One of the highlights of May 2020 was to have been the Williston Theater’s much-anticipated presentation of Les Misérables. The COVID-19 crisis having closed the campus, it was not to be. It would have been an opportunity to publicly celebrate the centennial of The Williston Theater, which made its debut (as the Dramatic Club) in 1919-1920.

Prehistory

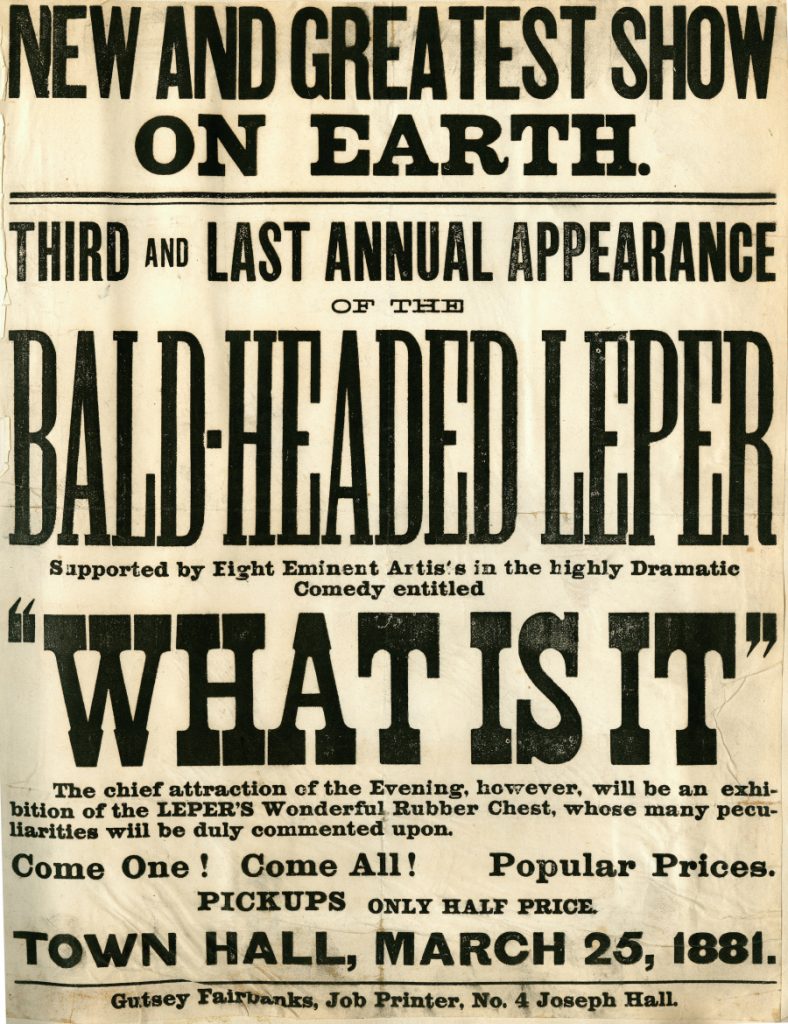

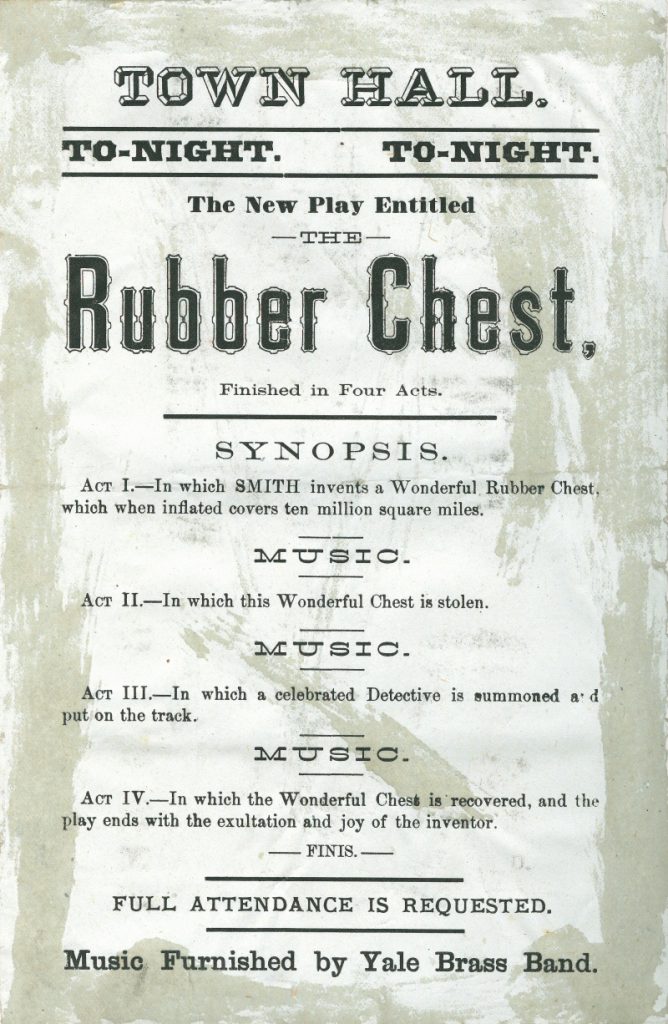

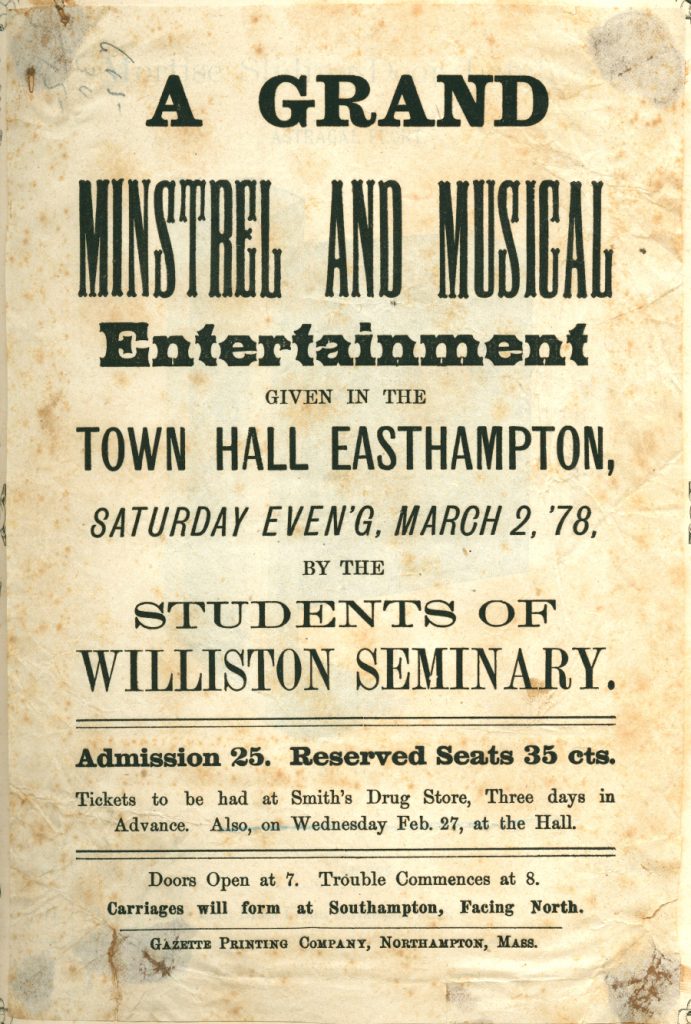

To be clear, student theatricals were regular occurrences at Williston Seminary (as it was then called) prior to 1919. Teenagers have always been dramatic, and the “hey kids, let’s put on a show” instinct, often coupled with an urge to clown, is rarely far from the surface. Most of the student-produced shows of the time took on a rough-and-ready quality. Today we might call it skit comedy, and would probably be baffled by inside jokes and perhaps disappointed by the overall taste.

For a nominal fee, Williston students had the use of the auditorium and stage in the Town Hall, directly across Main Street from the campus. Although the building belonged to the town, it had been donated by Samuel Williston, and students made certain assumptions.

In some instances, we might be more than disappointed at the tone of some of these efforts. “Appalling” is perhaps not too strong a word to describe student minstrel shows that featuring stereotypical characters and ethnic humor. Reflecting the times, the targets were most frequently African Americans and the Irish. Ironically, Williston was an integrated school by the 1870s. One can only speculate on how students of color might have responded.

