

The Alumni Records

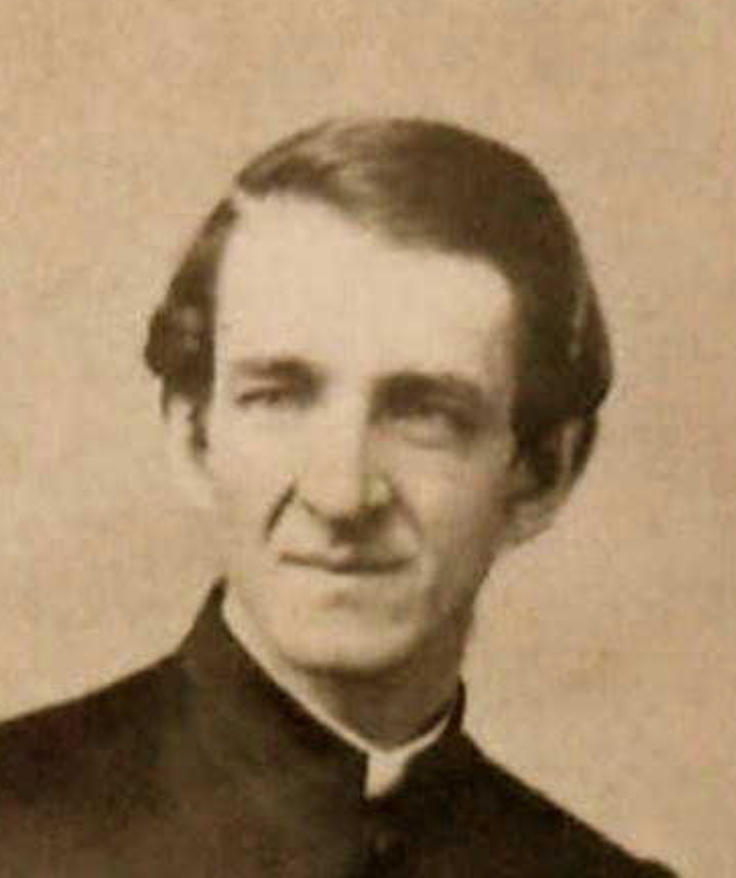

It is fascinating how events fall into place. The day before his wedding, June 28, 1870, Sawyer heard Henry Clay Trumbull address the Williston Alumni Association. (At the school’s 25th Anniversary in 1866, Principal Henshaw had advanced the creation of an Alumni Association, which met annually in conjunction with Commencement exercises.) Trumbull, Williston ‘44, had distinguished himself as a Civil War chaplain, and was the leading advocate for the growing Congregational Sunday-School movement. He was, by all accounts, a stirring speaker. In his remarks on “The Worth of a Historic Consciousness,” Trumbull made the case that a school was less bricks and mortar, less curriculum, than the sum of the experiences of the people who had gone before. He particularly cited the great English public schools that had served as the Founder’s models three decades earlier. Trumbull concluded with a challenge to the Williston Trustees and Faculty to create, publish, and maintain a comprehensive alumni record that would “stimulate a historic-consciousness in the minds of all who are students here.” “You will honor, not the alumni, but yourselves.” (Trumbull, 45)

Sawyer was hooked. But he had a honeymoon, a home to set up, and increased school responsibilities to attend to. Meanwhile, the alumni record project had been offered to a recently retired faculty member living nearby. Very early in the school’s history an attempt to track alumni through a “Memorandum Association” had been initiated, but the project was abandoned in 1848 (see “A Perfect Paradise on Earth“). After more than a year the former teacher charged with picking up the pieces, but frustrated by the school’s failure to have maintained addresses for a majority of its alumni, reported little progress.

