Each fall Archivist Rick Teller ’70 speaks to the assembled School on some aspect of Williston Northampton history. The event, popularly known as “the button speech,” only occasionally concerns buttons at all. But this year it did. These remarks were delivered on Friday, September 20, 2013.

Good morning. At solemn occasions … like hockey games … we sing about someone named “Sammy.” Our hearts yearn for him … for his campus and geriatric elm. But, you might well ask, about whom do we sing? Just who was “Sammy?”

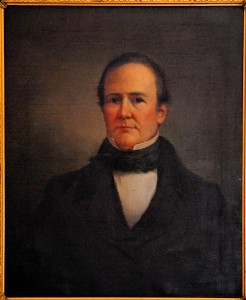

Samuel Williston was born across the street, in a house located where the Homestead now stands. The house, where Mr. Swanson lives and which we now call “The Birthplace,” was moved across Park Street in 1843. It is much grander now than it was when Sam arrived.

That was in 1795. George Washington was President. Easthampton was a small farm village. Samuel’s father, Payson Williston, was the minister in Easthampton’s only church. Payson was a stern, old-fashioned New England preacher, with strong Calvinist leanings. We will get to Calvinism in a minute. The Reverend Mr. Williston’s salary was tiny, and he had a house full of children. He added to his income by planting a few acres of mediocre farmland. That farm is now the heart of our magnificent campus.

Young Sam grew up with religion and the work ethic all around him. It may have been an austere childhood, but it was hardly confining. Payson Williston, a Yale graduate, and Samuel’s mother Sarah valued learning and ideas. Early on, Samuel assumed he would follow his father’s footsteps to Yale, and eventually enter the ministry. Admission to Yale, then as now, required an education of substance. That presented a problem. Easthampton had no schools. Sam was taught by his parents, and later by the minister in Southampton, and briefly attended a small academy in Westfield. He gained a decent, if fragmented, education, but it came second to farm work, first, at age 10, at home; later at a nearby farm, where he was able to earn a few dollars for his family.

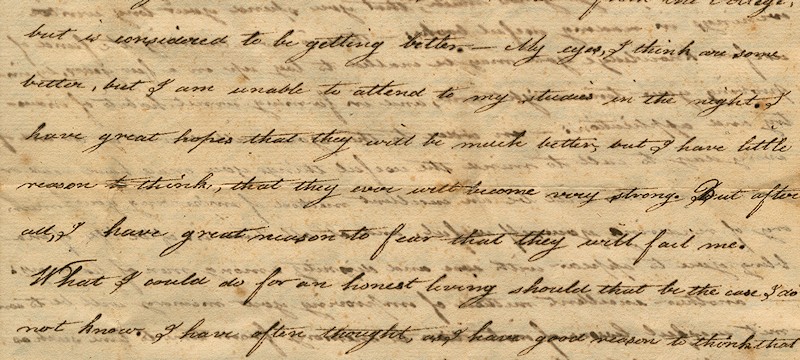

At 19, he took advantage of an opportunity to attend Phillips Andover, which offered scholarships to the sons of clergymen. At Andover Samuel lived with a family in the village. To earn his keep he did farm chores — pitching hay, chopping wood, and so on. His daytime work meant postponing study until after dark. Candles were expensive, so Sam worked by the light of a single whale-oil lamp. It produced more glare than useful light.

Samuel had been at Andover for only one term when he became concerned that his eyes were failing. Poor eyesight ran in the family. He consulted doctors, who had no help to offer. That may actually have been a good thing, considering that the medical practice of the day often did more harm than good. It became apparent that he could not continue his studies, so he returned, disillusioned, to Easthampton.

Before long he was in Springfield learning the storekeeper’s trade with a family friend. Business seemed to suit him. He learned a few things about sales, and hard bargaining, and managing money. Eventually he took a job in New York with another family friend, Arthur Tappan, and continued his hands-on business education. That ended suddenly in 1817, when the economy forced Tappan’s business to close. Sam returned home, still wondering, at age 22, what he might do with his life.