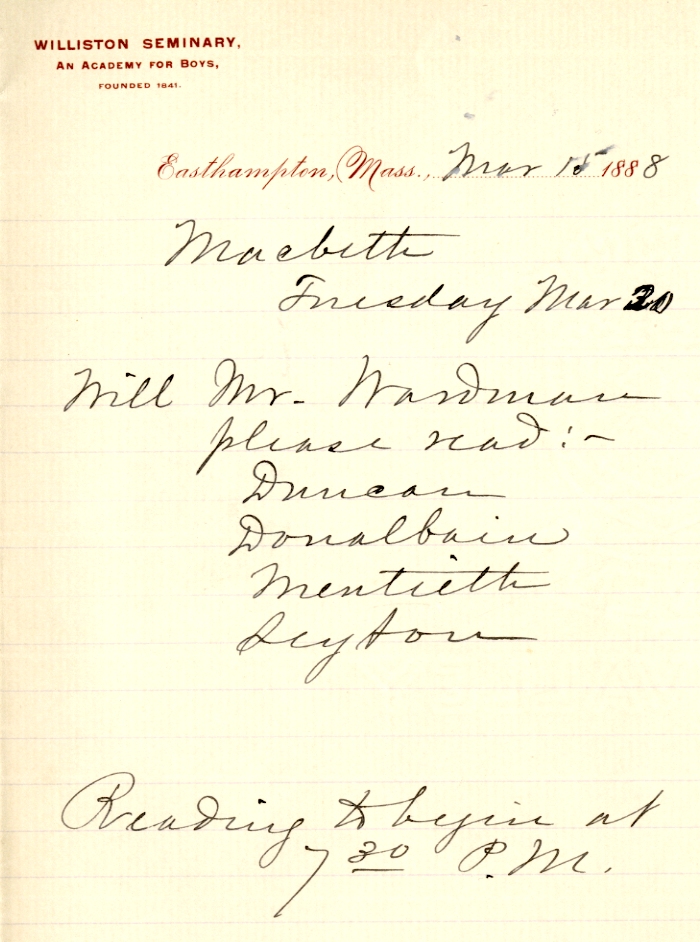

Happily, some aspired to loftier dramatic pursuits. George Wardman, class of 1889, was one of a cadre of theater-mad students invited to participate in a faculty reading of Shakespeare’s Macbeth in 1888. Participants read multiple roles, and the female parts were undertaken by faculty spouses — Lady Macbeth by the Headmaster’s wife. The organizers were sufficiently pleased with themselves to attempt Hamlet a few weeks later. (Wardman preserved his invitation and cast list in a scrapbook full of other theatrical memorabilia; see An 1880s Williston Scrapbook.)

