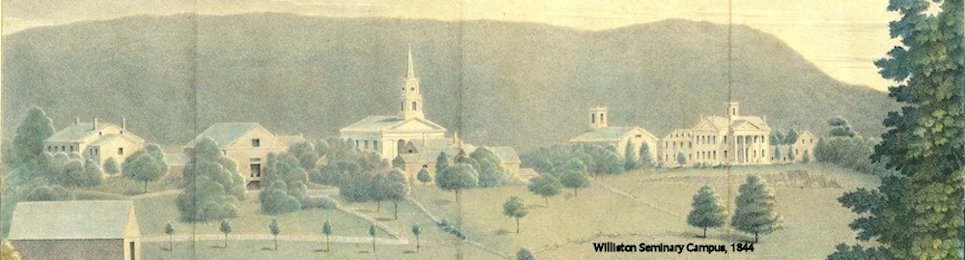

[Note: This post is an expansion of an article published in the Williston Bulletin in 2000. A few of the quoted documents have appeared elsewhere in this blog.]

Anyone pursuing the history of Williston Seminary’s first four decades might assume that the task involves the study of dry, formal documents, the records of austere men shaping the serious minds of New England’s youth under the benevolent gaze of a saintly founder. Fortunately, we have an antidote. At a time when telephones and email were not even a dream, students wrote long, lively, personal letters, dozens of which are preserved in the Williston Northampton Archives. Most we have in manuscript; a few are copies or transcriptions of documents in private hands.

While much was happening in the 19th century world, most students’ letters barely acknowledge events away from school and home. Their concerns were necessarily more local: classes, friends, money. These letters let them speak with their own voices, and provide a fascinating window into their daily lives.

Their writing was hardly that of finished scholars. Samuel Williston once admonished that “Bad orthography, bad penmanship, or bad grammar— bad habits in any of the rudiments— if they be not corrected in the preparatory school, will probably be carried through College and not unlikely extend themselves to other studies and pursuits.” Perhaps to prove his point, we have mostly left the writers’ syntax alone, making only minimal corrections. Indeed, as student Abner Austin wrote his family in 1856, in a sentence spectacularly devoid of any punctuation whatsoever, “Mr. Williston is not the teacher he has nothing to do with it no more than you have he is the founder of it therefore it is called the Williston Seminary.”

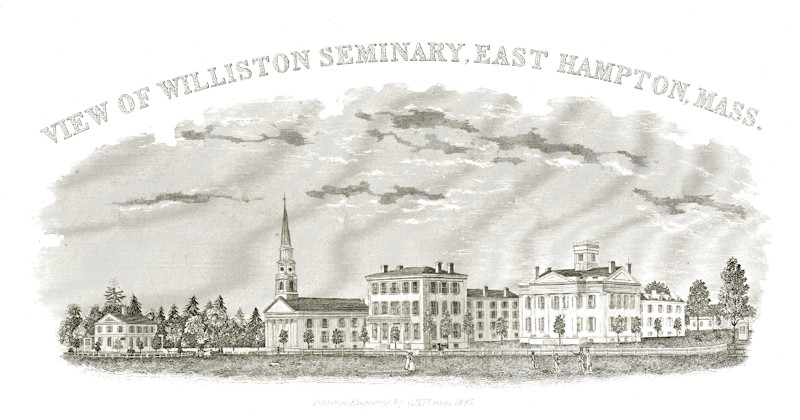

By mid-century many New England towns were connected by rail, but in 1854 the line had not yet reached Easthampton. That April, Charles Carpenter wrote his father,

I arrived safely at No. H. on Tuesday morning. On the way, met (in the cars) with a young fellow, like myself, Williston-bound. Had to wait in No. H. all day — crowds of students came up in the train — and several stages and teams were in readiness to convey them over. Ten of us got into a three seated wagon. It was most terrific going — mud and melted snow formed a horrible coalition — Could hardly get out of a walk, a single step. We suffered the greatest trouble, however, in fear that other students would get ahead of us and engage the rooms; but after two hours we arrived — “put” for the “Sem.” The Chief Boss of the Institution, Mr. Marsh, is absent, on account of dangerous family sickness — and everything went hurly-burly.

Carpenter took lodging in the “Brick Seminary,” which later generations of students would know as Middle Hall. [For full text, see “The Faculty Don’t Furnish Towels.”]