Not long after this, he met Emily Graves, the daughter of the minister in Williamsburg, just north of Northampton. Emily was as serious-minded as Samuel. Sam’s father, no fool about these things, brought them together. But in an age when arranged marriages were common, Samuel and Emily just happened to be ideal for one another. They were soon engaged, although the wedding would not take place for another five years. Samuel insisted on achieving some measure of financial security before committing himself to marriage. He scraped together a little money to expand the family farm, and raised sheep where we now play football. Sam saw possibilities in getting in at the start of a New England wool industry, which could compete with expensive British imports. He had also never lost his interest in education, and found that despite his poor eyesight he could teach a little in the winter, when the farm needed less attention.

In May of 1822 he and Emily were finally married, in a simple farmhouse service in Williamsburg. Emily wore a black silk wedding dress, the first silk garment ever owned by any member of her family.

The wedding was the beginning of a spectacular partnership. Do you have an image of the submissive nineteenth-century housewife? Not Emily, who was clearly Samuel’s equal in both intellect and will. Sam knew it, and he cherished it. Throughout their long marriage, they would consult one another on every business or charitable venture. More to the point: to save Samuel’s bad eyes, Emily would read to him and frequently wrote for him. She knew virtually everything he did. They would prove to be an ideal combination of a man of vision and a woman of practical means, not without vision of her own.

One of the great success stories of the 19th century begins with the most mundane, insignificant item imaginable. Can you see this? Yes, it’s a button.

In an economy partially based on barter, Emily, like many local women, earned a little extra money with needlework. Her specialty was making fancy cloth-covered buttons, a intricate process in which a circle of cloth was sewn around a wooden disk. She’d learned this from her mother.

In 1823, the Willistons had a visitor. Emily noticed that on his coat there were buttons of a type she had not seen before. She couldn’t resist. In the dead of night, while the rest of the household was asleep, she removed a button from the coat, carefully took it apart, figured out how it was made, reassembled it, and sewed it back on. The guest left the next day, unaware of his role in your history.

OK, pause. Those of us who attended Williston Academy any time between around 1870 and 1970 cut our teeth on this story. It is part of EMILY WILLISTON, THE LEGEND. One challenge for an historian is to try to separate the good stories from the true ones. Is this one true? Sam Williston used to tell it slightly differently. Joseph Sawyer, who served on the Williston faculty from 1866 to 1919, wrote that he had this version from Emily herself. As one who valued her moral reputation above all else, Emily would not easily have admitted doing something downright sneaky. So in this instance, there appears to be some truth to the tale.

In any case, Emily practiced making the new button until she felt secure with it and then — remember the black silk wedding dress? — she cut it up to make sales samples. Sam offered them to his former New York employer, Arthur Tappan. Tappan’s response was astounding: He offered fifty dollars for 25 gross — that’s 3600 handmade buttons.

Fifty bucks may not seem like much to us now, but to Sam and Emily, it was a fortune. Consider: the most his father had ever earned in a year was $300.00, and he was often paid in firewood and chickens. Tappan paid cash! The Willistons worked out a scheme in which local women were employed at home, making buttons to the new design. Samuel and Emily provided materials, instructions, and transportation. Soon over a thousand households between Springfield and Pittsfield were employed in button manufacture. For the first time in their lives, the Willistons were earning real money. It is an early example of the remarkable business team this couple would make: Emily had ideas, and the practical sense to figure out how to do something. Samuel was ambitious, and could sell.

His talents lay not only in salesmanship, but in an ability to make unusually canny fiscal projections. He was a perceptive market economist at a time when the term had not yet been invented. He could analyze balance sheets and practically predict the future. As the button business grew, he didn’t sit on his cash, but started or invested in other industries, a general store, the railroad, gas lighting, banks, and especially cotton yarn and elastic. He and Emily seemed to be especially lucky, or especially blessed.