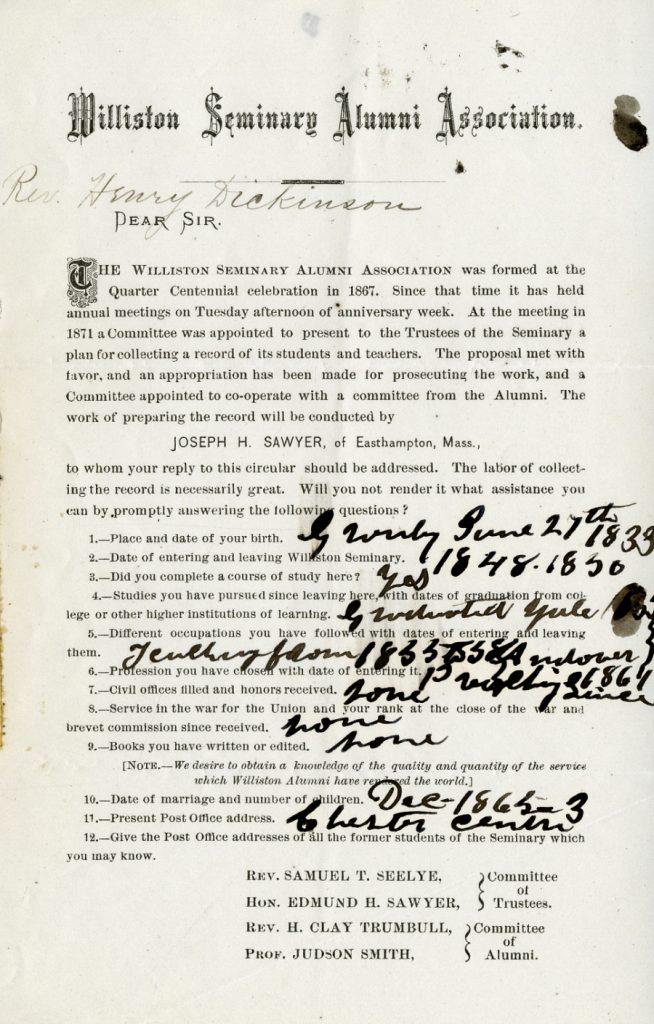

So Sawyer, newlywed, already doing two jobs, volunteered. This meant shoehorning the work into weekends, vacations, and late evenings. It was a massive undertaking. Hundreds of former students needed to be tracked down. Sawyer organized a group of class agents who might know the whereabouts of school friends, wrote to home town parish ministers, and generally cast his net wide. Once a former student had been found, he received a survey form. From this, a biographical record of alumni, 1842-1874, gradually grew. The work entailed hundreds of hours, and hundreds of pieces of mail.