The Birth of the Drama Club

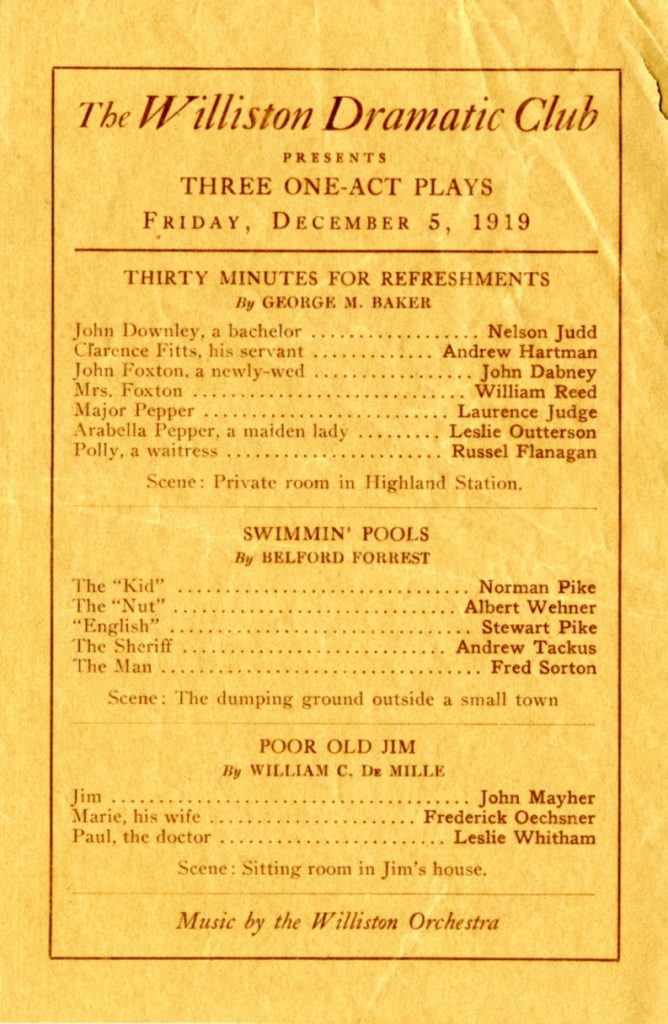

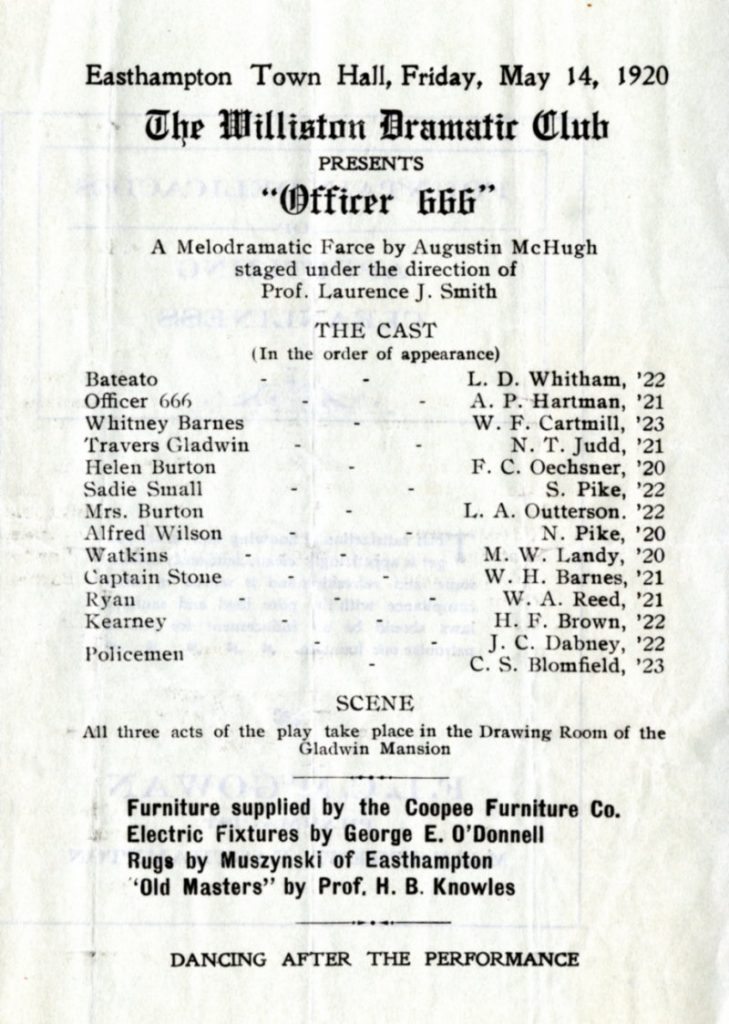

Student productions up prior to 1919 had enjoyed neither school sponsorship nor faculty supervision. All that changed with the 1917 arrival of Professor Laurence J. Smith, an English teacher and graduate of what was then known as Emerson College of Oratory. Smith set about convincing colleagues and students of the importance of “the promotion of the art of the theatre and the development of self-confidence and imagination through dramatic expression.” In October 1919, under Smith’s direction, a student cast took to the Town Hall stage with an evening of one-act plays. (The program is at the very top of this article.)

Why the sudden change in direction? As any actor will tell you, timing is everything, and Smith’s timing was perfect. Smith had been able to prepare the ground with Headmaster Joseph Sawyer who, in 1918-19, was in his final year at the helm. For several years Sawyer had been advocating his vision of “the new Williston,” in which faculty would take on ever-increasing roles in students’ lives outside of the classroom. This was something in which Sawyer’s successor, Archibald Victor Galbraith, passionately believed. Here was an opportunity to put theory into practice. Senior faculty were cautious, but Smith was exactly the sort of energetic young teacher whom Galbraith was happy to encourage.

