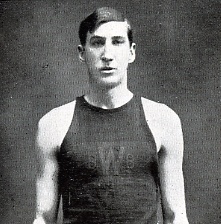

This is presented as an addendum to Doug Stark’s article on the History of Williston Basketball. Without question, our first “great” player was Joe Lynch, class of 1910, who was inducted into the Williston Northampton Athletic Hall of Fame on June 7, 2014. These remarks were delivered at that event.

I’m here to present Joseph Lynch, Williston Seminary class of 1910, for the Athletic Hall of Fame. Joe was an Irish kid from Holyoke, who attended Holyoke High School before enrolling in the Middle Class — what we would now call the 10th grade — at Williston. Other than that, we don’t know much about him. I’d like to say that he presented the prep school ideal of the scholar-athlete, but I’m afraid that his grades don’t bear that out. The archives actually have a paper that he wrote, about the financier Edward Harriman, that is reasonably literate and shows some insight. Other than that, there’s not much. His 1910 classmates elected him “Best Athlete,” as well as “Merriest,” “Biggest Rough-Houser,” and “Biggest Bluffer.” His yearbook notes that he was “a lover of nature,” and a member of the F. C. Fraternity, about which we know little, and something called the Vigilance Committee, about which our ignorance is probably a blessing.

Joseph Lynch excelled in sports. He played right guard on an intramural football team, but he was in his element in baseball and basketball. Joe was the first baseman on the Williston Nine for three reasonably successful years — although interestingly, Holy Cross turned him into a pitcher. And there is a suggestion that he struck out more often than his friends and teammates might have liked.

But in basketball, Joe Lynch was unstoppable. Standing six-foot-one, towering over his teammates in an era when kids were simply shorter than today, he was an ideal center. His long arms and quick feet made him a defensive monster. And he was a scoring machine. Over his career, he scored 394 points in 28 games. Before you exclaim, “but that’s nothing!”, remember that the game of basketball, invented only 17 years before Lynch arrived at Williston, was very different. Dribbling, for example, was rare; players moved the ball primarily by passing. Players thus tended to spread out more, playing what we would now call zones. Most shots came from a distance, so scores were lower — and of course, the three-point shot hadn’t even been dreamt of. Foul shots were rare, and the free-throw line was 20 feet from the basket. Even the metal hoop and net, which replaced a bottomless peach basket, had been introduced only as recently as 1906. Continue reading