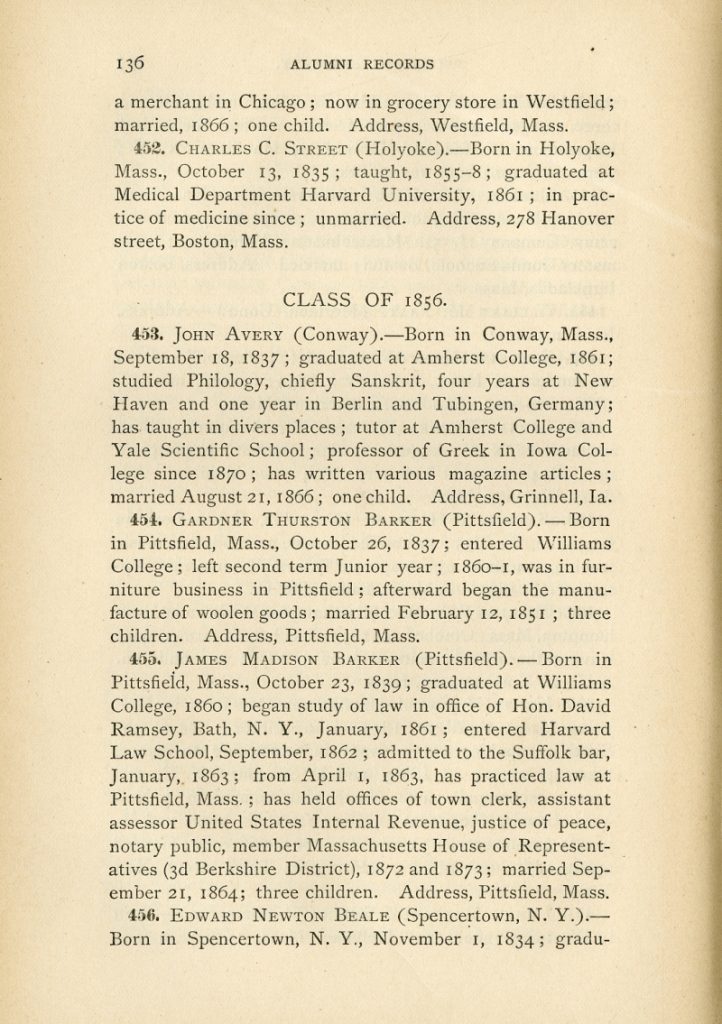

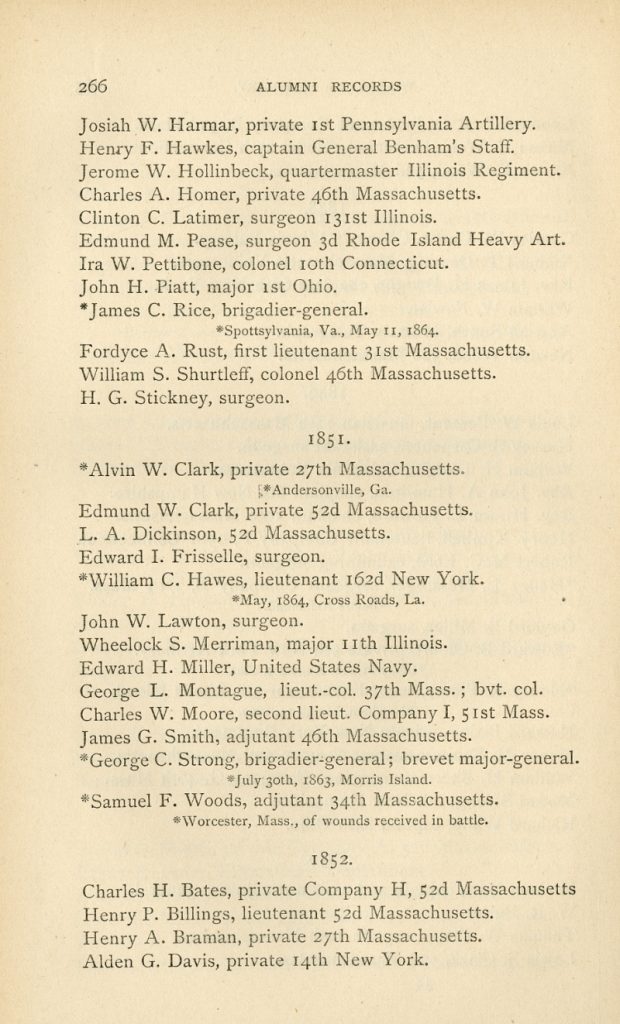

The Williston Seminary Alumni Records were published in 1875. They contained not only a roster of each of the 4,966 male students who had enrolled through 1874, but biographical information, sometimes in considerable detail, for nearly one-third of them. Sawyer identified the 1,077 women who had attended through 1864 and, in most cases, their married names and residences. This appears to have been the first effort since the demise of the Memorandum Association to acknowledge female alumnae at all. Sawyer had also tracked down every former teacher and trustee and was able to provide biography for most of them. The volume also included a census of alumni in various professions and colleges attended, and a “Role of Honor,” listing the class, regiment, and rank of alumni and teachers who had participated in the Civil War, including the date and place of death for those who had fallen. This section was compiled by Sawyer’s faculty colleague Henry H. Goodell, class of 1858.

The Alumni Records remain among the most useful primary sources for the history of Williston’s 19th century. Their compilation created a model for future alumni record-keeping – the more so since Sawyer included an appeal for former students to keep writing in. This they did, and Sawyer, until he was able to hand the job off to someone else years later, became Williston’s de facto Alumni Secretary.

Service and More Service

Sawyer had not forgotten his early ambition to be a minister. During this extraordinarily busy period, he also found the time to prepare for his eventual ordination. In June, 1872, the Hampshire Association of Congregational Ministers granted him a license to preach. Full ordination would not come until 1888, but from this point forward Sawyer was a regular guest minister in Easthampton and in churches up and down the Valley.

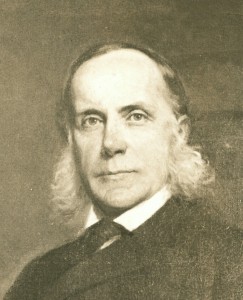

In July, 1874 Samuel Williston, aged 79, died. He and Principal Marshall Henshaw had enjoyed an especially close relationship, possibly because Henshaw had been the first of Williston’s CEOs to stand up to him, something that Sam respected. As noted above, the Seminary had thrived, illuminated by Henshaw’s vision and Williston’s purse. But while Williston had provided for an endowment, much of it was in securities not yet matured. The reality was that he had suffered serious financial losses in the postwar industrial recession. Henshaw could no longer rely on the Founder to meet expenses, and Emily’s charitable interests – sometimes rather pointedly – lay elsewhere. Deficits began to mount. Meanwhile, factions developed on the faculty, some of whom wanted more autonomy, and the Board of Trustees, which wanted to reassert itself as the source of both funds and policy.

