This presentation was given at the Easthampton Congregational Church on October 11, 2014, part of the Easthampton CityArts+ monthly Art Walk. The text and graphics have been slightly modified for this blog.

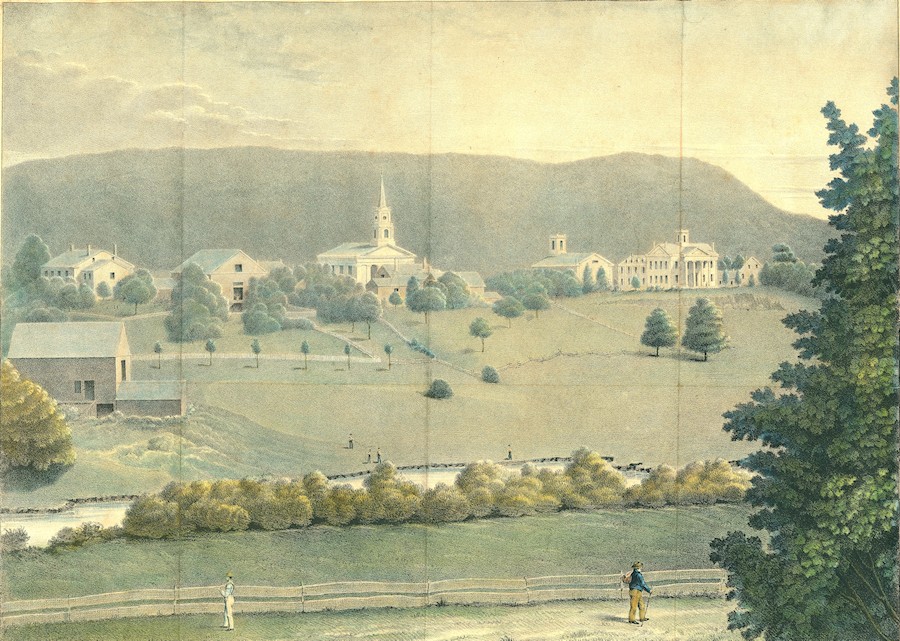

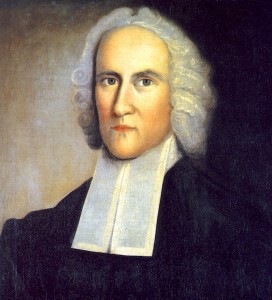

At the time of New England’s Great Awakening, when Jonathan Edwards was pastor in Northampton, Easthampton did not exist. There were a few landholders in the village of Pascommuck, out on what is now East Street. Late in life Edwards would recall that around 1730 “there began to appear a remarkable religious concern at a little village belonging to the congregation, called Pascommuck . . . at this place a number of persons seemed to be savingly wrought upon.”

Note Edwards’ phrase, “little village belonging to the congregation.” In colonial Massachusetts, church and town were interdependent. One could not exist without the other. In 1781 Easthampton residents, citing the growing size of their village, petitioned for severance from Northampton. Attending services in Northampton cannot have been convenient – it was a ride or walk of five or more miles, over roads that barely deserved the name.

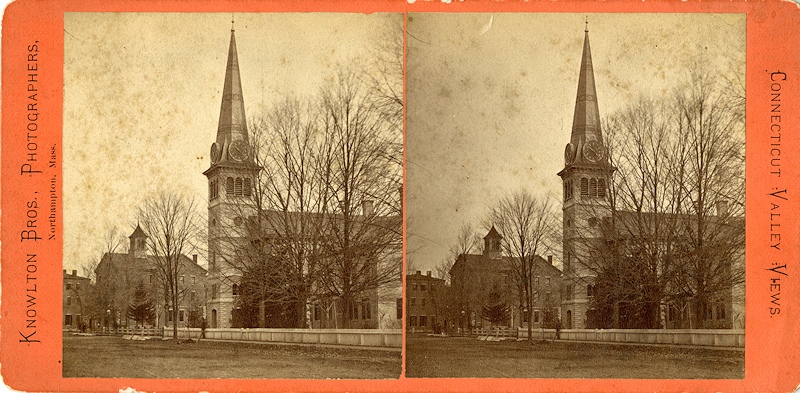

Anticipating the success of their request, they began construction of a meeting house on the town common, now the rotary. However, Southampton, only recently independent and perhaps fearing the dilution of their own small congregation, blocked the petition. It was not until June of 1785 that the Northampton church agreed to the formation of an Easthampton parish, thus allowing the town of Easthampton to be incorporated. The following November, 46 adults were dismissed from the Northampton church to form the first congregation in Easthampton. 15 Southampton families followed, and the congregation was formally organized on November 17. Continue reading