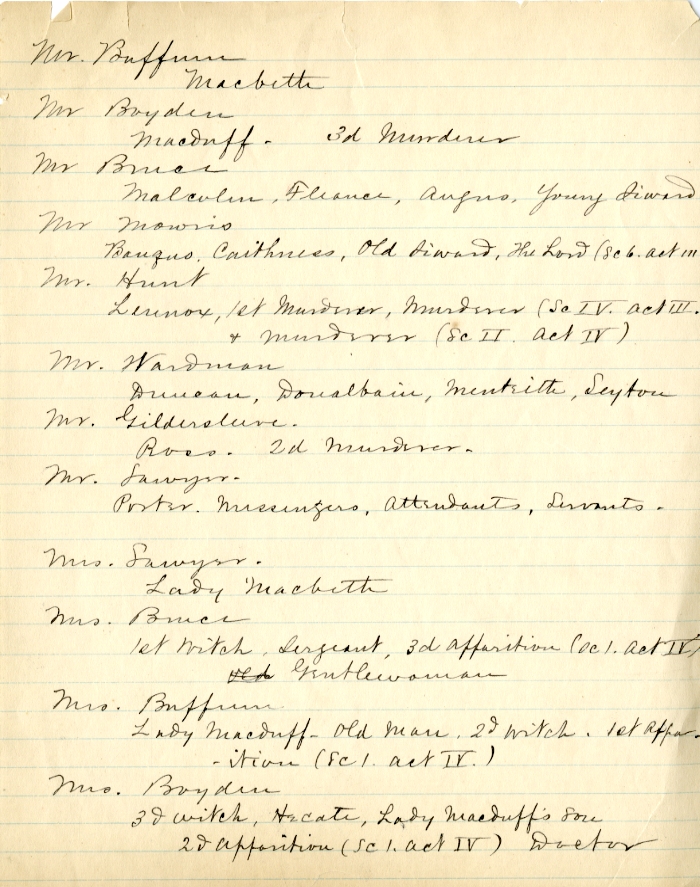

In addition, in the spring of 1919 the Glee Club, at the suggestion of Sgt. Lincoln Graham, an invalided World War I veteran who supervised student military drill, departed from their usual formal spring concert and presented a staged recreation of an army camp entertainment. Graham and another young faculty member, Earl Johnston, also appeared in the show. By all accounts it was a rousing success. With signing of the Armistice the following November, Graham departed and the student militia was disbanded, but the precedent for school-sponsored public theatrical entertainment had been set.

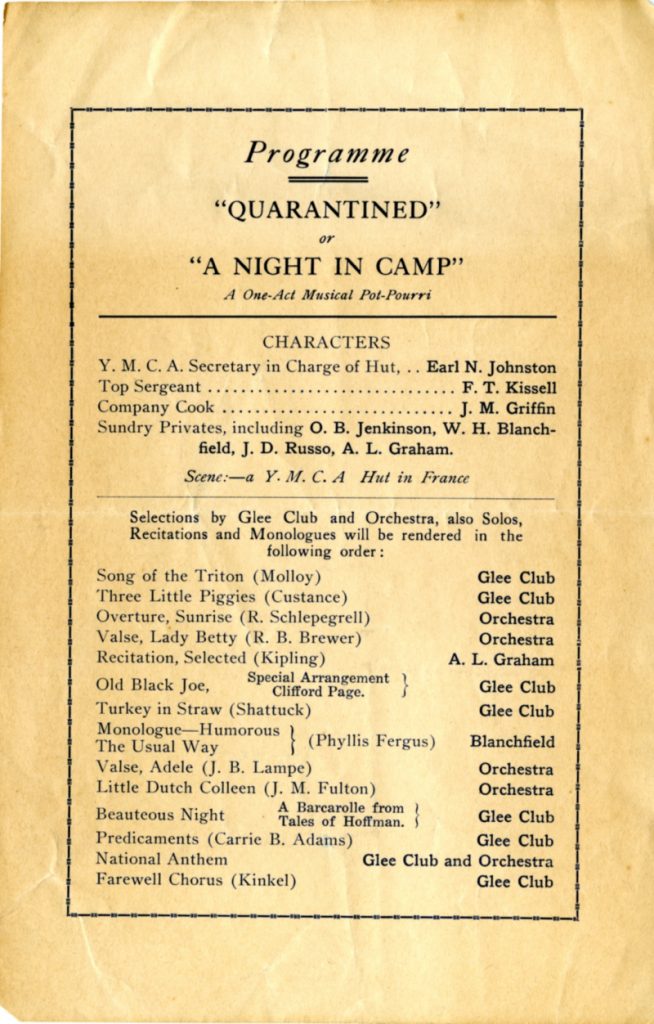

Having begun with three short plays, Laurence Smith was ambitious. Williston had never put on a “real” full-evening play. Despite lukewarm encouragement from the faculty (see Faculty Meetings a Century Ago, the entry for April 30, 1920), Smith selected a popular contemporary play: the “melodramatic farce” Officer 666.