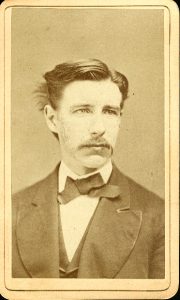

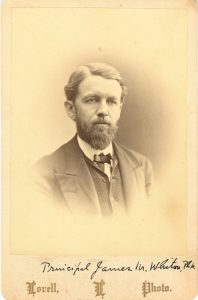

In part through the machinations of a couple of faculty members, Henshaw resigned in 1876 and joined the faculty at Amherst College. His replacement, James Morris Whiton, a megalomaniac lacking any skills in student or community relations whatsoever, was so spectacularly unsuccessful that he lasted less than two years. (For a little more concerning this chaotic time, see “Sawyer the Historian,” below.) Sawyer, meanwhile, continued to meet his classes and pursue his administrative work. He seemed to have a talent for remaining uncontroversial.

In 1878 Joseph Whitcomb Fairbanks, Williston ‘62, Amherst ‘66, was appointed Principal. Notwithstanding his spectacular set of side-whiskers, Fairbanks turned out to be one of the invisible men in our history. There was no question that the Board was in charge of all major decisions. But Fairbanks seemed to have little interest in day-to-day administration, either, and was happy to leave most of it in Joseph Sawyer’s capable hands. A cynic might observe that this also provided Fairbanks with a scapegoat, should circumstances demand.

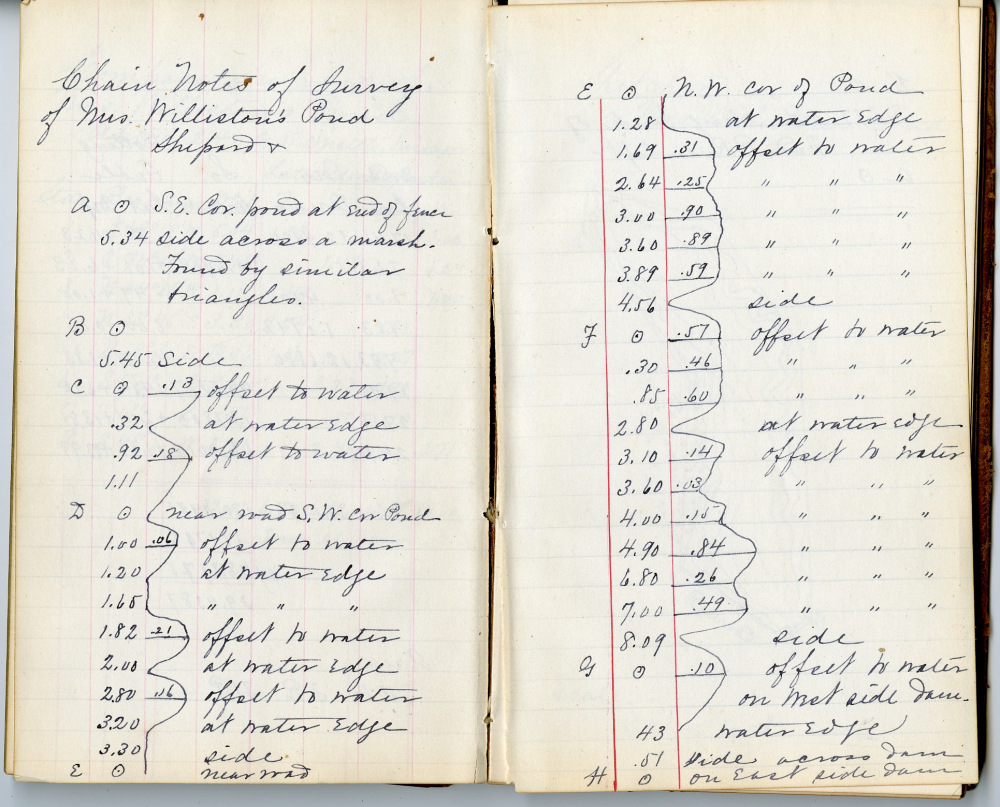

Furthermore, the citizens of Easthampton had discovered that Sawyer, instinctively committed to service, more than competent at anything he set his hand to, was indispensable to them, as well. In 1878 he was elected to the School Board, which he would eventually chair. He joined the Water Board and chaired the Sewer Commission for a decade. On several occasions he moderated the Town Meeting, New England’s traditional all-in contribution to participatory democracy. He was considered fair and committed to ensuring that every voice was heard. He volunteered the services of his surveying classes to lay out plans for a new waterworks and to survey a great many Easthampton properties. He became a Deacon in the Congregational Church and – Trumbull’s influence, no doubt – Superintendent of the Sunday School. One wonders if he ever slept.

