Early Coeducation at Williston Seminary

September 2021 will mark a true milestone in school history: exactly 50 years earlier, Northampton School for Girls and Williston Academy, newly merged, opened as the fully coeducational Williston-Northampton School. That story is told elsewhere (see Northampton School for Girls – and After). It wasn’t always an easy transition – a few years later, according to legend, the hyphen was legally dropped from the school’s name after a highly placed administrator, in an ill-timed jest, suggested it represented a minus sign. Times have changed, and we are preparing to celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of coeducation at Williston Northampton.

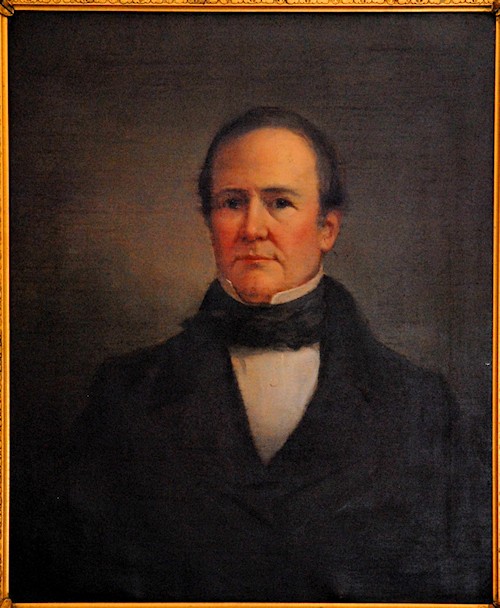

Few, perhaps, are aware that in 1841, 130 years before the merger, Williston Seminary had opened as a coeducational school. Part of Samuel Williston’s motivation for founding the Seminary was that Easthampton had no high school. Poor eyesight had forced him to curtail his Andover education, and Williston, already on the road to becoming Easthampton’s principal municipal benefactor, must have wondered whether, had there been educational opportunities closer to home, things might have been different. Williston was also acquainted with the great Massachusetts educational reformer Horace Mann, a pioneering advocate for the education of women. (For biographical information on Samuel and Emily Williston, see “The Button Speech.”)

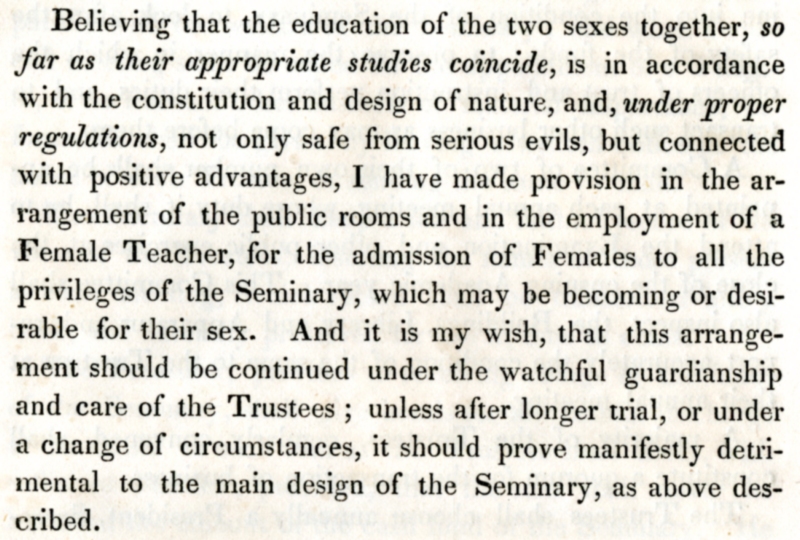

There are suggestions, though, that from the beginning, Samuel had misgivings about coeducation. His original inspiration had been the great English public (i.e., private) schools, notably Rugby, all of them bastions of maleness. The bylaws of Williston Seminary, published in 1845 but in effect from incorporation, stated,