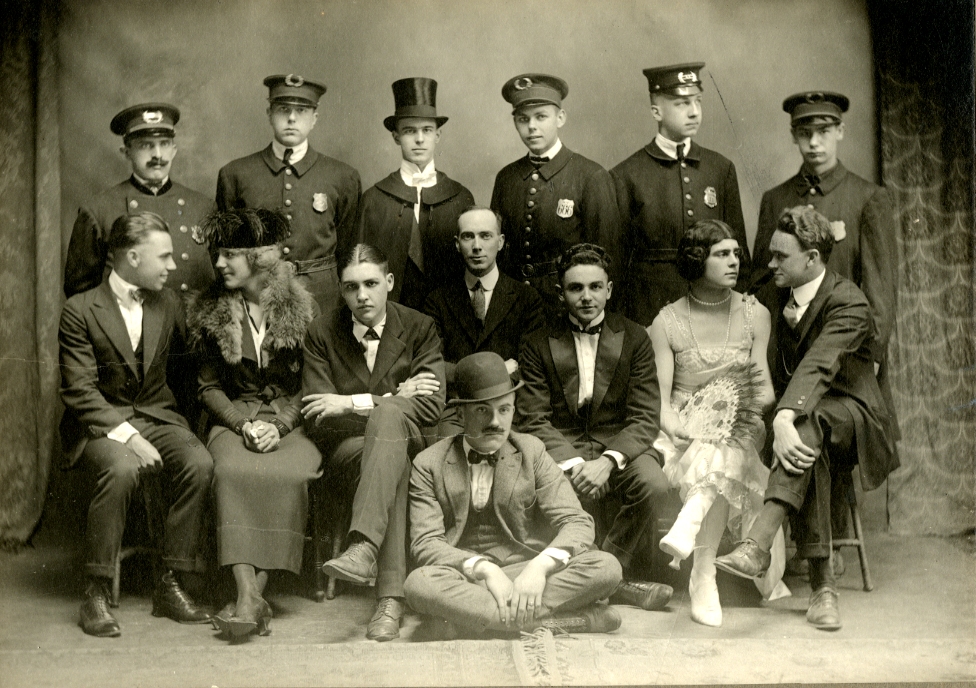

Officer 666, written by Augustin Machugh and produced by George M. Cohan, had enjoyed a decent Broadway run of 192 performances in 1912. It featured a convoluted plot based on mistaken identity and wild coincidence, concerning an art collector posing as a policeman, who just might possibly have demonic qualities. It was the sort of thing sure to please, especially if done well. Smith and his cast were committed to that, so much so that in the remarkable cast photograph, no one broke character, even the men playing women’s roles.

Thrilled with their success, Smith’s company plunged forward. A year later, The Log reported that “beginning without a penny, in two years the Dramatic Club has, by its own efforts, produced eleven plays, purchased two sets of scenery, and started a bank account. It looks toward the future with hopes of bigger and better things.” Smith’s selections for 1920-21 included Grace Furniss’s three-act comedy-drama, The Man on the Box, and two evenings of one-act shows, one of which, Toys, he had written himself.

Exit Smith, Enter Boardy

Laurence Smith left Williston in 1921, but dramatics were placed in the capable hands of Howard G. Boardman, who arrived the following fall. “Boardy,” as he was universally known, was at the beginning of an extraordinary career. Over the next 40 years he taught French, coached soccer, headed Ford Hall, served as Senior Master, and especially distinguished himself as director of the Theater and as Alumni Secretary. In the last role, during the Second World War, he wrote long, personal letters to probably hundreds of alumni serving around the world, letters that many alumni recalled as links to a familiar sanity in the midst of chaos. It is impossible to understate his significance to Williston history.

Boardman essentially picked up where Smith had left off. He told The Willistonian that he liked the idea of presenting a group of short plays in the fall; actors could gain experience, while he had the opportunity to assess where their strengths lay. This would inform his selection and casting of a full-length play for the winter term. He also employed a faculty colleague as his assistant, who would stage some of the small productions and co-direct the large ones. For Boardman’s first decade, his assistant was Sumner C. Cobb, who had significant acting and directing credentials himself. Shared responsibility allowed both men to appear in their own shows. Their first large production, in 1922, was an 1890 English farce, Jane, by Harry Nicholls and William Lestocq. For the first time, Boardman and Cobb took the show on tour, opening in Southampton before playing to a packed Easthampton Town Hall a week later.

