At schools and colleges like Williston Northampton, one eye is necessarily on the future. Difficult as it is to predict the educational needs of the nation and the world a decade or a half-century hence, it is essential to try. As Williston itself very nearly learned in the 19th century, complacency is what closes private schools. It took a Headmaster of exceptional vision and perseverance, Joseph Henry Sawyer (who joined the faculty in 1866 and served as Head from 1896-1919) to break us of the habit of constantly looking backwards.

Details of Sawyer’s campaign for “The New Williston” are for another post. But briefly, it called for the development of the Williston Homestead property – our present campus – as the eventual replacement for the cramped and increasingly obsolete Old Campus in downtown Easthampton. There was a complete re-thinking of the role of the school and faculty in its students’ lives, from a kind of laissez-faire paternalism to active collaboration in academic, athletic, and social activity. To pay for all this, Sawyer sought new funding sources, notably through the then-controversial idea that a Williston education was only the beginning of an alumnus’s lifelong relationship with, and responsibility to, the school.

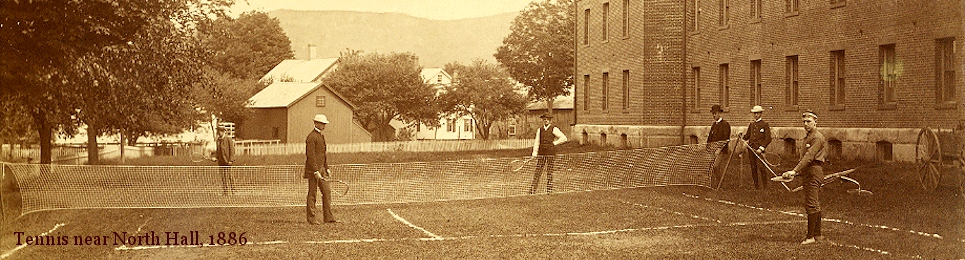

The transformation of the campus began with the creation of Sawyer Athletic Field in 1897-98 and the opening of Ford Hall in 1916. But the First World War, which brought with it an enrollment crisis that nearly closed an institution still far too dependent upon tuition income, put further building plans on the shelf. Sawyer, aged 77 and worn out by the strain of service, retired and died a few weeks later. It was left to his successor, Archibald Victor Galbraith (served 1919-1949), to revive the plans and bring them to the next level.

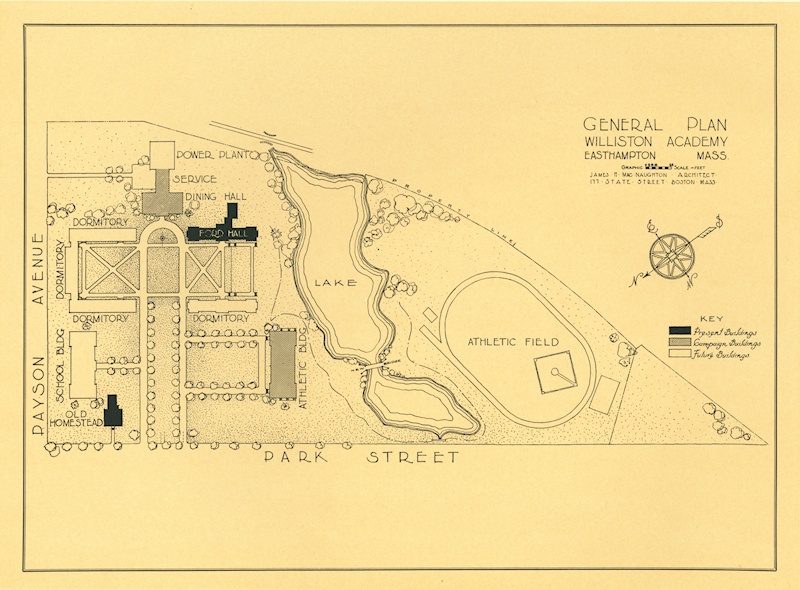

In 1927 Galbraith called on Boston architect James Hiram MacNaughton, class of 1909. As a student, MacNaughton had known Sawyer at his most enthusiastic and visionary. Galbraith’s first project was to build an innovative Recreation Center, a combination athletic, fine arts, and social building, that would supersede the school’s crumbling Old Gym, built in 1865. The building, which today dominates the south side of the Quad, was opened in May, 1930, just in time for the senior prom. (Few realize that its 1996 transformation to the Reed Campus Center restored its original function as a home for the arts and student activities.)