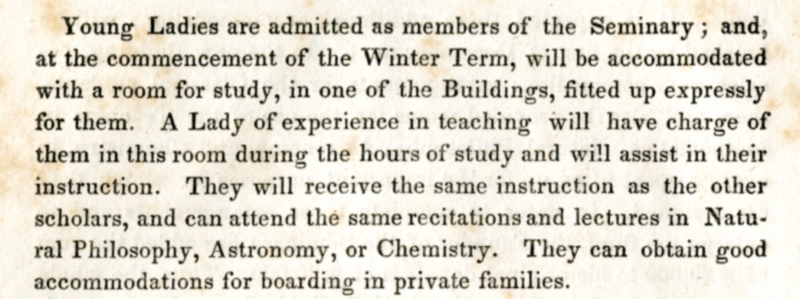

When classes first convened in December 1841, there were 192 scholars, 53 of them – 27% – young women. The Seminary’s literature made it clear that young women had access to all the curricular resources of the school. The Annual Catalogue of 1844 notes,

So far, so good. But as the passage specifies that young ladies might attend the lectures in the sciences, it implies that the “same instruction as the other scholars” was taught separately by the “Lady of experience,” regardless of the subject matter. The “Lady” in question in the earliest years was one Miss Clarissa Stacy, listed in the Catalogues as “Teacher of the French Language.” In 1844 she was joined by Miss Sarah Brackett, who had the grand title of Preceptress. More often than not, over the next two decades of staff changes, the French teacher and the Preceptress were the same person. But only rarely did the Catalogue even acknowledge that individual as Preceptress, This was the case even in 1849-50, when Samuel Williston’s adopted daughter, Harriet Richards Williston held the job. Harriet, class of 1847, had no college education, having enrolled briefly at Mount Holyoke but withdrawn. Before becoming Preceptress, Harriet had also taught French, which she’d learned from Miss Stacy, from 1847-49.

In all but two instances we do not know the educational backgrounds of the nine women who served as Preceptress between 1844 and 1863. Besides Harriet, two others were recent alumnae of the Seminary. But it appears that the Preceptresses, occasionally assisted by another teacher, were responsible for every facet of the girls’ education outside the sciences, regardless of qualifications. This certainly calls into question how seriously the Seminary took its claim of “the same instruction.”

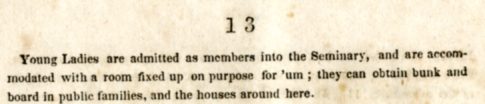

The special accommodations for girls appear to have sufficiently impressed male students to the point where, in 1846, a wickedly accurate parody catalogue included this passage:

If the tone of the preceding seems just a tad condescending, it may not be accidental. As we have noted, there is evidence that the Seminary’s commitment to educating girls was not all it might have been. “Separate but equal” may have been upheld to the point of invisibility. First of all, one cannot help but notice that among the many surviving archival letters from male students of the Seminary’s first three decades, the girls’ presence is barely mentioned at all. In a September 1842 letter home, Albert Montague wrote, “There are about 130 scholars counted with the Seminary and nearly 40 of them are handsome misses.” And for the next twenty years, that is very nearly all. (For a full transcription of Montague’s letters, which are the Archives’ earliest student documents, see “Not Homesick in the Least.”)

In fairness, it is difficult to guage the rigor of the academic demands made on either young women or men. The classroom of the 1840s and ‘50s was very different from what we might expect today. Students gathered in large halls, where they heard lectures, or “recited.” That entailed being orally quizzed by the Professor, in front of everyone in the room. The Professor was often not a specialist, but would drill his charges equally in Latin and Mathematics. In some schools there was not even division by grade level or attainment; Williston Seminary, at least, put its (male) seniors, middlers, and juniors in different rooms. It was a carryover from the old one-room schoolhouses of the previous generation. This model did not change much until the 1860s. So it is possible that Williston’s Preceptresses were genuine polymaths. The quality of education may have been better, or at least evolved to something better, than was originally implied.

