[Note: This post is an expansion of an article published in the Williston Bulletin in 2000. A few of the quoted documents have appeared elsewhere in this blog.]

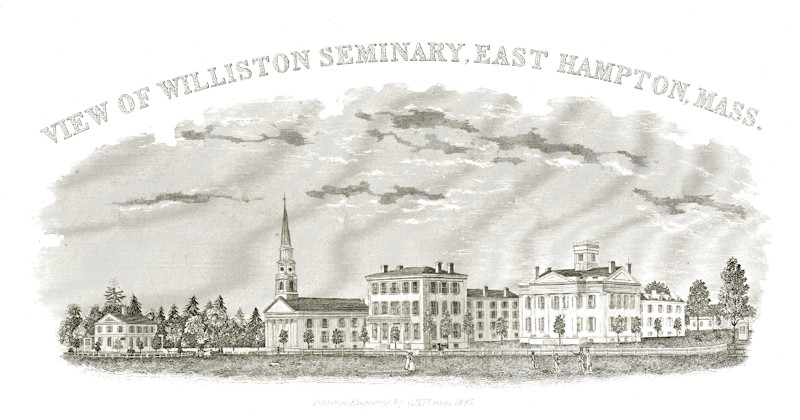

Anyone pursuing the history of Williston Seminary’s first four decades might assume that the task involves the study of dry, formal documents, the records of austere men shaping the serious minds of New England’s youth under the benevolent gaze of a saintly founder. Fortunately, we have an antidote. At a time when telephones and email were not even a dream, students wrote long, lively, personal letters, dozens of which are preserved in the Williston Northampton Archives. Most we have in manuscript; a few are copies or transcriptions of documents in private hands.

While much was happening in the 19th century world, most students’ letters barely acknowledge events away from school and home. Their concerns were necessarily more local: classes, friends, money. These letters let them speak with their own voices, and provide a fascinating window into their daily lives.

Their writing was hardly that of finished scholars. Samuel Williston once admonished that “Bad orthography, bad penmanship, or bad grammar— bad habits in any of the rudiments— if they be not corrected in the preparatory school, will probably be carried through College and not unlikely extend themselves to other studies and pursuits.” Perhaps to prove his point, we have mostly left the writers’ syntax alone, making only minimal corrections. Indeed, as student Abner Austin wrote his family in 1856, in a sentence spectacularly devoid of any punctuation whatsoever, “Mr. Williston is not the teacher he has nothing to do with it no more than you have he is the founder of it therefore it is called the Williston Seminary.”

By mid-century many New England towns were connected by rail, but in 1854 the line had not yet reached Easthampton. That April, Charles Carpenter wrote his father,

I arrived safely at No. H. on Tuesday morning. On the way, met (in the cars) with a young fellow, like myself, Williston-bound. Had to wait in No. H. all day — crowds of students came up in the train — and several stages and teams were in readiness to convey them over. Ten of us got into a three seated wagon. It was most terrific going — mud and melted snow formed a horrible coalition — Could hardly get out of a walk, a single step. We suffered the greatest trouble, however, in fear that other students would get ahead of us and engage the rooms; but after two hours we arrived — “put” for the “Sem.” The Chief Boss of the Institution, Mr. Marsh, is absent, on account of dangerous family sickness — and everything went hurly-burly. Continue reading