Acting Principal

In the spring of 1884 Sawyer, citing 18 years uninterrupted service, petitioned for and was granted a leave of absence. He and Mrs. Sawyer anticipated a long, restful European sojourn. It was not to be. Tensions between the increasingly assertive Board of Trustees and Principal Fairbanks had not remained dormant for long, and were complicated by strong feelings on the faculty, who, not unreasonably, felt that they deserved a role in making policy, and by a student body whose interests, when not distracted by trigonometry and irregular verbs, ran more and more to riotous behavior. That same spring, Fairbanks suddenly resigned.

The Trustees were unable to agree on a successor. They suggested that the faculty run the school, electing one of their own to serve as Acting Principal. Sawyer’s colleagues selected him. He was the only logical choice; he got along with everyone, knew the operations of the school inside and out, and had been doing most of the work anyway. It was supposed to be an easy job, in which the Board would make all the tough decisions, and was expected to last a few months at best. So the Sawyers’ sabbatical was postponed.

No one anticipated that two years would pass before the Trustees got around to selecting a head. Status quo seemed fine, although 30 years later, in his history of the school, Sawyer would comment on how damaging it had been. The Reverend William Gallagher was eventually appointed in 1886. With Fairbanks, he shared magnificent sideburns and a talent for laissez-faire disengagement. His travel plans on indefinite hold, Joe Sawyer went back to being administrator-of-all-things. It was not until 1896 that he and Sarah were finally granted the leave they had sought twelve years earlier.

We have noted that Joe Sawyer appeared to be universally respected. Certainly he was a consensus-builder, with a talent for finding areas in which opposing factions could seek compromise — although close examination of his writings suggests that he sometimes managed to be on both sides of some issues.

Headmaster

But being all things to all people isn’t a bad talent for a leader to have. In June of 1896, the invisible Gallagher, having served 10 years, suddenly resigned. The Trustees were faced with finding a Principal on very short notice. Remembering Sawyer’s ability to build consensus, noting that he’d been doing most of the work anyway, and probably counting on his tendency to be uncontroversial, they selected him. Sawyer, who had neither applied for nor expected the job, was enjoying his long-delayed European tour at the time. His return to Easthampton brought, to say the least, a surprise.

Sawyer protested that his health was shaky, that he was, at 54, older at the start of his service than any other heads had been when they left — even that his long association with the school, which the Board considered such an advantage, might actually be a drawback. He noted that no member of the faculty had ever been elevated to Principal, and that there were obvious reasons why it didn’t seem a good idea. He had, after all, vivid memories of the factionalism that had brought down Marshall Henshaw twenty years earlier. The faculty responded with a unanimous pledge to stand by him. It is very possible that the Board was counting on Sawyer’s age, health, and uncontroversial nature to result in a short, uneventful term of service followed by his gracious retirement. They could not have been more wrong.

Only with the pledge of faculty support did Sawyer reluctantly hang his coat in the front office and get to work. His first task must have been to convince the Trustees to let him work. To its credit, the Board, many of whose more assertively conservative members from the post-Samuel years had died or stepped down, was willing to listen. If nothing else, their commitment to Samuel Williston’s vision of half a century earlier was clearly no longer practical. It became apparent almost immediately that Sawyer had what no Williston leader had shown since Henshaw: a vision of his own.

A New Williston

The school had undergone little curricular or social evolution in 20 years, the finances were a mess, and enrollment was unstable at best.

In the half-century since Williston was founded, the educational demands of universities and the workplace had changed. The classical-religious curriculum and Samuel Williston’s science academy were becoming less and less relevant. Under Sawyer’s leadership, a comprehensive curriculum would evolve, resembling something we would recognize today — although it would be left to his successor, Galbraith, to abolish the classical-vs.-scientific divisions. Headmaster — he was the first to adopt the title — Sawyer’s vision of Williston was of an institution which involved its students around the clock. It was thus under his leadership that school-sponsored athletics came into their own, and that the faculty took on substantial social and advisory roles in their students’ lives. Sawyer also began a program of long-range planning, to address the development of the Homestead property – the present campus – that would include a new residence hall and modern outdoor athletic facilities.

