This presentation was given at the Easthampton Congregational Church on October 11, 2014, part of the Easthampton CityArts+ monthly Art Walk. The text and graphics have been slightly modified for this blog.

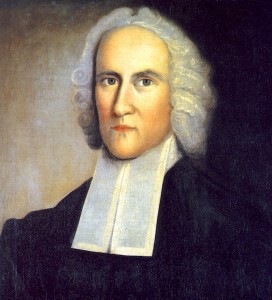

At the time of New England’s Great Awakening, when Jonathan Edwards was pastor in Northampton, Easthampton did not exist. There were a few landholders in the village of Pascommuck, out on what is now East Street. Late in life Edwards would recall that around 1730 “there began to appear a remarkable religious concern at a little village belonging to the congregation, called Pascommuck . . . at this place a number of persons seemed to be savingly wrought upon.”

Note Edwards’ phrase, “little village belonging to the congregation.” In colonial Massachusetts, church and town were interdependent. One could not exist without the other. In 1781 Easthampton residents, citing the growing size of their village, petitioned for severance from Northampton. Attending services in Northampton cannot have been convenient – it was a ride or walk of five or more miles, over roads that barely deserved the name.

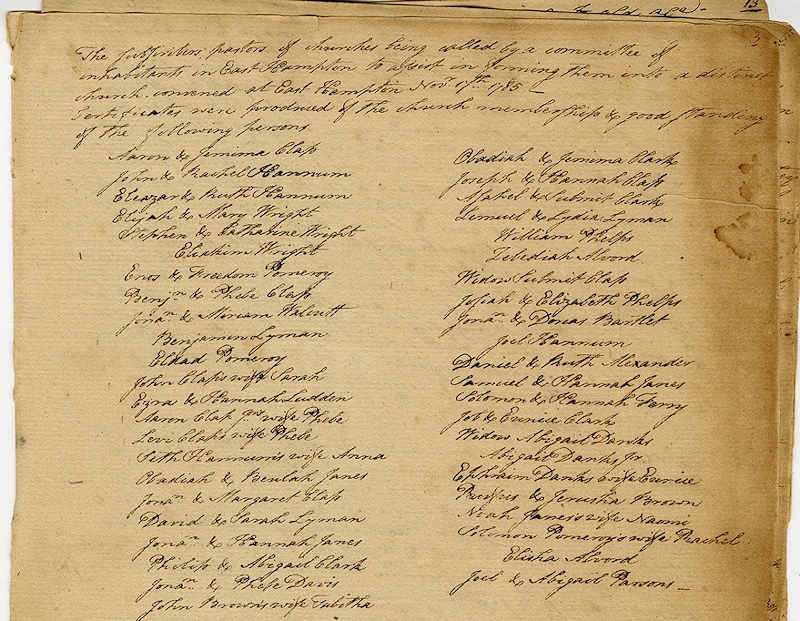

Anticipating the success of their request, they began construction of a meeting house on the town common, now the rotary. However, Southampton, only recently independent and perhaps fearing the dilution of their own small congregation, blocked the petition. It was not until June of 1785 that the Northampton church agreed to the formation of an Easthampton parish, thus allowing the town of Easthampton to be incorporated. The following November, 46 adults were dismissed from the Northampton church to form the first congregation in Easthampton. 15 Southampton families followed, and the congregation was formally organized on November 17.

You’re looking at what I consider a fairly astounding document. From the archives of this congregation, it is the minutes of the very first meeting to organize the parish. The names here are those of the first families in the village – Clapp, Janes, Hannum, Wright, and more. Many of these are common names in town today.

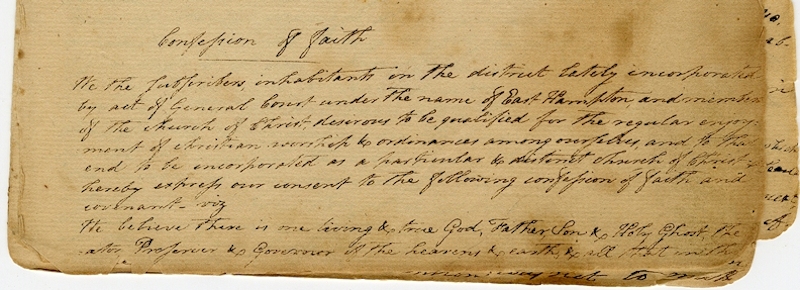

Having agreed to form a congregation, the next business was a declaration of faith. In the Congregational tradition, each parish was responsible for deciding exactly what it believed. Even in ultraorthodox 18th century Massachusetts, this was so. It remains so today.