But even as they shared success after success, horror struck. For most of us, the loss of a child is unimaginable. Emily and Samuel had four daughters. Not one of them lived past the age of five years. At a time when antibiotics were unknown, infant mortality was common. But — all their children?

With their deeply-held religious beliefs, Emily and Samuel would have turned to God and asked, “Why?” “What can we do?” And for them, God had an answer: Use what has been granted you to do the Lord’s work.

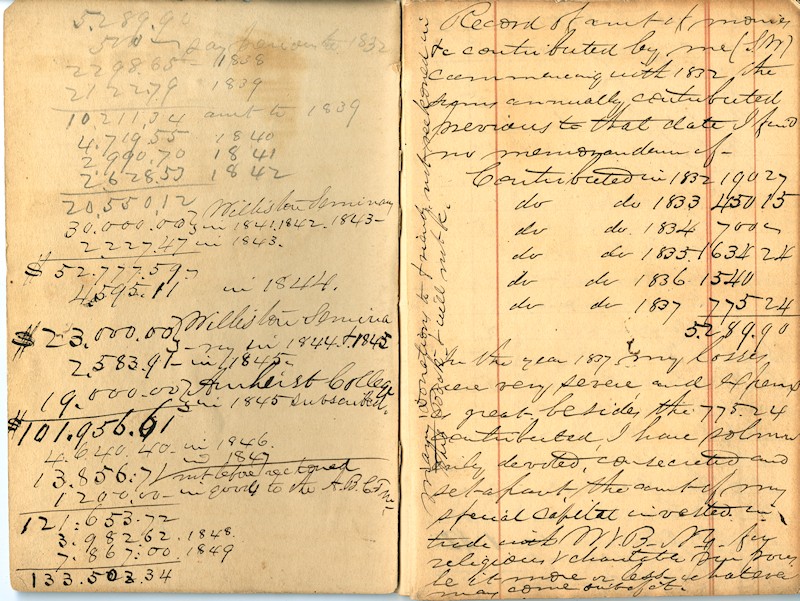

Which they did. If there was a worthy cause, Sam and Emily were there. Foreign missions were important to them. The abolition of slavery. Samuel built a new Congregational church for the growing town. When it burned down, he built it again, and a third time after the steeple fell through the roof in a windstorm. The third structure still stands: the white brick church on the corner of Main and Union Streets. Education — they were passionate about education. Williston money helped get Mount Holyoke College started. When Amherst College neared bankruptcy, Sam bailed them out. The Amherst trustees actually offered to rename the college for him. Sam and Emily, like many Americans in the 1840’s and 50’s, were caught up in the idea that it was the manifest destiny of the United States to expand and develop the western continent. The Willistons, clearly believing that educational institutions were a hallmark of civilized society, subsidized the founding of several colleges on what was then the frontier, including Knox in Illinois, Grinnell in Iowa, and others.

“Doing the Lord’s work.” For many of us, in this secular age, that doesn’t ring true. But let’s return, for a moment, to Williston’s Calvinist background.

Calvinism had deep roots in New England. It was the core of the Puritan faith which had led the first Pilgrim exiles to settle in Plymouth, and which dominated Massachusetts religion and politics during much of the 17th and 18th centuries. As its American version evolved, New England Congregationalism softened its harshest attributes, though not before hanging eighteen innocents during the Salem witch hysteria. It was falling out of fashion by the early 19th century, but for 100 years one of its intellectual homes had been Yale University, which had trained Samuel’s father along with some dozen other Williston uncles and cousins, all highly respected New England clergy.

Calvinism taught that God had a plan for each of us. Your life was determined before you were born. If you were predestined to be a horse-thief — well, so be it. If, however, you were one of the elect, one of those whom God had selected to be saved, then Heaven was guaranteed. But, you ask, what about free will? Was there nothing you could do? How depressing! How fatalistic! No wonder the belief was in decline. Samuel Williston’s grandson marveled that “ a man . . . should be agonized with fear that he was not one of the elect, and that, irrespective of his conduct, he was fated to eternal damnation, yet such was Mr. Williston’s attitude of mind during a large part of his life.”1 One prayed to be among the elect, a recipient of God’s grace. That grace was justified through faith, a faith demonstrated by the way one led one’s life. Now this idea can be interpreted as incredibly arrogant, especially when accompanied by the pose of public piety practiced by the great and would-be-great of the time.