Money was the real problem. When Emily Williston died in 1885, she left the school the Homestead land, with the proviso that the Principal live in the mansion and that the school erect at least one new building. Twenty-five years would pass before construction could begin. The fact was, Samuel’s endowment was tied up in securities that had not yet matured or factories that were no longer productive. Williston had suffered some serious business losses toward the end of his life, having failed to understand that in the post-Civil War economy, it no longer made sense to ship cotton north for milling when there was cheap blue-collar labor in the South. The reality was that the school was entirely dependent on tuition income to meet expenses.

Meanwhile, the physical plant was aging, and the school was paying for the upkeep of the Homestead property without using it. The school’s debt exceeded $50,000 — a vast sum for the time. Sawyer imposed rigid economies and, after many years, retired the deficit. But to bring about his envisioned physical and social changes, Sawyer had a truly controversial idea. We take it for granted now: asking the alumni for support.

Fundraiser

“It won’t work,” he was told. “People think the school is rich and won’t believe it when you ask for contributions.” That turned out to be true. And, because it had never been done before, there was something uncomfortable about asking — Sawyer himself, in a rare moment of self-disclosure, writes of his “distaste for the part of beggar.” (History, 328) In 1899 he tried to raise $25,000. He failed, in part through his own inexperience. Undeterred, he tried again. His goal was $100,000. He raised only $6,500. A third attempt was no more successful. A less stubborn man would have thrown in the towel. But by the time Sawyer began his fourth campaign, people were starting to believe him. Major gifts, from alumni Cleveland Dodge (for whom the Dodge Room is named) and John Howard Ford inspired other donors, and the Annual Fund was born. In 1901 the pasture opposite Emily Williston’s pond was developed as a modern outdoor athletic field, complete with grandstand and dressing rooms. The Trustees insisted it be named Sawyer Field. Through the generosity of John Howard Ford, construction of Ford Hall in 1915-16 opened the present campus to student use, and provided more flexibility in the use of the original school buildings downtown. (See “Ford Hall Turns 100” for a sense of the rough-and-ready approach to fundraising in those days.)

In 1915, the Williston Bulletin first appeared. In it the school could not only communicate its successes, but its short- and long-range aspirations and needs. It was, moreover, a vehicle for alumni news. So it remains. In addition, Sawyer had elevated the annual commemoration of Founder’s Day to a major Commencement Week event. While it is arguable that his reverence for Samuel and Emily helped to perpetrate some of the hoarier legends, the celebration was meant to inspire students, just at the time many of them were about to go out into the world. In 1911 Sawyer published and distributed to the alumni four of his more eloquent Founder’s Day addresses. They were a reminder of the importance of loyalty, perseverance, and the responsibility to pay forward. (See “Founder’s Day” for the full text of one of those speeches.) Founder’s Day, now a February observance, remains a key element in Williston’s Advancement calendar. It will next be celebrated on February 17, 2021.

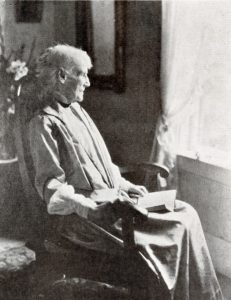

Valedictory

The school grew, had a direction, all was going well — and then World War One began. As young men enlisted, enrollment melted away. In 1919 there were only 13 seniors at graduation. Without tuition income, deficits mounted quickly. A popular French teacher, Robert Pellissier, had left to join the Canadian infantry, and was killed in action. Other alumni and students followed. Sawyer must have seen all he had worked for his entire life crumbling away. His last known, grainy photograph is almost heartbreaking. He has turned to pose for an impromptu snapshot. The rakish mustache is there, and his morning cigar, but he cannot manage a smile, and everything droops, as if responsibility was quite literally pressing him down. Pleading exhaustion, ill health, and advanced age — he was 77 — Sawyer tendered his resignation, pending the appointment of a replacement. Archibald Galbraith was selected. Sawyer never actually had a chance to move out of the Homestead. In November, just a few months after his last Commencement, he was dead.

Sawyer would never know that the foundation he had built was solid. With the end of the war, enrollment recovered, his legacy of good management soon had the ledgers in the black, and his school evolved rapidly and positively. Would that he could have seen it.