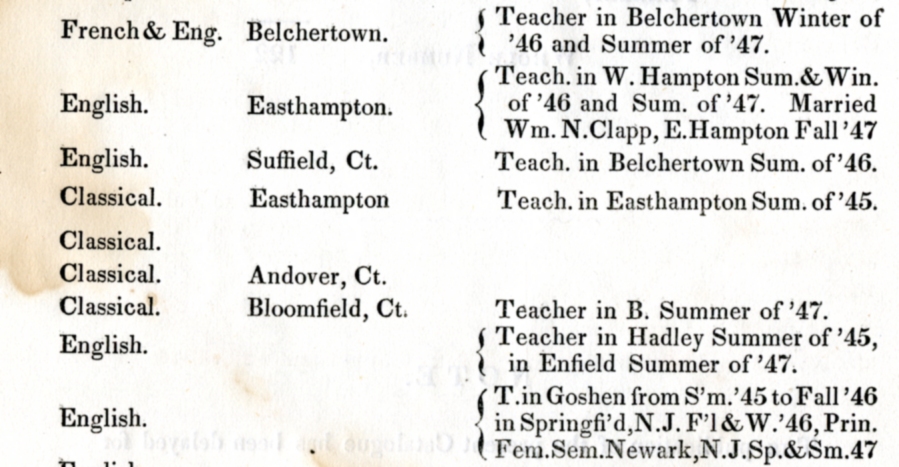

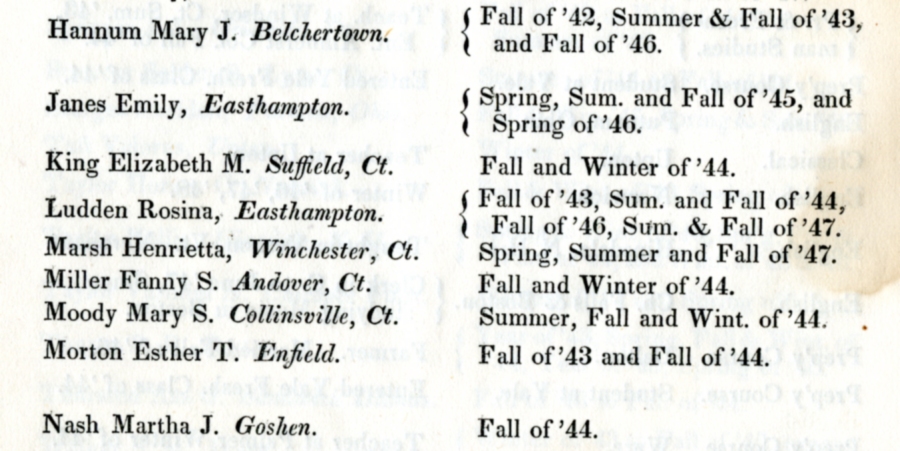

And we have an encouraging piece of anecdotal evidence. In 1844, almost before the ink was dry on the first set of diplomas, a group of alumni organized something called the Memorandum Association of Williston Seminary, “to obtain and perpetuate facts, for mutual gratification, relative to its members.” They even engaged the ubiquitous Clarissa Stacy as their secretary. In 1845 and 1848 they published a “Catalogue” – what amounted to Williston’s first alumni directories. Of the 14 (out of 82) female contributors to the first edition, five identified themselves as schoolteachers. The proportion of teachers was even higher in the 1848 compilation: of the 28 women who responded (out of 122 alumni), 17 were teaching and two were Preceptresses, one of them at Williston. There is a tradition that good teaching begets future teachers. One would like to think this is an example. (Alas, the Memorandum Association never published another directory after 1848.)

In the Archives, there are almost no records of individual women students from this period. Academic transcripts for any students, male or female, prior to 1873 do not survive, or perhaps never existed in that format. While the Archives have retained or obtained a reasonably substantial selection of letters, journals, and scrapbooks formerly belonging to males, from young women, we have identified only three.