The rooms are small — have one window — one bed and bedding — a table — a desk-like shelf, for books and writing, and a small stove. There is a closet in the room, with hooks for clothes; a washstand and a bowl, pitcher and two pails; a looking glass and a woodbox, I believe complete the list of furniture supplied by the Institution. Have to pay about 2.75 each for the use of the room. We board at the Boarding House for $1.67 per week — then there are fuel, lights, etc. — Leavitt brought a lamp, which will be enough for us both. — I forgot my boot-brush — As I shall need that, I think you had better send it — As the “Faculty” don’t furnish towels, wish you would put in a couple — coarsest you can get if you please; or pretty coarse. — Slip in some matches, if you please, and the silk that Mother cut out for a pen-wiper and which I forgot. They ask enormously for everything here — 12½ for a box of 5 ct. matches — and at that rate — If there are a few of those carpet tacks left, put in a few — not particular. Our wood is greener than the imaginary dress of the milkmaid in the spelling book, and we have to use a good deal of paper.

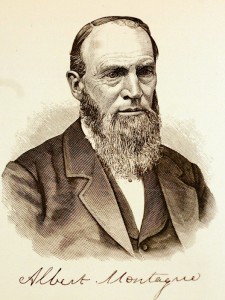

Only about half the students lived on campus. Others lived with local families, often chopping wood or tending livestock in exchange for lodging and meals, or took rooms in boarding-houses. Albert Montague, whose 1842 letters are the Archives’ earliest student documents, was one of the latter. In September of that year he described his day to his sister, Phila, in Sunderland, Mass.:

There is 20 in the club [i.e., the boarding house] of which 2 of them are teachers viz. Mr. Storrs & Mr. Clapp. We do not live quite as well as I did at Amherst but it does very well to study upon.

Arose this morning about 20 minutes before the bell rang. The bell rings at 5 for the students to get up. Study until breakfast time which is 20 minutes before 7. Had griddle cakes with molasses to put on them. At 1/4 before nine went into prayers. After prayers came into my room and studied until noon. At noon or about 25 minutes past 12 went to dinner. The rest of them had fish which smelt as strong as the fish cellars in Boston. I made out with wheat bread and butter. Recited almost all the afternoon. The bell rang for supper about 6. Had warm wheat bread and well salted butter (but no molasses) and apple pie. In the evening had the headache so that it troubled me a little. About 9 1/4 o’clock commenced writing and at 1/4 after ten am about ready to get into bed.

Montague continued,

I like it here very much and wish my father was of such means so that I could stay 3 years which is the time required to fit one for college, I believe. There are 10 lessons recited in the forenoon each day and about the same number or perhaps a little less in the afternoon. 3 of my lessons I recite to Mr. Kimball the best teacher I ever saw. He is always good natured, mild, pleasant and sociable and in fact he has numberless good traits about him and one in particular which shows a very sound mind, viz. he has just got married. There are about 130 scholars connected with the Seminary and nearly 40 of them are handsome misses. In my grammar class there are nearly 40, chemistry class nearly 25, Astronomy class about 15 and geometry class 7.

A few weeks later, Montague returned to the subject of food:

We have our food provided for us at the boarding house as usual but of all the butter that was ever made I think this must be the poorest. The next day after we got down here we had some butter of which I eat one mouthful at a meal which was quite sufficient for me. Such frowzy butter as that you never tasted of and I hope you never may, for I verily believe it was some that Noah’s wife put up and had left over after the Ark rested on Mount Ararat. We had it on the table 3 or 4 meals and all began to grow uneasy and Kingsley made a motion that we use it for boot grease.

[The complete texts of Montague’s three letters may be found at “Not Homesick in the Least.”]

Montague mentioned the presence of young ladies at the Seminary. Samuel Williston had envisioned an all-male institution, but for reasons of practicality we were coeducational until 1864 . It was generally believed that a coed environment provided too many distractions. There may have been some truth to this, if one considers the example of Lucien Tudor Platt, who wrote a friend in September, 1863, “Have got a loud old boarding place, and Ah! Ye Gods! and spirits of just men made Perfect! What a charming young damsel of seventeen summers boards with me. She is from Boston, has a face and form that a Venus might covet.”

