Williston Northampton is 175 years old this year. But almost forgotten amidst the dodransbicentennial [yes, it’s a real word!] hoopla is another milestone: Ford Hall opened a century ago this fall.

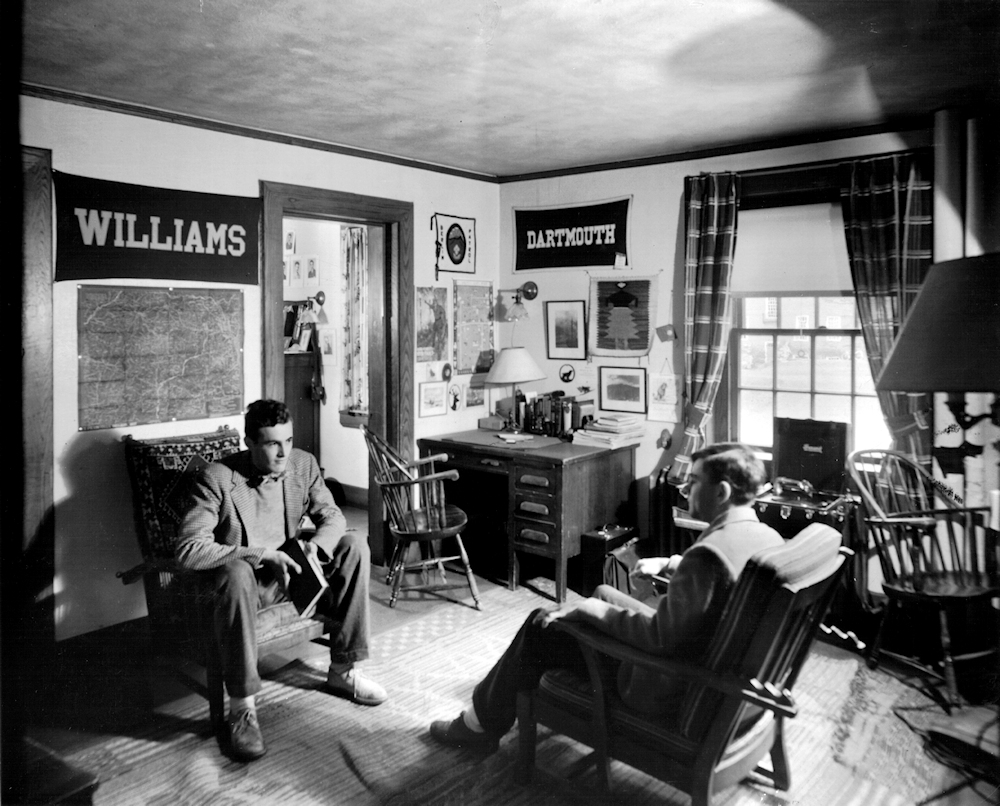

After the Homestead, it is the first structure to have been built on the so-called “new” campus. The Senior Dorm. (Not any more.) The Gold Coast. (No longer.) The Fraternity. (Ditto — perhaps, perhaps not.) Even in these unsentimental twenty-teens, some students — many of them the sons of alumni — will claim that to live in Ford Hall is to have arrived. It goes without saying that their non-Ford peers might not agree.

But if any campus building can be said to embody Tradition, with a capital T, it must be Ford. No doubt some individual traditions are best left unrecorded in a family publication like the From the Archives. Alumni of various generations will recognize references to the Phantom, those “useless” fireplaces, the Bomb Sight, the Great Newspaper Caper, Couchie’s Carlings, and the mythical Kid Who Was Taught His Colors Wrong. If you have to ask, you weren’t there.

On the other hand, readers who were there are invited to add their favorite Ford Hall stories to the comment form at the bottom of this article. What, after all, is a history blog for? Be advised, though, that publication is likely, unless you’ve forgotten that there is no statute of limitations on good taste.