Sawyer the Historian

Diplomat that he was, Sawyer must have known that attempting a comprehensive history of the school was like walking into a minefield. His acquaintance, often friendship, with all of his predecessor Principals, with so many former faculty, lent him credibility. As a young teacher, he had cultivated a friendship with the aging Samuel and Emily Williston, who had told him stories of their aspirations and adventures in the early days of Easthampton industrialization and the beginnings of the school. Emily had actually confided to him what may be the most credible version of the button legend. One has a sense that from early in his career, Sawyer had been compiling information for the book it would take him half a century to write.

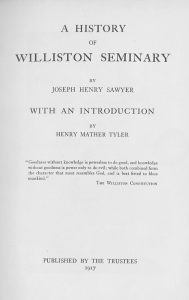

On the other hand, many of Sawyer’s subjects were still living, still serving on the faculty or Board of Trustees – or descended from them. The book’s anticipated audience largely comprised alumni, whose memories and loyalties were quite naturally focused upon the events and people of their times. Exacerbating the dangers was the plan to publish at a time when the school was trying to create a culture of giving dependent upon alumni goodwill. Indeed 1917’s A History of Williston Seminary was part of that effort.

The volume remains useful to this day, but to this writer’s sensibilities, suffers from the author’s innate modesty, and even more from being an “official” publication. Frequently Sawyer refuses to give himself credit. He does not even name himself as the principal editor of his first triumph, the 1875 Alumni Records (even though his name appears on the title page), nor the culture of alumni engagement that the project engendered. And as a history, the book isn’t critical enough. Too often, Sawyer goes out of his way to be kind.

And sometimes it’s worse than that. Earlier, as well as in our last article, we touched briefly upon the short, unhappy reign of Principal James M. Whiton, whose inability to manage students, local relations, or the press cost him his job after less than two years at the helm. That Whiton had attempted to reign over chaos is well-documented, in student publications (which may be approached with a certain skepticism), the local and national press (somewhat more objective in the aggregate), and the completely dispassionate records of the Board of Trustees. Yet Sawyer, after a wordy preamble, dismisses the anarchy of 1878 with “A few, beginning with boyish mischief, went on to things worse, and enlisting the aid of newspaper reporters, they began manufacturing sensations.” Sawyer then baldly states that at the close of Whiton’s second year, “the report from the treasury showed a deficit reduced by one-half, but still too large to be permitted to continue. After the close of the school year in 1878 Dr. Whiton resigned.” (Sawyer, 220)

This, alas, is utter fiction, borne out not only in the Board records but in Whiton’s own journals. But over the ensuing decades Sawyer made things worse by attempting to rehabilitate Whiton’s record, commissioning his portrait for the Chapel and even, on one occasion, inviting him back to preach. A century later, it only calls Sawyer’s credibility on other issues into question.