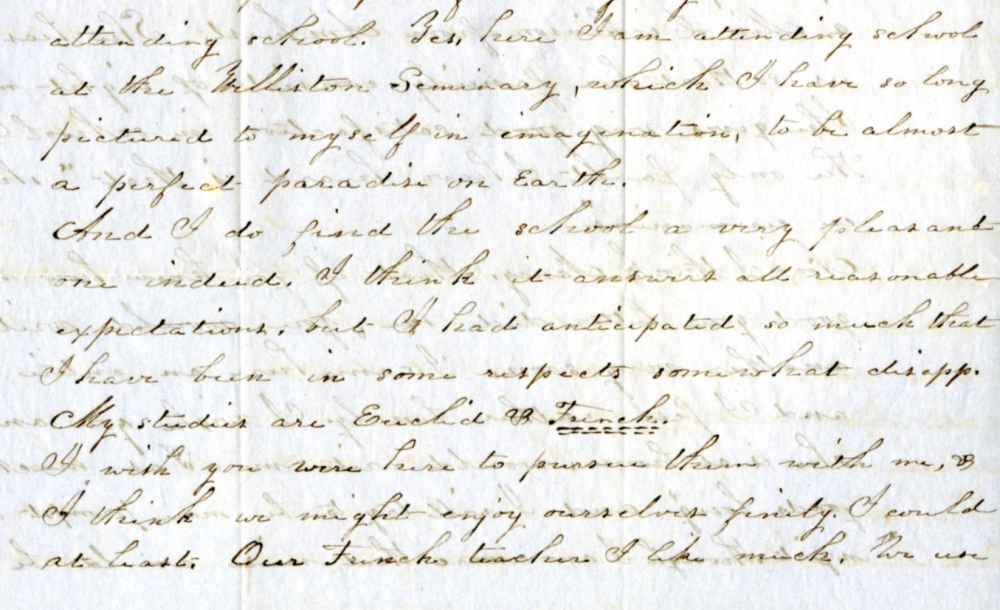

The first is a bit of an enigma. We know the writer only by her initials, “A. J. G.” She is writing in March, 1846, to a Miss A. H. Hubbard in North Amherst, Mass. She writes, “Yes, here I am attending school at the Williston Seminary, which I have so long pictured to myself in imagination, to be almost a perfect Paradise on Earth.”

She continues, “And I do find the school a very pleasant one indeed. I think it answers all reasonable expectations, but I had anticipated so much that I have been in some respects somewhat disappointed. My studies are Euclid & French. I wish you were here to pursue them with me, and I think we might enjoy ourselves finely. I would, at least. Our French teacher I like much. We use Bugard’s French translator. Euclid I think is very difficult, but I am exceedingly interested in it.”

Elsewhere in the letter the writer invites Miss Hubbard to visit her at home in Brookfield, Mass. But it is impossible to further identify the author. The student rosters in the school Catalogues for 1846 and the adjacent years list no one with those initials, and no young women from Brookfield. Perhaps A. J. G. did not stay long enough to have her name printed in the annual rosters.