It cut both ways. In 1845 Urania Stoughton who, with her sister Emily, lodged with an Easthampton family, told her father,

I wrote so much with Fred standing at our door trying to make Emily come out into the hall — he brought her his coat to mend and I told him the last time he was here he shouldn’t come to our room any more — if he came to see E- again, they should sit on the stairs — She told him he should come in, I told him he shouldn’t, & he declared he wouldn’t unless I went out and told him I must write a letter — said he had something to tell E- that he shouldn’t tell me at any rate and she refusing to go into the space — I told him finally I would go down for a cent — so he gave me a cent and I ran down here. Miss Brackett talks so much to us about associating with the young men, that tho’ we know there is, in reality, no harm in Calvin’s or Fred’s coming to our room yet it might make a great stir if it happened to be known — & I can’t bear the thought.

Despite its name, Williston Seminary was not a church-affiliated school. However, students were expected to participate in, if not necessarily embrace, Samuel Williston’s evangelical Congregationalism. Some responded better than others. In 1856 Abner Austin wrote,

This is one of the most Christian like schools I ever knew. They have prayer meetings once or twice a week which we have to attend. We are very pious when in sight of any of the teachers but as soon as we get out of sight of them we raise the very Devil.

Others were more serious. In 1850, Henry Nason wrote a friend,

The meetings in the seminary are very well attended. I think there is more than ordinary interest — the number of pious students is rather small — but I hope there may be an interesting time this winter. That would make things go on more pleasant — and what greater blessing could we ask — it seems a long time since there was very much interest, and it seems to me that if those who profess religion would do their duty as they ought, there would be a different state of things.

In 1867 Frank Davol told his father that “The report is around that Dr. Seelye is going to leave his church next year. Lately he preaches only twenty or twenty-five minutes. Of course, it suits the students, but not the town folks.” But a year later, in January, 1868, he would write,

You will be a little surprised when I tell you I think I have found my Savior . . . Dear father, with your prayers at home I will be a better boy . . . Since I have changed my life I want to see Mother very much. I want to talk, I cannot write her all the things that are in my mind.

Davol had an enthusiasm for politics, as well. The following September, he wrote his father,

We are overflowing with patriotism up here at school. We have formed a Grant & Colfax club and have bought a very handsome banner.

Students led busy lives away from study and prayers. When limited opportunities for social contact forced boys and girls to be creative, activities such as weekend plant-collecting expeditions became important recreational events. Urania Stoughton wrote, “There was a botanizing excursion last week — Two gentlemen of the class wanted to go with E- but Mr. Russell Wright took her away with himself and Miss Stacy.” [See “Botanizing”.] Other activities included attending lectures — Albert Montague mentions hearing Abolitionist speakers several times — and debating, interest in which surged in the 1850’s and 60’s.

Whenever possible, students sought outdoor entertainment. Arvine Wales wrote his mother in 1887, “My bicycle is not worn out, but I have stretched out so, that the cranks are short for me. And as I don’t get livery horses, I would like to see the country around here on my wheel.” Mount Tom was a popular destination for hiking and picnics. In the winter, wrote Abner Austin in 1856, “There is a huge pond close by and we have great times skating. . . . I have had one good sleigh-ride to North Hampton and back which cost 50 cts. apiece. It is glorious sleighing up here I tell you.” Sleighing appears to have been immensely popular. It was also the only reliable means of transportation on snowy roads. James Flower and two friends sleighed home to Ashfield, about 20 miles from Easthampton, for Christmas in 1867:

We went to the stable and engaged a team. The sleighing was splendid for the first ten or twelve miles, but after that the road was not trodden very much and consequently the sleighing was not so good. But when we had nearly reached home we found the sleighing better if anything than it was at first. When we were passing through Haydenville, the fellow who was driving, not being accustomed to the road and wishing to show of his superior horsemanship by running by a team, got into the wrong road and went around a meeting house, and when he got back into the road again he started back for East Hampton. Pretty soon we convinced him that he was on the wrong road, then he turned around and started right again.

After this nothing of any interest happened until we had nearly reached home, when going up a hill as one of the boys sat near the edge of the seat we gave him a push & out he went, rolling in the snow. We started the horse up & ran away from him, after we had gone a little way we thought we would have compassion on him, so we stopped & let him get in.