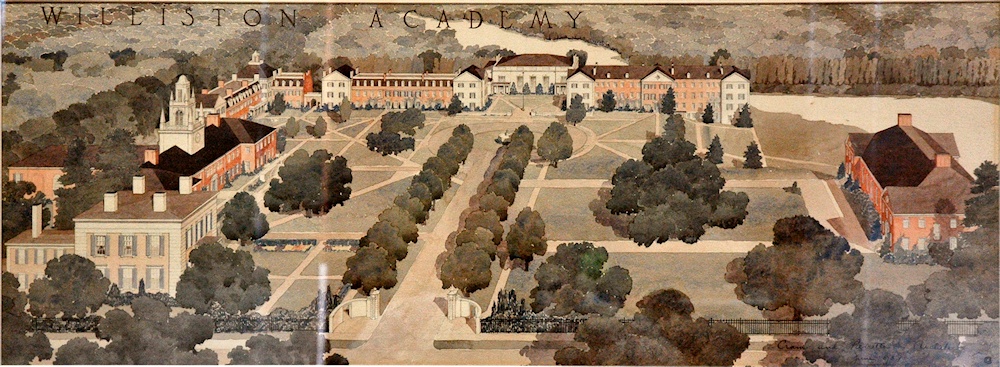

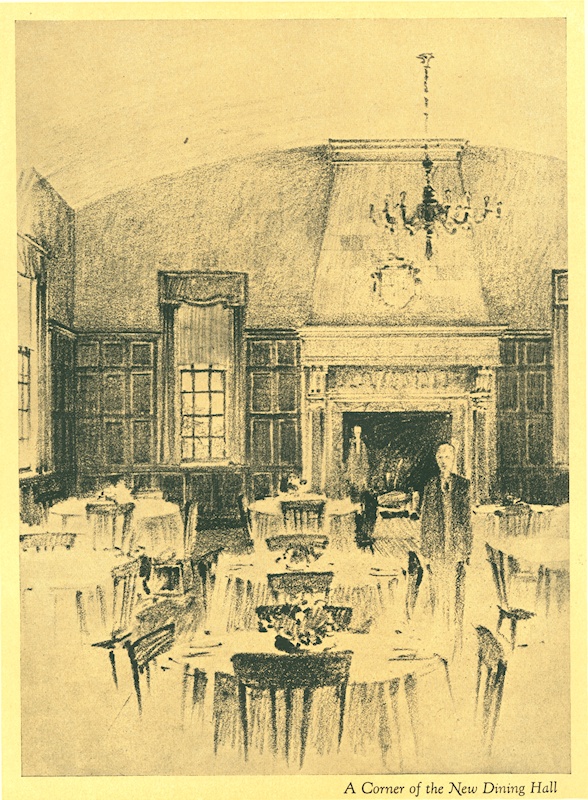

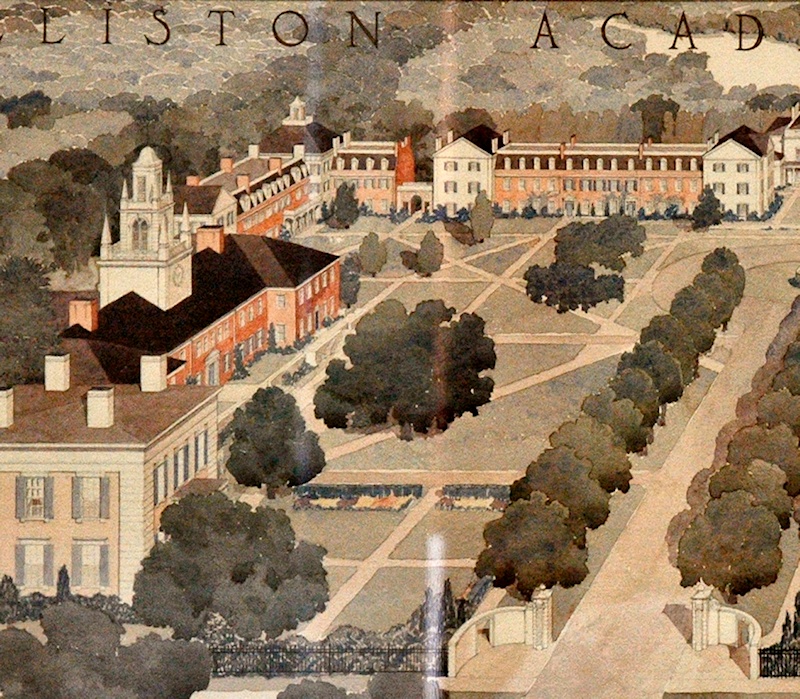

But along with the Recreation Center, Galbraith and the Board of Trustees asked for something broader: a master plan that envisioned how the campus might look in the future. Two additional buildings were intended for the near term: a dining hall and a classroom facility, to be called Memorial Hall. MacNaughton responded with an ambitious rendering of a series of interconnected buildings that would embrace the north and east sides of the Quadrangle, starting with Memorial Hall, just behind the Homestead, and ending with Ford Hall. The style would be “Georgian-Colonial, in keeping with Ford Hall.”

Construction of the Recreation Center began immediately, while the details of the next stages of the plan were presented as part of a 1928 fund-raising campaign. The hope was to move forward with additional buildings in time for the school’s centennial in 1941. No one could have anticipated that the collapse of the investment market in October of 1929 would plunge the country into a decade-long economic depression. Luckily, funds to complete the Recreation Center were already in hand, but work on other capital projects was suspended. World War Two would delay plans for the new campus even further.

The end of the War brought with it different academic and social, as well as fiscal priorities. The urgent need to consolidate the school onto the new campus as soon as possible was at the top of the agenda, but above and beyond its expense, the MacNaughton plan, now two decades old, seemed to invoke a vision of another time. And Headmaster Galbraith was retiring. It was left to his successor, Phillips Stevens (served 1949-1972), to bring about the change. The move was completed in 1951, having entailed the renovation of three factory buildings on Payson Avenue (two remain: Plimpton Hall and the Schoolhouse), and the construction of Memorial Dormitory on what was to have been the site of McNaughton’s Memorial Hall.

The Stevens era brought much expansion to the campus: the Science Building, Stevens Chapel, John Wright Dormitory, the Lossone Rink, plus construction of a dining hall wing on Ford Hall and the acquisition of several residential properties that would become small dorms. The large rendering of MacNaughton’s campus hangs in the Assistant Dean’s office where, for a variety of reasons, students are occasionally moved to contemplate that which might have been.

We encourage your questions and comments! Please use the form below.

Strange indeed to see a master plan of the present campus with leafless trees and a long 1950s auto parked. It must be that the Williston of today is a far more joyful place.

Good stuff, Rick. I hope other alums will contemplate the legacy from the past and the vision for the future. I am sure the “discovery” of some of this history by alums will strike a chord.

I remember old Mr. Galbraith. (and so many others: Mr. Shepherdson, Mr. Rouse, Mr. Lossone]). It seems so strange now in my advancing years that I was present for so much of this. As a kid I played, much to my mother’s dismay, in the clay and dirt on weekends with all of the neighborhood kids where they were building the science building and also in the old library extension (in the very foundations being excavated) back in the 1950s. I also remember the old wooden bridge across the Williston pond. Thanks for the memories, Rick. Neat stuff.