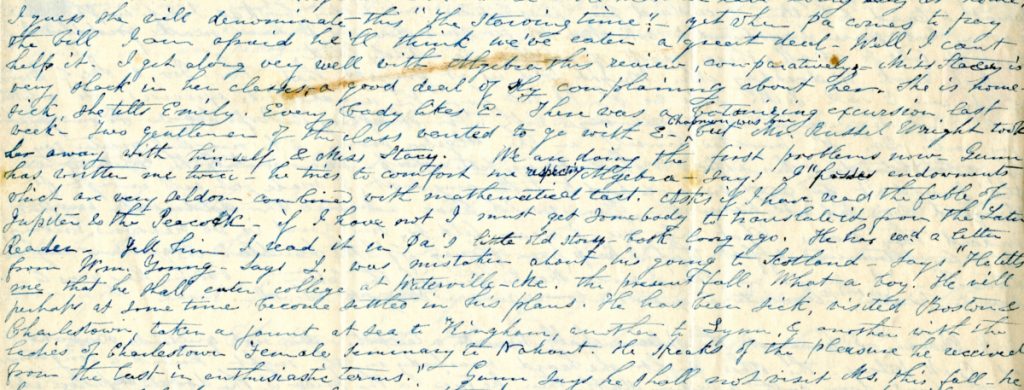

Another letter is a joint missive from sisters Urania and Emily Stoughton, class of 1845, to their family in Gill, Mass, postmarked August, presumably 1844. Most of the letter is in Urania’s tiny handwriting – she can be identified because she refers to her sister by name. As for Emily, her penmanship is so challenging as to be largely illegible. Where “A.J.G.” is restrained, Urania’s personality jumps from the page. She writes about boys, food, boys, classes, food, and boys. Her sentences are practically breathless: “I wrote so much (my dear Pa) with Fred standing at our door trying to make Emily come out into the space – he brought his coat to mend and I told him, the last time he was here, he should not come to our room any more – if he came to see E- again, they should sit on the stairs – She told him he should come in, I told him he shouldn’t, & he declared he wouldn’t unless I went out. Told him I must write a letter – said he had something to tell E- that he shouldn’t tell me at any rate & she refusing to go into the space. I told him finally I would go down for a cent, so he gave me a cent and I am down here. Miss Brackett [the Preceptress] talks so much to us about associating with the young men, that we know there is, in reality, no harm in Calvin’s and Fred’s coming to our room, yet it might make a great stir if it happened to be known & I can’t bear the thought.” [Urania appears to assume her family knows who these young men are. Fred is probably Frederick Tenney, also of Gill; Calvin may well be Calvin Locke, from nearby Hinsdale, N.H.]

Elsewhere, Urania writes, “Miss Stacy is very slack in her classes. A good deal of sly complaining about her. She is homesick, she tells Emily. Every body likes E-. There was a botanizing excursion last week. Two gentlemen of the class wanted to go with E- (Chapman was one), but Mr. Russell Wright took her away with himself & Miss Stacy.” [Russell Wright taught Latin, Greek, English grammar, and botany. Plant-collecting expeditions were a popular activity that allowed chaperoned couples to spend time together, under the guise of scientific study; for a slightly later example, see Botanizing.]