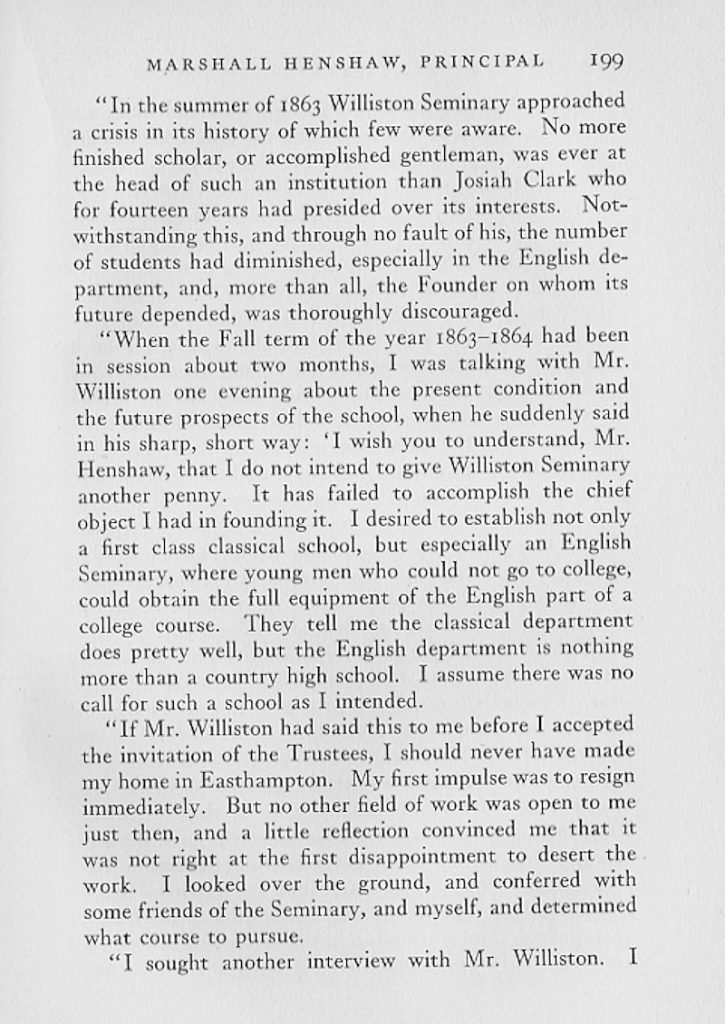

Sawyer comes off a little better in the matter of Principal Marshall Henshaw, who had convinced Samuel Williston to expand the Seminary’s endowment. In telling that story, Sawyer writes, “Near the close of his life [thus, ca. 1900] Dr. Henshaw committed to the keeping of the writing of these pages a paper, with the request that it be held in confidence until such time as should be fitting or permissible for its publication. If no opportune time came, the paper was to be destroyed, or buried within the archives of the school. (Sawyer, 198; italics mine.) Sawyer then reproduces the entire document, “without comment.” (Sawyer, 199-204) A portion is below:

Well, not quite entire. Sawyer added nothing, but he edited with a heavy hand, and excised potentially controversial text. For example, following the phrase “I do not intend to give Williston Seminary another penny,” Sawyer cut Williston’s next sentence, “I have often wished the whole thing at the bottom of the sea.” Innocuous enough, perhaps. But Sawyer deleted Henshaw’s final paragraph in its entirety:

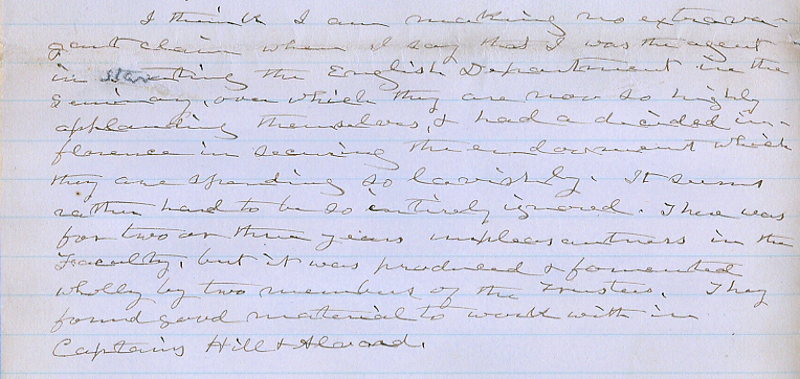

“I think I am making no extravagant claim when I say that I was the agent in starting the English [i.e., Scientific] Department in the Seminary, over which they are now so highly applauding themselves, & had a decided influence in securing the endowment which they are spending so lavishly. It seems rather hard to be so entirely ignored. There was for two or three years unpleasantness in the Faculty, but it was produced and fomented wholly by two members of the Trustees. They found good material to work with in Captains [David] Hill and [Henry] Alvord.” (We have met Captains Hill and Alvord elsewhere. Everything indicates that they were master, if unsubtle, manipulators.)

There are all kinds of good and bad reasons for Sawyer to have cut this paragraph. But to his credit, he was too committed an historian to destroy the manuscript. Instead, he followed Henshaw’s suggestion that it be “buried within the archives of the school” to the letter, inserting it in a large, dull file of Samuel Williston’s business records, whence it emerged almost a full century later, in 1997. It is almost as if he had planned for this writer to find it.

Sources Cited

Herbert Barber Howe. Joseph Henry Sawyer, 1842-1919: a Brief Sketch of the Life of the Seventh Headmaster of Williston Academy. Easthampton, Mass.: Williston Academy, 1941.

Joseph Henry Sawyer. A History of Williston Seminary. Easthampton, Mass.: The Trustees, 1917.

Henry Clay Trumbull. The Worth of a Historic Consciousness: an Address to the Alumni Association of Williston Seminary . . . June 28, 1870. Hartford, Conn.: Case, Lockwood, & Brainard, 1870.