The meeting house was duly completed. I’m going to read from a memoir from the church archives. Unfortunately we don’t know who the author was, but he mentions that he was born in Easthampton in 1856. I’m guessing that this was written for the church’s 125th anniversary in 1910.

“No one now alive ever saw [the meeting house], but this is a description told to me by two old ladies. It was a frame building facing South, with neither steeple, bell, or heat. The church service began when the minister arrived, called together by the blowing of a conch shell or the beating of a drum. The pulpit was high, reached by circular stairs and over the minister was a huge hollow sounding board, while below was the deacon’s seat. The pews were square with seats on three sides and with doors which banged and had buttons to keep them shut and the drafts out. The women brought foot stoves with coals inside, while the men wore tippets and mittens and sometimes their hats. They were rugged New Englanders. The boys sat in one gallery, the girls in another, and the choir faced the minister. A tything man was in attendance to keep the boys straight. The hour glass told the minister the time. Lengthy sermons were expected.”

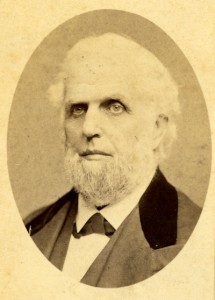

Initially the Rev. Aaron Walworth was hired to preach, then a Mr. Hold. Neither was willing to agree to remain as the permanent “settled” minister. But in 1789 Payson Williston accepted a call to the pulpit. Payson, a native of West Haven, CT, was 26 years old, a veteran of the American Revolution. He came from a large family of clergy, including not only his father, but several uncles and cousins. Almost all of them, Payson included, were products of Yale University, which had, in the decades prior to the Revolution, become an intellectual center of Congregationalism. Payson Williston may have been one of the last of the great Calvinists: fundamental in his approach to Scripture, one for whom Heaven and Hell were physical realities. His approach to worship emphasized Puritan simplicity. This would eventually bring him into conflict with members of his own family. But if there was ever a man in a position to shape the thinking of his congregation, it was Payson Williston, who served for 44 years, and lived, with all his physical and mental faculties intact, for many years after his retirement. He made it to 92, an almost legendary age in those days.

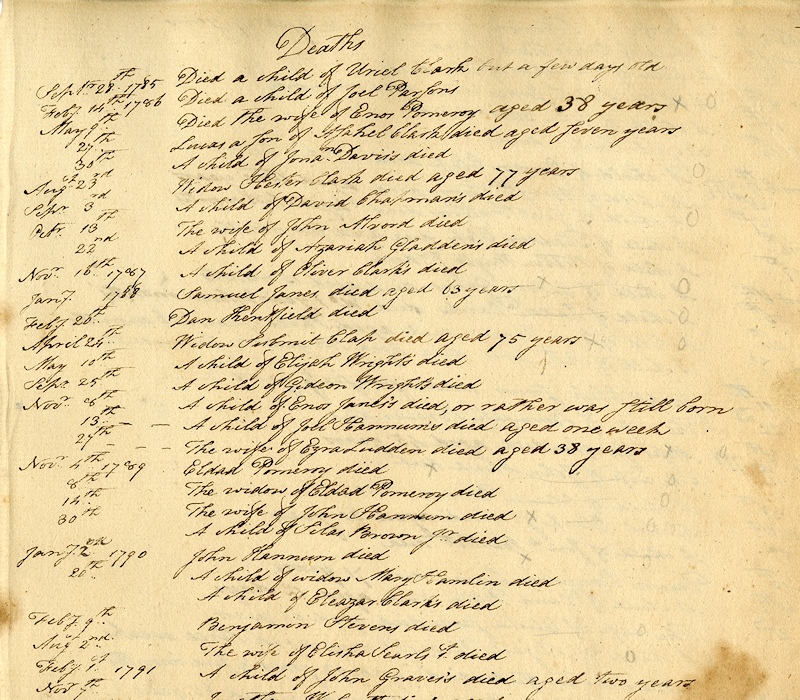

Since I live for and with old paper, I’m going to dwell on that first church register for a moment more. It really is a gold mine of Easthampton history. Fundamentally, the congregation was the town and vice-versa, so many of the early records are here. These are marriages, performed no doubt by Payson Williston himself – I think the handwriting is his.