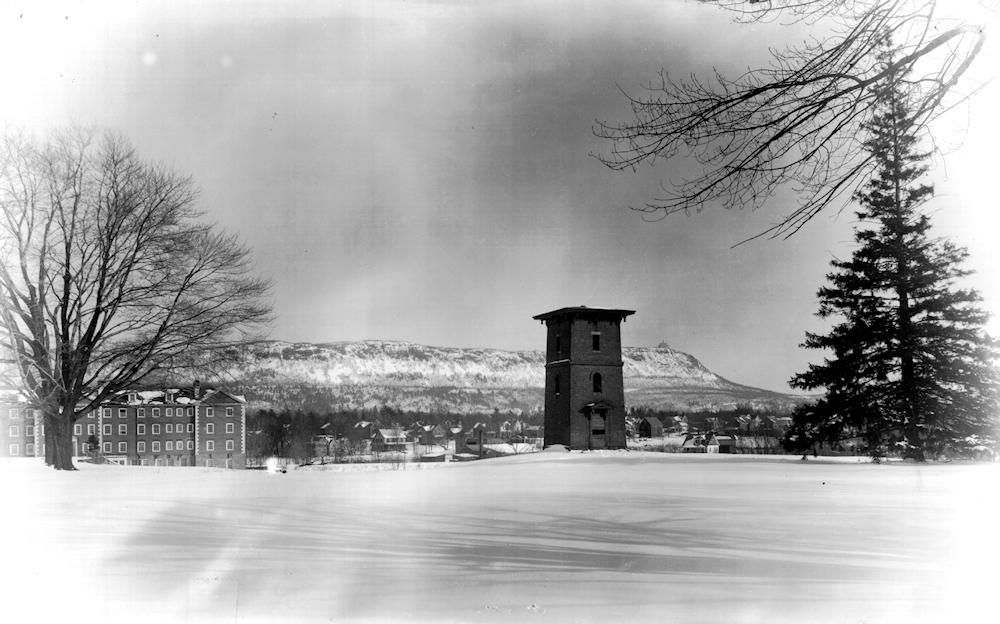

It is hard to imagine that a structure so much a part of the fabric of Williston Northampton life was almost never built. Samuel and Emily Williston’s estates had provided an endowment for the operation of the school, which was originally situated at the head of Main Street, on a site now occupied by two banks and a supermarket. Emily’s will conveyed the Homestead and surrounding land — the present campus — to Williston Seminary, with the proviso that the school erect at least one new building on the property.

That was in 1885. A quarter-century later, nothing had been built. Much of Samuel Williston’s endowment comprised securities which had not yet matured, and factories which had, as New England’s textile industry moved south, become unproductive. The Seminary’s debt was substantial. In 1899 Headmaster Joseph Sawyer turned to the school’s alumni for assistance. He sought $25,000. As Sawyer wrote in his History of Williston Seminary (1917), “the effort failed through the inexperience of the solicitor, and . . . because it was the first time aid had been sought for the school through gifts from friends, and in consequence the belief prevailed that the school had superfluous wealth.”

But Sawyer, nothing if not persistent, kept asking, and financial support began to arrive. He and his trustees instituted a variety of economies which, if not rectifying the school’s finances, at least stabilized them. Sawyer had the vision to realize that for Williston Seminary to succeed in the new century, a commitment must be made to progress. Modernization of the curriculum and expansion of athletic and extracurricular programs were part of this vision. But a physical commitment to the future was essential: Sawyer desired a new, modern dormitory on the Homestead property, which would stand in contrast to the aging structures on Main Street. It would be the first step toward an eventual move of all school operations to the present campus.

Such a building program, initiated just as the world was sliding irrevocably into the First World War, was risky. The War, and a weak national economy, were causing a substantial decline in enrollment, and the school’s deficits were mounting. Arguably, any project requiring cash should have been put on hold. But a donor, John Howard Ford, class of 1873, came forward.

In a bizarre combination of circumstances, John Howard Ford never knew he’d built the building. For many years Ford had maintained no contact with the school. By 1910, Williston no longer had even an address for him. Nonetheless, in 1914 two alumni, James Sheffield ‘82 and Charles Hill ‘90, called on Ford. They appear to have been acting independently of the school administration. But they knew of Williston’s need, and thought that Ford, a successful manufacturer of waterproof rubber shoes, might be convinced to be generous.

He was. Ford promised to contribute $100,000 — a huge sum for the time — toward the construction of the new dormitory, and made a memorandum in his account book to the effect that the funds should be transferred to Williston Seminary. For some reason, Sheffield and Hill never communicated this to the school. And a short time later Ford walked home in a heavy snowstorm, took ill, and died. His brother and executor, James Bishop Ford, found the memorandum and sent the money to Headmaster Sawyer. James Ford must have assumed — incorrectly — that Williston knew of John’s passing. But it was not until 1925, nine years after the building that bears his name was opened, that the administration would learn that John Ford had died in 1914.