But this is an over-simplification, and an unfair one. For Calvin’s message was that success was granted by God; that material blessings were gifts meant to be enjoyed – and especially, shared. Samuel Williston, having started out literally with nothing, was particularly conscious of this obligation. It would drive his actions throughout his life.

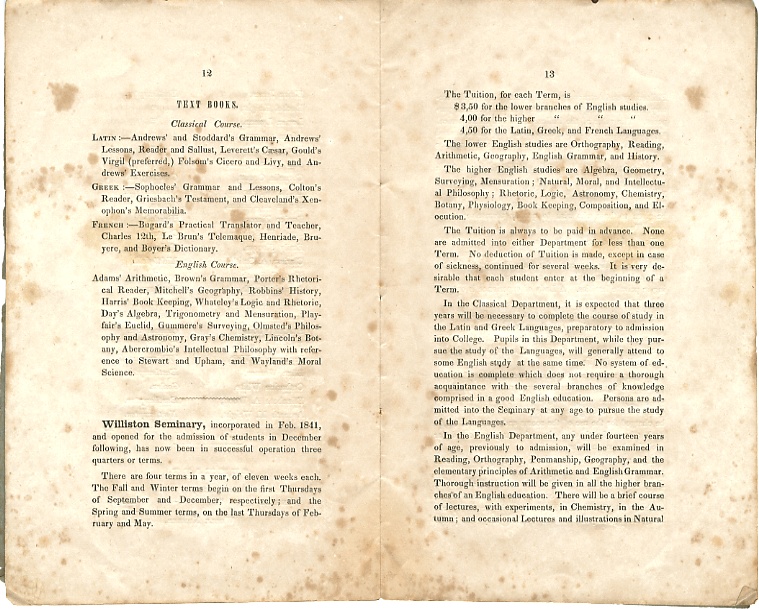

Mindful of his inadequate schooling, Sam proposed a school for Easthampton that would provide two curricula: a Classical Department, in which young men and women could obtain the traditional grounding in Greek and Latin which would prepare them for University and, perhaps, the ministry; and a Scientific Department, in which students who did not plan to go on to college could get a thorough education in engineering, mathematics, surveying — everything needed to enter the professions necessary to build the young nation’s growing industrial base. This was a radical notion in 1841. One can make a case that Williston Seminary was among America’s first technical high schools.

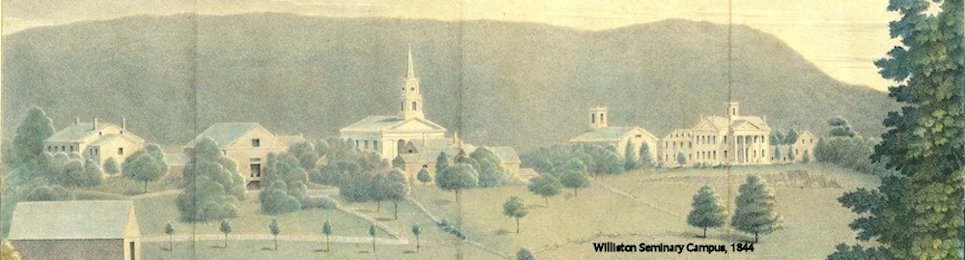

On Samuel 46th birthday, June 17, 1841, the cornerstone was laid for the first Williston Seminary building, on a campus situated down on Main Street, where the banks and Big E’s are today. Incidentally, that cornerstone is now embedded in the foundation of Memorial Dormitory. Look for it.

I’m not going to recite the history of the school today. It thrived. There were some rough decades, particularly after Sam was no longer around to pay the bills. But here we are.