And more sobering, here are deaths. The number of children is appalling. At a time when antibiotics were unknown, when medicine was practiced by barbers, it must have been an act of tremendous faith just to bring a child into the world. The odds were against them.

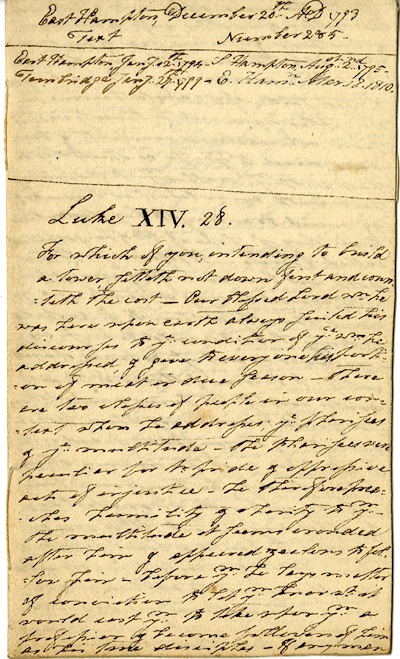

Like many in the Great Awakening, Payson was also an active evangelist. In 1805 he took leave of absence to perform missionary work in upstate New York. Late in life he would note that he was especially proud of the five revivals he had conducted in Easthampton, in the course of which dozens of individuals had publicly acknowledged Jesus as their Savior. He had a reputation as a good speaker – not the liveliest or most inspiring, to be sure, but one who spoke with clarity and sincerity. When the congregation was expected to hear sermons of an hour or more every Sunday, that was important. Among the archives of this church, the public library, and Williston Northampton, hundreds of his manuscript sermons survive. This one, according to the note at the top, was preached in 1793, repeated in Southampton in 1795, and again here in town in 1810. Judging by Payson’s tiny handwriting, his eyesight must have been extraordinary to the end of his life.

Payson was considered the most learned man in town, respected and revered long after he had retired from 44 years in the Easthampton pulpit. Rarely has it been suggested that he had a sense of humor. But in 1839, six years into that retirement, he returned to the pulpit to celebrate the 50th anniversary of his arrival in Easthampton. After speaking at length about his own and the town’s history, he turned his attention to his former flock and said, “Many sermons you have heard from men who have come to you as messengers from God; and, in the course of my long ministry, I have delivered to some of you hundreds and hundreds of them – and apparently, without any permanently good effect.”

The meeting house, which also served for meetings of secular kinds, including town government, stood on the common. The common, only a postage-stamp sized piece of which remains, actually encompassed all of upper Main St., from behind the present-day Memorial Hall to the traffic light. As the name suggests, it was “common land,” where villagers could meet, conduct business, graze livestock, etc. But Easthampton desired a “real” church. Payson Williston’s successor, William Bement, would see it built in 1836.

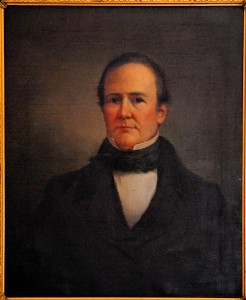

And it is here that we meet the second of the Willistons, Payson’s eldest son Samuel. This is not the place for an extended biography of Samuel Williston. Suffice to note that Samuel had intended to follow in his father’s footsteps to Yale and into the family profession of preaching. But young Sam’s education was drastically curtailed when his eyesight failed him at age 18. He set about learning the retail dry goods trade, first in New York, then back in Easthampton and Northampton. It turned out that he had a head for business.

He eventually met the third Williston in today’s narrative, Emily Graves, the daughter of the minister in Williamsburg. They were married in 1822 – and moved in with Sam’s parents. Emily, who shared Samuel’s business acumen, developed a method for making a fancy cloth-covered button. The two of them set up a cottage button manufacture ultimately involving nearly a thousand households up and down the valley. They were immediately, and spectacularly successful. Samuel invested the proceeds in other industries, notably cotton thread and elastic webbing, but also banking, railroads, and much more.