But horseplay could get out of hand. One warm night in May 1862, Frank Moore wrote a friend,

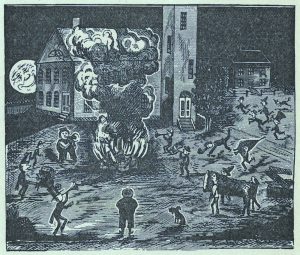

We are going out tonight to have some fun, build a great bonfire and then get out the [fire] engine. . . . While I was writing the last sentence I was interrupted by 2 boys under my window ready to go to the appointed rendezvous. . . . They were all there, 30 or 40 in number, and all in such perfect disguise that I did not know my most intimate friends. The place for the fire was some distance from the Sem. and the engine house is in the immediate vicinity of the Sem. We collected barrels, boxes, rails, etc. in an enormous pile and when ready started the engine. We dragged the engine nearly there and then some of the boys who had been at the pile at a signal, lighted it and away she blazed. Grandly and defiantly the flames arose and soon the hose was on, the suction down and out squirted the water. We were however very careful not to put much water on the fire. Scarcely had we begun to work when the factory bell began to ring as the watchman had been attracted by the flames. Instantly we took to our heels, scattering around, each for himself. As I was running I heard a voice crying out. “You’re a d–d pretty set of boys” accompanied with a rawhide around some unfortunate’s legs. I have found out during the day that at least seven boys were caught and have been suspended from school for the present. The town people are terribly enraged and intend to have the boys who have been caught arrested and an action taken against them for damage. I have not been implicated yet but I fear I shall be every minute. In case I am I shall be expelled perhaps and likely engaged in a law-suit. This seems pretty serious especially as I was the one who proposed it.

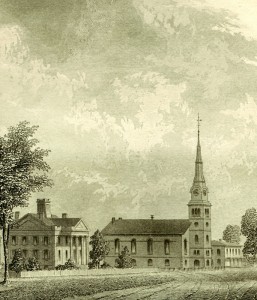

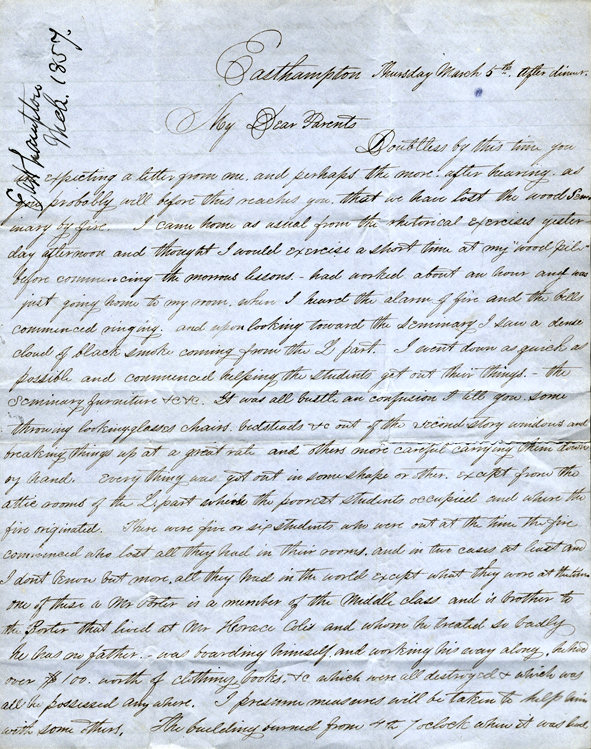

School and town were justifiably sensitive about recreational pyromania. Disaster had struck the school only five years earlier. On March 4th, 1857, Henry Perry was cutting wood for his host family

. . . when I heard the alarm of fire and the bells commenced ringing. And upon looking toward the Seminary I saw a dense cloud of black smoke coming from the L part. I went down as quick as possible and commenced helping the students get out their things — the seminary furniture, &c &c. It was all bustle and confusion, I tell you. Some throwing looking-glasses, chairs, bedsteads, &c out of the second story windows and breaking things up at a great rate and others more careful carrying them down by hand. Everything was got out in some shape or other, except from the attic rooms of the L part which the poorest students occupied and where the fire originated. There were five or six students who were out at the time the fire commenced who lost all they had in the world except what they wore at the time. . . . The building burned from 4 to 7 o’clock when it was level with the ground.

Abner Austin also fought the fire.

The first thing I done was to holler fire and run to the engine house for the engine (the only one in town). Myself and another student burst the doors in with our feet and by that time there was enough there to help draw it over to the reservoir. I worked on it most of the time when I could get a chance but it did not do any good for the fire had got between the ceilings and we could not put it out any way. So we gave it up and begun to play onto the other [building] and also onto the wood pile and saved them. The Town Hall caught on fire & also another house close by but did not do any damage for there were men on both with pails of water ready to put it out.