And Mr. and Mrs. Williston — they thrived, too. In New England, towns like Easthampton were rapidly transforming from an agricultural to a manufacturing base. Williston moved his button business from a thousand kitchens to factories in Haydenville in 1831 and then Easthampton – the town’s first — in 1848. Samuel’s grandson recalled a building full of “ingenious machines which struck out and covered a button at a single blow.” The button mill was the first of many factories Sam would build. Many of them still stand. It is at least symbolically significant that our Schoolhouse is a former textile factory. Waves of immigrants were arriving to work in the mills. Easthampton attracted large numbers from Ireland, Germany, Quebec, later Poland. They needed housing, stores, schools, and churches. Sam and his associates saw to it that they were built. As the town grew, so did the Williston fortune. They were inseparably linked.

Notwithstanding their generosity, the Willistons lived in the grand manner. Their mansion — our Homestead — was the finest in town. There are suggestions that Samuel’s aging parents, bred to Puritan austerity, did not approve of such vanity. Samuel was criticized for being “generous with a dollar and tight with a penny.” Inevitably, his success, coupled with a certain patrician arrogance, made him a target for fun — when he wasn’t around to hear it. There are stories, some a little suspect, but too good not to repeat. Sam would drive carpenters mad by walking around construction sites, picking up dropped nails. His business partner, Horatio Knight, claimed that one day he and Sam were conversing in front of the Homestead. When a passing horse did what horses do, Sam, without breaking off the conversation, produced a shovel and dumped the manure in his garden.

In the business world, Williston was a tough customer. While outright dishonesty horrified him, he was a master at taking advantage if he saw an opening. For example: there was a special fabric, made in England, he wanted to cover buttons. The tariff — an import tax — was very high. Making button covers involved punching holes in the cloth. If a few holes were punched by the weaver in England, then the fabric could be imported as rags — no tariff.

During the Civil War, when Southern ports were sealed by a Union naval blockade, Sam needed cotton for his mills. He paid a business associate $60,000 — a huge sum in the 1860’s — to assure a supply, no questions asked. This meant running the blockade. Since Sam’s biggest customer was the Union Army, from which he had a monopoly contract to supply tent cloth and cartridge belts, he could reason that he wasn’t just doing the Lord’s work, it was patriotic!

Yet he had little tolerance for shadiness in others. He had a long and stormy relationship with Charles Goodyear, who had discovered the process for vulcanizing rubber. Before Goodyear’s success he had tried to get Sam to finance a venture which Sam dismissed as a get-rich-quick scheme. Sam had repeatedly turned Goodyear down. In 1848 Sam sought a reliable supply of rubber for a new elastic suspender factory. Someone suggested that he “go after Goodyear.” Williston exploded. “Go after Goodyear? No difficulty in that. To get away from him is real trouble. If he hears of an old lady with ten dollars tucked away in a broken teapot, Goodyear will go after it.”

As Sam aged, and his fortune grew, so did his ego. Emily, who was born with the greater portion of common sense, acted somewhat as a check on this. But Samuel’s investment wizardry had never failed him. He was so confident that he took risks that occasionally scared his partners. If he had a project to finance, whether it was a new mill or a charitable venture, he might strip one of his companies of nearly all its cash, or borrow heavily from the bank. “That’s what banks are for,” he once said, conveniently neglecting to add that he owned the bank, and was moving money from one pocket to the other.

The greater the amount needed, the more likely it was to get his attention, especially if it was for charity. One of his adopted children recalled that if a supplicant was naïve enough to ask for a small contribution, Sam would put on his best farm boy expression and mumble, “I ain’t got that kinda money.” On the other hand, in 1864 the Reverend John Holbrook was in New England seeking to raise $30,000 to endow newly-founded Grinnell College in Iowa. Holbrook told Williston’s friend Samuel Seelye that he hoped Williston would consider giving $1,000. “Don’t bother,” said Seelye — “he won’t even listen.” Holbrook’s face fell. “No, no, you misunderstand me,” Seelye protested. “He’ll just ignore a small request. Ask for the full $30,000.” Holbrook got all of it.