By the time Payson Williston retired in 1833, Samuel was one of the wealthiest men in New England. His success was tempered, though, by the loss of four infant children. Literally fearing that the Lord was somehow displeased, he and Emily vowed to use their material successes to do the Lord’s work, acting as, to borrow the title of Frank Conant’s excellent biography of the Willistons, “God’s Stewards.” They were tremendous contributors to educational causes, including Mount Holyoke, which they helped found, and Amherst, which Sam rescued from bankruptcy. Williston support went to missions, and local church efforts.

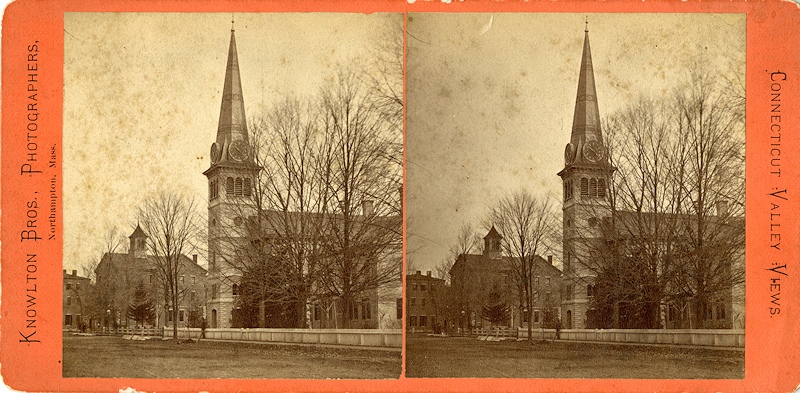

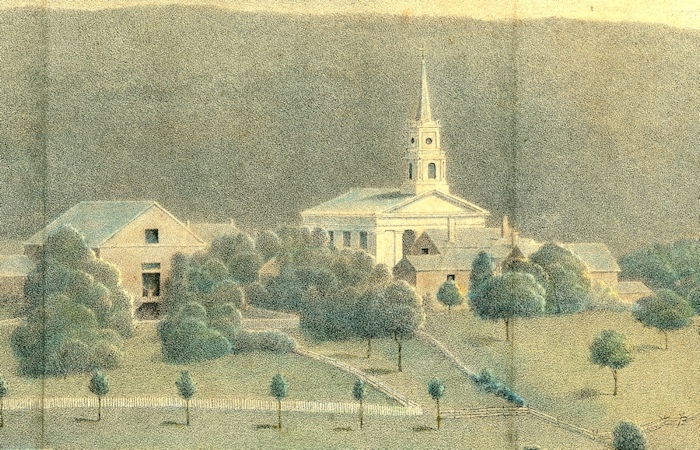

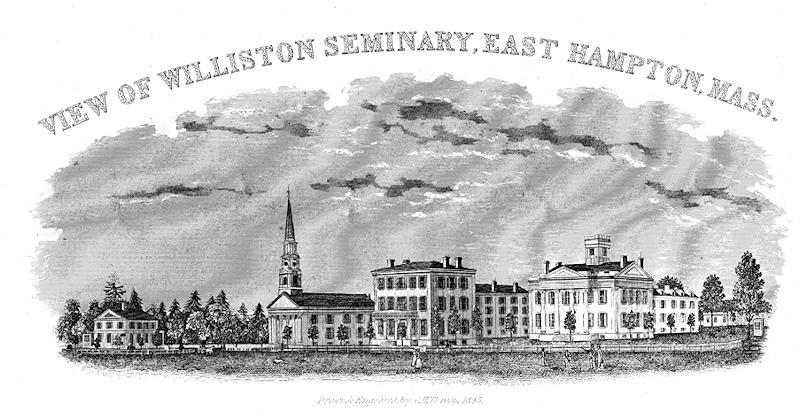

Thus, in 1836, when the time came to build a real church, Samuel Williston put up much of the money. The First Church rose on the Town Common east of the old meeting house, on a site now occupied by the Easthampton Savings Bank. (For more information concerning the preceding image, please see “The Old Neigborhood, 1844.”)