Much of the fare in the early years consisted of farce and melodrama. Detective plays were popular, as was anything that involved pirates.

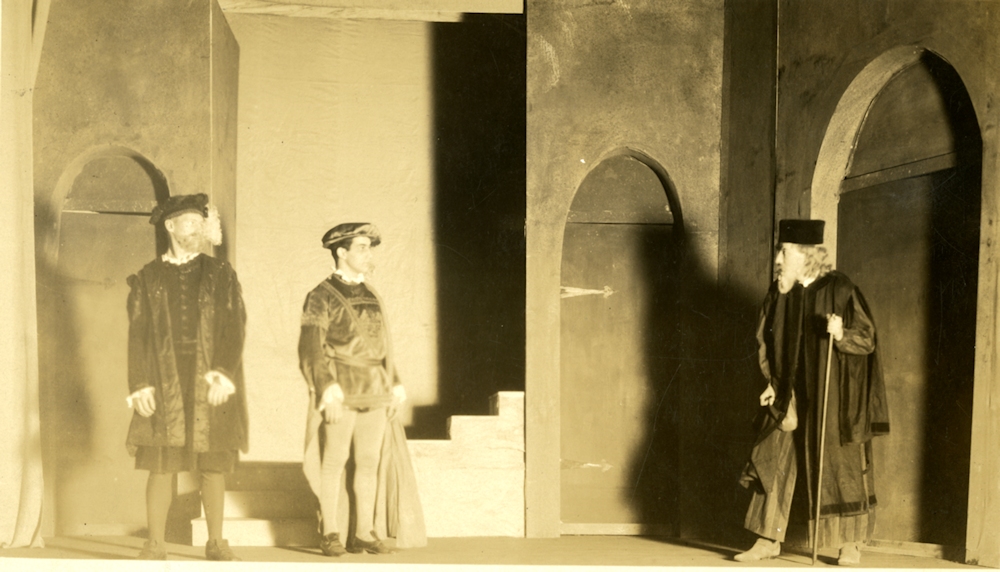

But Boardman aspired to something higher. Convinced that his students could rise to the challenges of serious drama, in 1930 he chose something especially difficult and controversial: Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice, a script which gives producers and scholars pause even today. Boardman took on the role of Shylock himself. (This was, incidentally, the first instance at Williston of female parts being undertaken by women.)

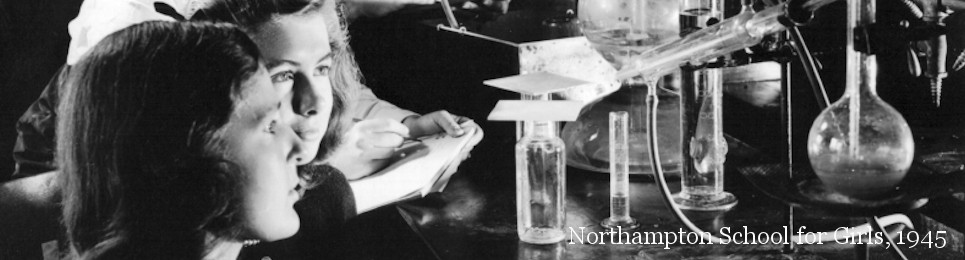

Introducing women into the company was an isolated case. Normally, boys with unchanged voices, or who were accomplished falsettists, took on female roles well into the 1940s, especially in the one-act plays. All the parts in a 1929 show, Joint Owners in Spain, were female, and all played by males. So was the title role in 1922’s Jane, acted by Stuart Pike ’23, who also lettered in football and was a star of the debate team. But Headmaster Galbraith and Northampton School for Girls Principals Sarah Whitaker and Dorothy Bement were actively seeking opportunities for the schools to cooperate: a dancing class, joint Glee Club concerts. In December, 1935, members of Northampton School’s Mask and Wig Society joined the Williston players in Wurzel Flummery, a comedy by Winnie-the-Pooh author A. A. Milne. Sadly, we have no photographs.