A year earlier Sam had told headmaster Marshall Henshaw that he was discouraged that his Scientific academy was not developing as fast as he had hoped — the actual expression Sam used was “I have often wished the whole thing at the bottom of the sea.” (We once had that printed on a T-shirt.) He intended to cut his losses and close Williston Seminary. But Henshaw knew his man, asked for the moon and the stars, and came away with salaries for three new teachers, and a science lab that rivaled Harvard’s.

In a 1940 memoir, Samuel’s grandson, who spent his childhood summers visiting the Homestead, recalled “a man of imposing presence, who in earlier years must have been notably handsome. . . . I never heard him speak harshly, and I cannot recall that he ever rebuked or corrected me. His manner, however, was uniformly serious if not solemn. . . . That he had softer feelings than might have been guessed from his manner, was indicated by his toleration of young children about the house, as well as by his habit of feeding daily with his own hands the family cat.”

Emily, the grandson wrote, “was the embodiment of gracious dignity . . . a wise woman . . . and not afraid to smile.”

Samuel incurred serious losses in the post-Civil War economic downturn. He made the one great mistake of his life at about this time. His ego got ahead of his judgment, and he invested heavily in a cotton thread mill that was destined for failure. It was the only time in his life he had gone against Emily’s advice. To his credit, he admitted it. By his own estimate, he lost about 60% of his net worth. There’s no real indication of how it affected him, except that the strain may have damaged his health. He consolidated his assets, revised his will, and set his sights forward once more.

His last words in 1874 were “I think I am going through safe.” He was 79. He and Emily had been married for 52 years. She continued their good works, although she had little to do with the school. She took special interest in Mount Holyoke College, and in the Easthampton Public Library, which is named for her. Several writers who knew her have used the word “serene” to describe her last years. The end came in 1885, a month shy of her 89th year. Consider what she and Samuel had lived through: the rise from a post-colonial confederation to a true republic and world power; the industrial revolution; the invention of the railroad, the telegraph, and so much more; the expansion of the country westward across the continent — and perhaps most important of all, the end of the abomination of slavery, and the cathartic conflict that accompanied it.

One day in 1877 Emily and Williston principal James Whiton were riding to South Hadley for a Mount Holyoke Commencement. Emily, in a reflective mood, said to Whiton, “I thank God for the opportunity to do my part in a time of colossal change.”

“I thank God for the opportunity to do my part.” I think that, above all else, sums up Emily and Samuel Williston.

And remember that I mentioned that Sam ruined his eyesight at Andover, in part because of an inadequate lamp? This is the very lamp. You might well ask how on earth we still have it. Well, you know how you save stuff? At least according to legend, Samuel Williston kept this on his desk throughout his working life. My guess is that it was a reminder of where he’d started, and how far he’d come.

If you’d like to learn more about the Willistons, I recommend Frank Conant’s biography, “God’s Stewards.” It’s in the library. Or come and talk to me. I think, since it’s a new school year, and a troubled time, we should close with Samuel Williston’s own prayer for his school, written in 1845: that it was “the earnest desire and prayer to God of the Founder . . . that his Providence, who has so signally blessed the Seminary in its foundation, may ever be as a wall of fire around it, and a light and a glory in the midst of it, and that his Spirit— the spirit of all wisdom and grace— may dwell in the hearts of Teachers and Pupils.”

Amen. Thank you. Go make history yourselves.

© Richard Teller, 2003, 2013

1After the lecture someone asked how the Willistons could have had grandchildren, given the deaths of all their children in infancy. The answer, of course, is that they adopted four children. The grandson quoted several times above is Harvard Professor of Law Samuel Williston (1861-1963); whose happy memories of childhood visits to the Homestead are recorded in his autobiography, Samuel Williston: Life and Law (Boston: Little, Brown, 1940).

Subscribe to From the Archives and never miss a post! Just use the box at the top of the page!

Best rendition of the Williston story I have ever heard.