In 1841, Samuel acted on a longtime ambition and founded what was then called Williston Seminary. The first buildings were on the Common, south of the First Church. Seminary students used the Church as their house of worship, occupying the gallery pews. And, perhaps as a sign of things to come, Samuel paid to have the church picked up off its foundations and moved back 50 feet, so that the facade lined up nicely with the Seminary buildings.

Prior to 1834, by law it had been the responsibility of each town to support its Congregational Parish. But Massachusetts disestablished religion in that year (only 25 years after the First Amendment), thereby not only opening the Commonwealth to religious freedom, but requiring that churches become self-supporting. (Yes, “disestablished.” Remember back in the 6th grade, learning to spell what we all thought was the longest word in the English language? Samuel Williston was an antidisestablishmentarianist.) In most cases, including Easthampton, a Society was formed, which took responsibility for raising funds, paying the bills, and hiring the minister. Samuel Williston, since 1841 a deacon of the church, was a member of the Society, along with his business partner and protégé, Horatio Knight. Whatever their motives, there was no question where the money was coming from. Sam also funded the construction of the town hall, the first public school, founded two banks . . . and on and on. He who paid the piper expected to call the tune.

With industrialization, Easthampton was growing rapidly, and the First Church was already too small. As early as 1849, Samuel was jotting down notes about the potential dimensions of a new building. In 1851, the congregation met to discuss the possibility of a second structure. It was a controversial idea. The First Church, after all, was a mere 15 years old. Opinions differed as to whether the congregation should divide, or a new church be built that would accommodate everyone.

Gradually it became evident that no agreement was to be reached. In 1852 the Payson Church Parish, named to honor the first pastor, was formed, and construction begun on a new building. A large number of First Church families left to join the new parish, including the 3rd minister, Rollin Stone, and the principal benefactor, Samuel Williston. 90-year-old Payson Williston, despite the honor accorded him in the naming, chose to remain with his old congregation. One can imagine him sadly shaking his head and muttering, “vanity.”

For the real divisions appear to have been over doctrine and forms of worship. All kinds of -isms: transcendentalism, romanticism, and most of all, materialism had softened the Puritan outlook of the younger generations. While some, like Samuel, would retain their Calvinist views concerning obligations to the Lord and fellow man, most, including even Samuel, had little patience with the hellfire-and-cold-water discomforts of Jonathan Edwards’ day. Many of the older families in town stayed behind at the First Church, while newer and wealthier members went to the Payson Church. To his credit, the new First Church minister, Aaron Colton, worked hard to heal some very deep wounds.

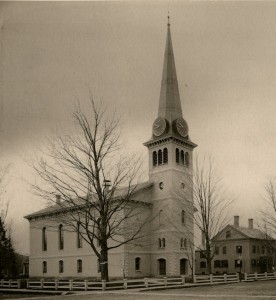

For those who believed that the Lord sent signs and portents, the first few years were a trial. The Payson Church, finished for a little more than a year, burned in January 1854. There was no insurance. Samuel Williston agreed to pay for reconstruction, which was about three-quarters complete the following August when the building burned again. Once more Sam picked up the tab. (If you’ve ever wondered why the bricks are painted white, it’s because they were reused after the fires.) The third, and present house was completed in 1855, but not before the congregation had met to pray over the question of whether or not the Lord really wanted them to proceed. Payson Williston, perhaps as a gesture toward reconciliation, donated the pulpit Bible, while Sam, whose purse was smarting from having paid for three churches to get one, became better acquainted with the newfangled insurance industry.

It was fortunate, for his trial by fire was not yet over. The Seminary building burned to the ground one afternoon in 1857. (I sometimes like to think that God’s plan for Sam Williston included attempts to keep him humble.) (See The Great Seminary Fire and Abner Austin, Fireman.)

And – you may interpret this as a final sign, or pure coincidence – in 1862, by which time one assumes the congregation was starting to feel a bit more secure, a huge gust of wind, possibly a microburst, blew the Payson Church spire over onto the roof and into the sanctuary. According to one description, the lower part of the tower crashed into the church, while the tip missed the building and impaled into the ground. The rebuilt steeple is a full 40 feet less ambitious than the original. Happily, it has stayed put for 152 years.