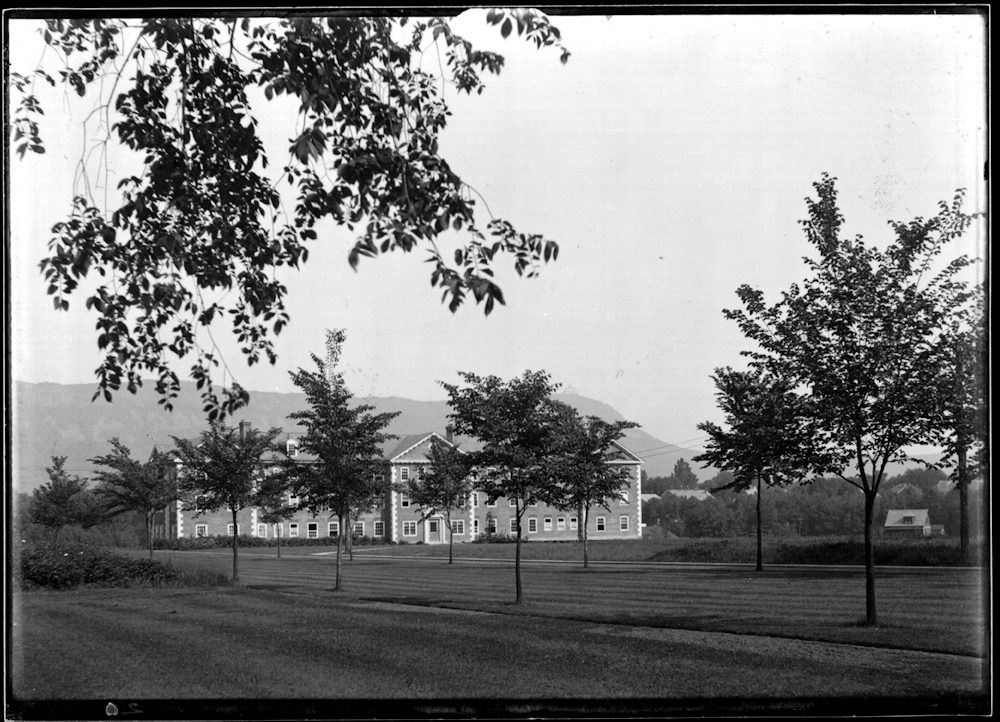

Ground was broken in October of 1915. Sawyer wrote to the alumni, “This building will establish a high standard for others that will follow. It will have reinforced concrete foundation, walls of red brick with granite corners and cornice and slate roof. The interior construction will use as little combustible material as is possible, thus making the building fireproof.” (Such foresight would prevent a disaster shortly before school opened in 1975, when an intruder left a lighted cigarette in a couch in the lobby of the dining commons.) Iron girders, concrete floors, the most modern electrical wiring and plumbing — truly, it was a model structure.

When it opened a year later, Ford would house three faculty members and fifty students in a combination of single rooms and two-person suites. Provision had not yet been made for married faculty, nor would there be for another 35 years. In 1952 the author of this article was, in fact, the first faculty child to take residence in the building. Ford Hall had its own dining hall and infirmary. Such luxuries came with a price; prior to 1950, room and board in Ford cost a student more than the more Spartan accommodations downtown.

When the downtown campus was closed in 1950, the Ford dining facilities were expanded to serve the whole school. There were several renovations and additions over the years. 1997 saw the total reconstruction of the kitchen and award-winning redesign of the dining commons, including the remounting of the Parthenon Frieze reproduction that graced the original dining room.

The consolidation brought another change. Ford was no longer “The Gold Coast.” She was reinvented as the senior dorm, with all that implied. New, shiny, but utterly unromantic Memorial Hall was designated for Upper Middlers and some Middlers (i.e., grades 11 and 10), thus creating a rivalry largely expressed via Ford-Mem water-fights that resembled Napoleonic battles. Inevitably, Ford became a seat of self-bestowed senior privilege, accompanied by certain traditions better left to the rumor mills of pseudo-history. That all ended precipitously in 1999, when Headmaster Dennis Grubbs, having observed that having all the girls’ dorms on the periphery of the campus sent the wrong message, moved girls into Mem and opened Ford to boys grades 10-12. Despite a level of fratboy anguish, lightning did not strike, nor did the earth open up. Whether such integration served to diminish the senior crime wave, or merely spread it to the lower orders, remains an open question.

In the summer of 1999, Ford Hall underwent a complete renovation, completing a cycle of improvements to every campus dormitory during that decade. There were new interior walls, windows and electrical wiring throughout the building. Faculty apartments were relocated and expanded, the common rooms refurbished, and a new common room created on the third floor. The entire building was repainted and carpeted. Yes, the windowless corridors remain sunless, and the front entrance is disproportionately small, but at 100 years, Ford wears her age well.

And now, because you’ve read this far, here’s a link to The Second-Best Ford Hall Prank Ever!