Northampton School students would join the Williston Glee Club for a performance of Gilbert and Sullivan’s Trial by Jury in May, 1939. Joint productions of Gilbert and Sullivan operettas took place nearly annually until 1961. Northampton Mask and Wig members rejoined the Williston Dramatic Club for excerpts from The Merchant of Venice in 1936, but annual cooperation did not begin until Out of the Frying Pan, in 1942 (pictured further up the page). 1943’s production of Gold in the Hills was cancelled because of a measles quarantine, but in 1944, the girls returned for Kaufmann and Hart’s comedy, You Can’t Take it With You. With few exceptions, the two schools performed together at least annually, and sometimes more often, until they merged in 1971.

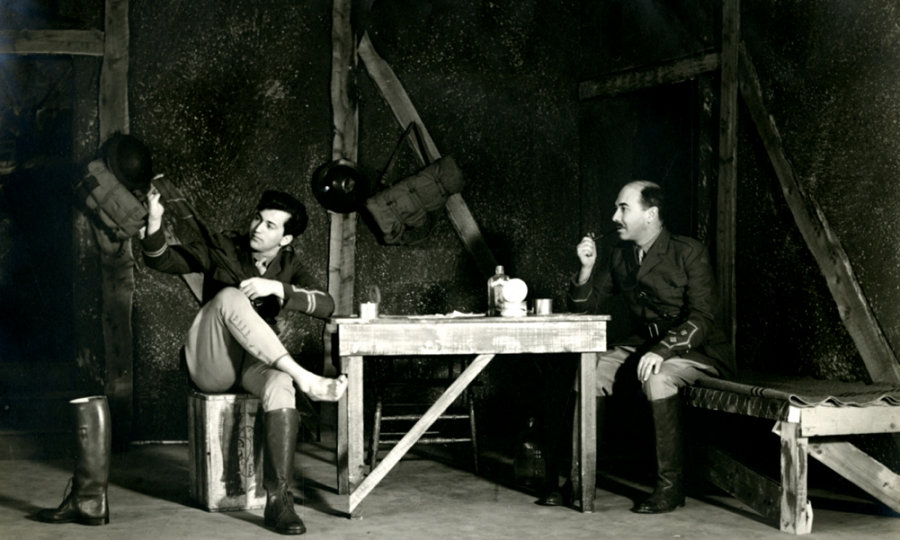

Along the way, there were significant milestones. The construction of the Recreation Center (today’s Reed Campus Center) in 1930 took productions out of the Town Hall, to a portable stage in the basketball court. There were occasional returns to the Town Hall, though; The Pirates of Penzance, pictured above, was one. Boardman’s commitment to serious literature led to an elaborate production of the World War I drama Journey’s End in 1935. It was so successful that Boardman revived it in 1940.

In 1938, with German and Italian fascism threatening all of Europe, Boardman chose a controversial bare-stage, modern-dress production of Julius Caesar that alumni still talked about decades later. Boardy played Cassius.

Space, and perhaps the reader’s patience, limits how much more we can present. There were many successes, including Our Town in 1947 and again in 1956; Arsenic and Old Lace, 1950; Ladies of the Jury, 1953; The Taming of the Shrew, 1954. It should also be noted that Boardman’s productions of one-act plays created opportunities for budding directors and playwrights, including Richard Alpert ’48 (Baba Ram Dass) and Robert Gardiner ’50, as well as faculty authors Laurence Smith and Robert Burdick.

Transition

In 1957, Howard Boardman was joined by a new Assistant Director, Ellis B. Baker ’51, who had, after appearing in Boardy’s plays and on the Middlebury College stage, acquired significant theatrical credentials. At the time Baker arrived, Williston was constructing a science and theater building, present-day Scott Hall, which promised a modern stage and auditorium. The final production in the basketball court was Sabrina Fair, in 1958. Many commented that Baker’s set and light designs brought a fresh new look to Williston productions.

Boardy’s last show before retirement was the first in the new hall, which was dedicated as the Howard G. Boardman Auditorium. (In this writer’s opinion, the name should be restored to general use.) Robert E. Sherwood’s Idiot’s Delight was received with enthusiasm, notwithstanding some good-natured ribbing about the title — perhaps not so good-natured from insiders who discovered certain acoustic limitations to the building. Ellis Baker, following Boardman tradition, was in the cast.

So Howard Boardman retired, leaving the theater program in Ellis Baker’s capable hands. Baker saw possibilities for theatrical ventures of a seriousness and intensity rarely encountered in secondary schools. A new era, a golden age of Williston dramatics, was on the horizon.

Awesome piece. Where’s the next chapter?

Thanks, John — it’s not yet written!