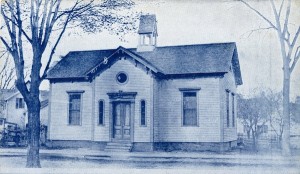

Meanwhile, Easthampton was changing. No longer just a farm village, it was becoming a manufacturing center. A new population was streaming into town to work in the mills – from Ireland, Poland, Germany, later Quebec. They needed housing, stores, banks, schools, parks – Samuel Williston and his associates, almost all of whom were prominent members of the Congregational Church, saw to it that they were built. They also needed churches. A kind of satellite worker’s chapel was provided. What was called the Union Chapel was constructed in a neighborhood of workers’ residences, near the present day Maple Street School on, yes, Chapel Street. Eventually it was purchased by a new congregation of Lutherans. Sam Williston also donated land for Easthampton’s first Catholic parish and Saint Brigid’s Cemetery. This may have come with some personal struggle, considering that he came from a background that was often openly anti-Catholic. But the needs of his workers seem to have been paramount.

The Payson Church prospered. It supplanted the First Church as the designated house of worship for Williston Seminary students. This was not always a happy arrangement. Despite the “Seminary” name, Williston was a nondenominational school, accepting students of all faiths, but requiring an enforced Protestantism that was sometimes actively resisted. This could manifest itself in strange ways. Before reconstruction of the sanctuary in 1862 the organ and choir were in the rear gallery, and there was occasional confusion among the congregation whether people should turn and face the rear during hymns. On one occasion Seminary students, occupying the side galleries, turned and sang facing the wall. The formal association appears to have lasted until the 1920s. It had been customary for Williston students to attend as a group, led by the headmaster. But during Communion services those students who wished to were allowed to leave. One Sunday the Rev. John Findlay rebuked the departing boys from the pulpit, insisting that they remain. They did, but that was the last time that students were required to attend.

The rest of my narrative is brief. In 1866 Samuel, exercising his occasional tendency toward behaving like the Emperor of Easthampton, moved the First Church a second time, to its final site at the end of the Common, left of the new High School, now called Memorial Hall, so that he could build a new building at the Seminary. Short of funds, and still reeling from the schism, there was probably little the old parish could do about it. Through the rest of the 19th century the Payson Congregation prospered, while the First Church’s numbers dwindled. Efforts at conservation during World War I led to joint services between the two congregations, which laid the groundwork for reconciliation and reunification in 1918. The emergence of the unified Easthampton Congregational Church in that year brought an end to the First Church’s life as a house of worship. It was used for a few years as an entertainment and movie hall before succumbing, mercifully, to fire in 1929. As for the present church, the last century has seen great changes and strides forward, about which others present are far more competent than I to speak.

Here are few looks at how the interior has changed. Keep in mind that prior to 1862, the organ was in the rear gallery. There are no pictures. During reconstruction following the collapse of the tower, it was moved to the front, where it remains today.

Music was always an important tradition in this building. Samuel Williston donated pipe organs to both churches. There has always been a strong choral music tradition – in fact, in the 19th and early 20th centuries the church employed two organists and choir directors, George Kingsley and Frederick Clark, who had national reputations as composers and compilers of hymnals. And many here today fondly recall the legendary Natalie Strong, who introduced hundreds of children to choral singing and played the organ with special panache — and in her stocking feet. Her own family roots went back to the early days of this town and parish.

We should also mention the role that the women of the church took in the community and the world. There were a number of especially strong women – besides Emily Williston, Lucretia Ferry and Sarah Elizabeth Chapin were genuine leaders in the town. They founded several missionary and service organizations, including the Helping Hand Society, which remains active to this day. Sarah Chapin was hired by Sam Williston to run the ladies’ department at the Seminary, then became Principal of the new public High School when it opened in 1864, and went on to a long and distinguished career in the Easthampton Schools.