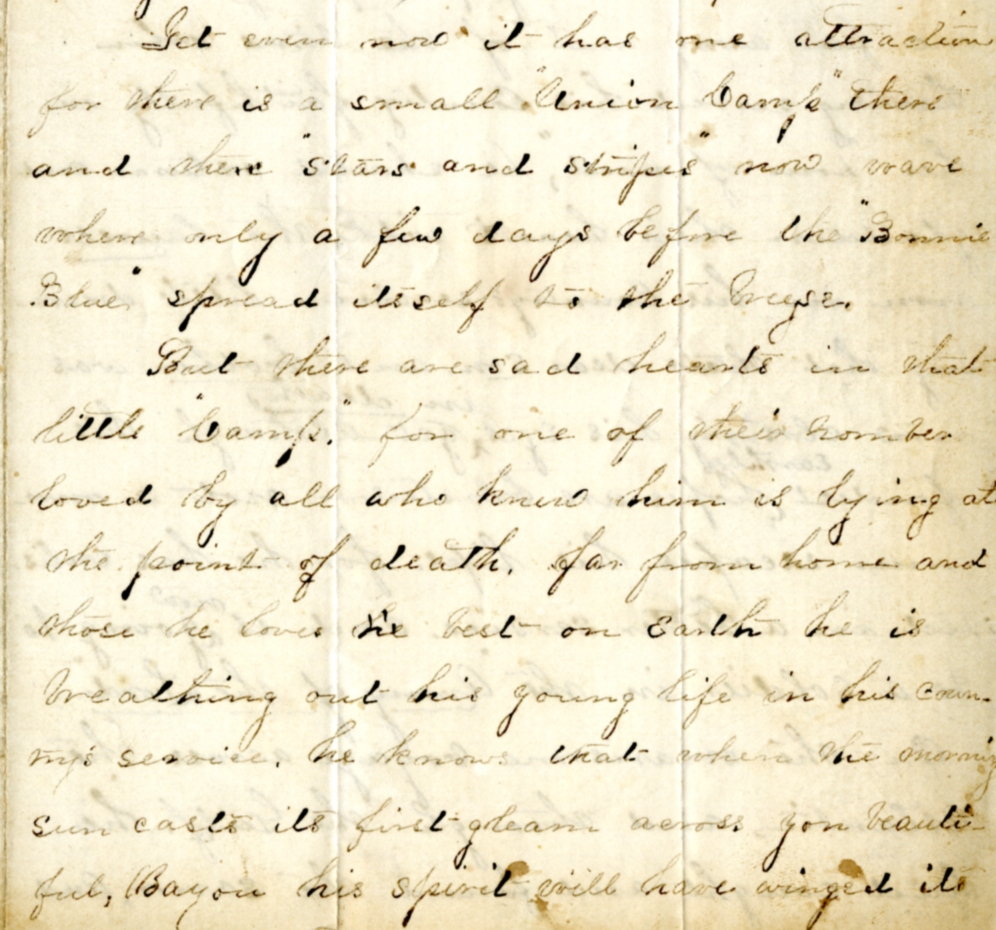

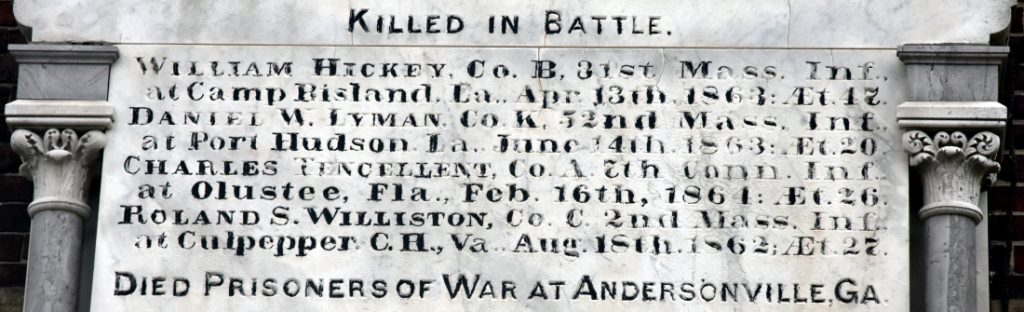

We move ahead nearly two decades, to an essay, entitled simply “Composition no. 2,” by Belle (Isabel Pamelia) Clapp, class of 1864. Belle writes of a Union cemetery somewhere in the South, near the banks of the Mississippi. “But there are sad hearts in that little “Camp,” for one of their number loved by all who knew him is lying at the point of death. Far from home and those he loves the best on Earth he is breathing out his young life in his country’s service. He knows that when the morning sun casts its first gleam across yon beautiful Bayou his spirit will have winged its way far upward to the “land of rest” where there is no more parting and where the clashing of arms and the din of battle is not known, and his mind wanders far away o’er land and sea to his own New England home, and in vision he enters the old farm house and sees Father, Mother, Brothers and Sisters seated around the fireside and talking, perhaps, of the loved one far away and of the time when having served his Country faithfully in his “hour of need,” he should return and gladden their hearts with the Laurels won in his country’s service — little dreaming that their dear Son and brother was now closing his eyes in death. Yet — although fondest earthly hopes are blasted — not a murmur escapes his lips, for he has enlisted in a better service, and is now going to be a soldier in the ‘Army of the Lord.’”

Almost laughably, this document contains every cliché imaginable — until one realizes that Belle means every word. She brings it home: “I think not my dear schoolmates that this is a mere fancy sketch, for it is alas, true of one, who has walked these same classic halls and who was held dear in the hearts of many of the people of Easthampton.” She is almost certainly referring to Daniel Watson Lyman, class of 1859, killed at Port Hudson, La. June 14, 1863.