Perry, whose optimism seems to have been matched by his sense of understatement, continued,

It was largely insured, and is attended with no very great loss, but considerable inconvenience. Mr. Williston has today made arrangements with the brick maker for the brick to build another Seminary, which will be larger and more commodious than the last and will probably be finished for use next fall term. We met this morning for prayers in the vestry of the church which will be used for that purpose for the present and also the recitation room for the Senior Class. Our recitations will go on as before as we recite in the other Seminary.

Samuel Williston’s new brick building, South Hall, would provide classrooms and dormitory space for nearly a century. Meanwhile Austin, like many of his friends, was profoundly shaken.

We go on with our school but in rather a cramped up way. . . . A part of the English scholars have gone home . . . Jake says he shall go home Monday if he gets some money to pay his bills, for his books was burnt and one of mine was too. . . . I think it my duty to leave school now for I am learning nothing but uglyness.

[For full texts, see “The Great Seminary Fire” and “Abner Austin, Fireman.”]

Abner Austin, like most students, turned to his parents for advice. So did Percy Lang, whose 1881 letter suggests an enviable confidence in both his mother’s judgment and in the college admission process.

I wish you would answer this question conclusively now. If I attend college, to which shall I go? Yale or Princeton? If I go to Yale I will graduate in 3 years; if P., I will get through in 4 years as the requirements are somewhat different for entrance. You will save me some trouble & time in deciding immediately. So please do. Perhaps that you desire that instead of which I go to a medical college instead. If so, please state that. I have a plan and that is this: that I study medicine next year & conclude in 3 yrs. then enter the navy for a 3 yrs. cruise as surgeon at a salary of $1800 per annum. By so doing I will obtain a knowledge of the world that I could not in any other way get.

Parental advice, of course, frequently came unasked. In May, 1873 Arthur Richmond’s mother admonished him,

I have no objection to your spending part of your time with the boys provided they are of the right sort and you know what that is as well as I can tell you for a boy is known by the company he keeps as well as a man and you must be very careful for I am not at your side to warn you, but there is one to whom you can go for guidance at all times, but I do not think it best for you to be from home at night. You are safest in the house and away from temptations for you know boys at least some are always getting into scrapes and they are very glad when they can get others to join them and that is one of the reasons that I wish you always to be home at night and do not hang around the village but whatever business you have to do, do it and go home.

A full year later, she was still at it:

I hope you are doing your best. You know your failing in being easily drawn away from any thing you undertake and I am not at your elbow to remind you so you must be on your guard least you forget when you have no one to remind you.

William Skinner’s father, writing in 1873, was more succinct:

You are old enough to know the value of time, and time lost can never be regained. Avoid any lazy beard growing loafer whose father has sent him to school to get him out of sight.

One can only guess how such parental concern was received. Abner Austin could not resist needling his father, “Did those segars smoke good that you took out of my trunk?” But it is telling that virtually every letter includes thoughts of home. Frank Davol, who had longed for his mother’s counsel when he struggled with his faith, wrote in December, 1867,

I was going to ask you if I could come home for Christmas but as we only have two days, I do not expect to come. You do not know how homesick I will be that day knowing that you will all have such a nice time and I so far away from home . . . This will be the first Christmas that I was ever away from home.

In 1856, Abner Austin missed his horse: “Tell Henry to take care of Old White good for I shall want to have him look pretty nice you know for it won’t look very well for a student to be riding around with an old poor horse.” And in 1842, Albert Montague’s longed for the family farm:

It has been a good hay day today. I wonder if our folks are haying. Wonder if they have got out the rest of the manure; wonder if Austin has took his steer, wonder if the water melons are all gone and last though not least wonder if the folks are all well . . . I wish I had some of Mother’s tea. I live well enough, though, and feel well, have not been homesick in the least.

Postscript: Frank Moore’s part in the bonfire never became known to local authorities. However, records in the Yale University Archives indicate he led a colorful career there. Percy Lang, or perhaps his mother, also chose Yale. Percy entered the banking profession rather than medicine. Abner Austin remained at home in North Haven, CT, where he managed the family farm. He eventually established successful livery stables and retail businesses in Meriden, CT. William C. Skinner became a leading manufacturer of silk textiles in Holyoke and South Hadley, Mass., and grew a beard.