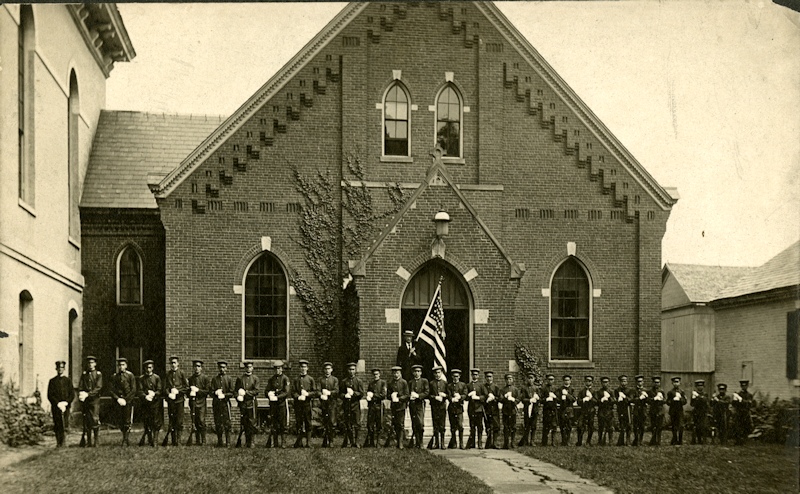

The Fellowship Hall, shown below on July 4, 1910 with the Congregational Church Cadets, was a gift of Emily Graves Williston, who was a philanthropist in her own right. Besides the Hall, she donated a Communion service which I understand is still in use, was a major donor to Mount Holyoke College, and was active in many missions and church activities. In 1881 she built the Easthampton Public Library, which had been founded by Payson Williston and which today bears her name.

More to the point, Emily Graves Williston was – I quote her grandson, also named Samuel Williston – “the embodiment of gracious dignity . . . a wise woman . . . and not afraid to smile.” She appears to have been the humanizing factor in a family dominated by Payson and Samuel, two of the most stubborn, stiff-necked old Yankees imaginable. Toward the end of her life, Emily left these words with the Reverend James Morris Whiton, and I will leave them with you: “I thank God for the opportunity to do my part in a time of colossal change.”

I grew up in the Easthampton Congregational Church in the 1940’s,50’s & 60’s. Although I left Easthampton in 1984 there is still a special place in my heart for the town and ECC. Thank you for sharing your knowledge and the research you’ve obviously done. I worked for and was very close to the Strong’s and was one of the children you referred to that sang in Natalie’s choir. Sorry I wasn’t able to come up to hear your talk in person – I remember your folks well.

Forgive me for being a bit glib about a fascinating and informative article, Rick, but one of my takeaways from this is how remarkable and cool it was that the First Church’s 3rd minister was named “Rollin Stone!” Far out!

Neat history, RT. The “Congo-Bongo” remains seared into my childhood memories from the ’40’s through ’60’s, and it would take a three year stint as a Congregational missionary to Turkey from 1966-69 for me to become a devoted apostate ;-). The edifice itself is such a welcome to Easthampton that it’s sad the clock is in disrepair, despite the town’s kicking in over the years for its upkeep. The Tannatts, pere and fils, who could and can, respectively, fix anything, did their best to keep it going with baling wire and chewing gum in the absence of spare parts . Would that someone with deeper pockets than I could spring for a replacement, perhaps with a streaming, digital stock ticker banner underneath to honor Sammy my Sammy.

Thanks, John. I’ve just returned from a delightful and rich experience at our, now combined, alma mater. Sounds cool, eh?

Your piece adds genuine Easthampton historical substance, from a ‘kid’ who had only to roll out of bed and stumble across the street to attend a splendid academic college prep school.

Reading your response to RTeller’s presentation, sent me back to reread his amazing account. When I attended ‘Hamp’ for 10th -12th, graduating in ’63, I know that I felt there was something very special about it and the two Misses. I knew that character, community and purposeful learning were key, and that deep love of learning accompanied the steady, disciplined energy they maintained even in 1960-63.

I absorbed more than I knew, until now. As I began Rick’s recognition of the 40th combined year, I thought I’d pick up a bit of info I hadn’t sought or heard; I didn’t expect the gift he gave, the richness that became part of who I am.

So, John, the times we shared ‘there’, in music and theater and at events between campuses, were actually the part you and I played in the beginnings of drawing the two schools together; from 62-63, each year increased the sharing and blending. it wasn’t long before situations presented the necessities that ‘crash-banged’ the two together. Too bad it was so painful for those who weren’t ready.

I am filled with gratitude that the work has, and is, being done to assure that WNS continues to thrive.