It is no surprise that we have no contemporary photographs of Williston Seminary women prior to the 1860s. Portrait studios were just catching on at the beginning of that decade. The Archives hold an intriguing set of photographs extracted from an album assembled by Frank Moore, class of 1863. The donor, a descendant, sent us those images that were identifiable as Williston students, or which might have been, based on the age of the subjects or the location of the photographer. Portraits of several young women are included, but they are not identified by name, so it is impossible to tell whether they attended Williston. There is one exception: Mary Jane McKinlay, class of 1863, of whom there are several images, some with her sisters. There is also a single intriguing photograph of a more mature woman, taken at a Northampton portrait studio. While there is no way to be sure, it is possible that she is Elizabeth B. Hinkley, Preceptress from 1855 to 1863.

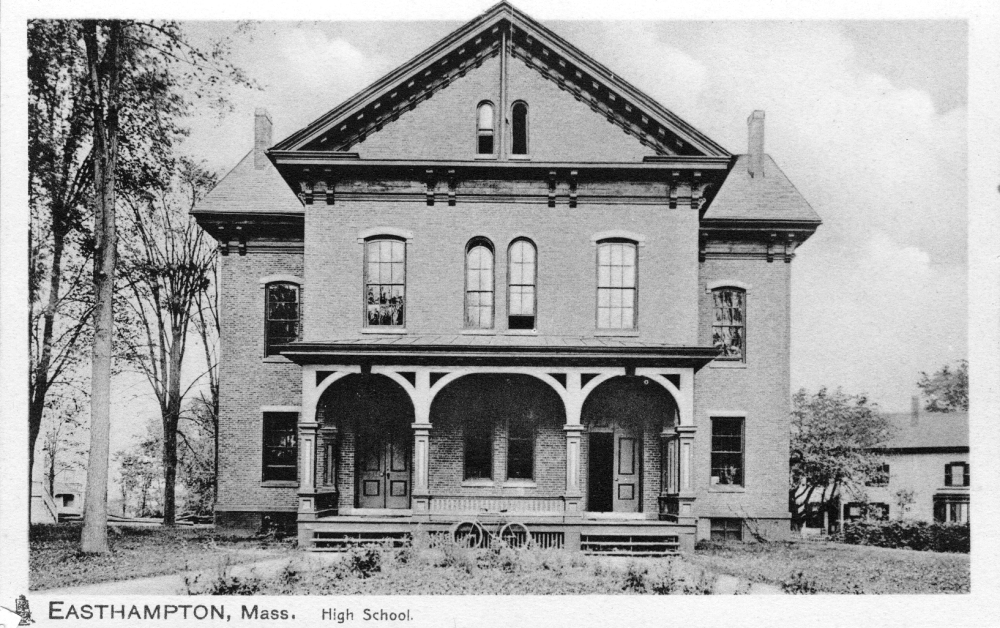

1863-64 was the last year of Williston Seminary coeducation. Samuel Williston, awash in profit from his wartime textile manufacture, acted on a longtime promise to build a public high school for Easthampton. What remains today as Easthampton’s Memorial Hall stood at the northern end of Main Street, adjacent to the Seminary campus. Williston’s last Lady Preceptress, Elizabeth C. Chapin, who served in that final year, was installed as Principal of the new school.

Miss Chapin is worth a few words, since aside from Harriet Richards Williston, she is the only one of Williston’s Preceptresses whose background we know. She was an 1854 graduate of Mount Holyoke, who taught in Rome, N.Y. and Amherst, Mass. before coming to Williston. Many, including colleague and future Headmaster Joseph Sawyer, have written of her as an creative, innovative teacher and inspiring role model. In other words, in apparent contrast with the early Preceptresses, she was highly qualified. The same can probably be said for her predecessor, Elizabeth Hinkley, whose eight-year tenure was the longest of any. Elizabeth Chapin went on to a lengthy and distinguished career in the Easthampton schools, until her death, aged 66, in 1901.

But behind the civic obligation that inspired Samuel Williston to underwrite the new public high school, there is an underlying sense that he had never been comfortable with coeducation. He was, after all, a creature of his times, a socially conservative one at that. He was committed to the education of women; his and his wife Emily’s financial support had helped Mary Lyon found Mount Holyoke. And he was quick to acknowledge that Emily was his equal in intellect and just-plain-wisdom. But his social upbringing suggested that the sexes shouldn’t idly mingle; if nothing else, they distracted one another, sometimes more. There may have been other, more specific concerns. Urania Stoughton’s mention of the attention teacher Russell Wright paid to her sister Emily is sufficient to raise at least one eyebrow. And from 1857-59 Samuel Williston’s niece Hannah More Williston attended Williston Seminary. In her second year she became acquainted with a young teacher, George Bishop, right out of Amherst College. Suddenly Hannah found herself finishing her senior year at Grove Hall in New Haven. Shortly thereafter Mr. Bishop left to study theology at Princeton. Four years later, Hannah and newly ordained George were married. Of course, this is all utterly circumstantial – but is that other eyebrow raised?

In the end, according to Joseph H. Sawyer’s Alumni Record of Williston Seminary (1874), 1,077 young women attended Williston Seminary before coeducation ended in 1864, representing approximately one-fourth of the total number of students. From this point forward, Williston would remain strictly a men’s institution. Well, not quite. Girls from Easthampton High would occasionally enroll in subjects not offered in the public school – advanced Greek, for example. In the 1930s, Williston began to cooperate with Northampton School for Girls in a number of social, musical, and theatrical efforts. But the faculty remained entirely male for 95 years, until 1958, when this writer’s mother, a former Northampton School Latin teacher and current Williston faculty spouse, was invited to join the staff. This was at the instigation of Williston Trustee and Amherst College President Charles Cole, who suggested to Headmaster Phillips Stevens that a fine classicist, one who had taught his daughter, was underutilized serving refreshments at postgame athletic teas. Lorraine Teller joined the Latin Department – and went on pouring cocoa after football games. That may be among the reasons she, and another faculty spouse engaged to teach French, Irene Couderc, were lured away to rejoin the Northampton School faculty a few years later.

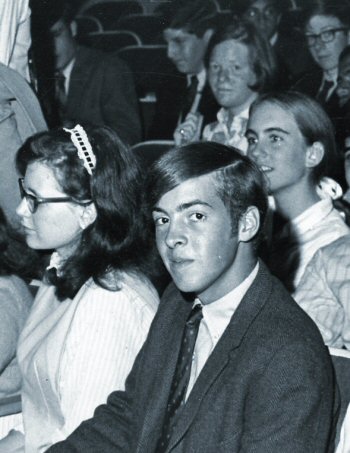

By around 1966, Phillips Stevens and the Williston Board were convinced that coeducation was part of Williston’s future. It was a controversial idea, largely (and for too long) kept under wraps, even though Williston and Northampton School students soon began to appear in one another’s classrooms on a limited basis. (Once again, see Northampton School for Girls – and After.) In 1967 Stevens offered enrollment to the daughters of Williston faculty members. Several families took him up on it. But several others pointedly did not, preferring to send their daughters to Northampton School, MacDuffie, or Easthampton High. Coeducation remained a controversial idea within Williston culture.

All that, of course, would need to change following the merger with Northampton School in 1971.

My thanks to Deborah Richards, College Archivist at Mount Holyoke, for providing certain information for this article.

Good job on this Rick. As I was reading the article, I remembered that you went to Vassar where I’m pretty sure you were one of the first males at that institution. Couldn’t help thinking that this subject matter was an excellent match for you.

Thanks, Alan. That’s funny, because since most of the article concerns the mid-19th century, Williston-Vassar parallels weren’t on my mind at all during the writing process. But during my freshman year at VC (1970-71, the last year prior to the Northampton/Williston merger), it was clear that not everyone there was fully enthusiastic about coeducation. Vassar, like Williston Northampton, underwent some pain during the transition. Most, including myself, believe that both schools, by emphasizing and building on their best traditions, emerged from the period with new, as well as pre-extant, strengths.

This is such an interesting article, Rick. Enjoy your retirement, but please keep the blog posts coming.

Rick, this a terrific article! Congratulations and thanks.

Happy retirement! Thank you for this article. It will be a good year to visit the school if the pandemic permits. Sincerely, Susan Andrew