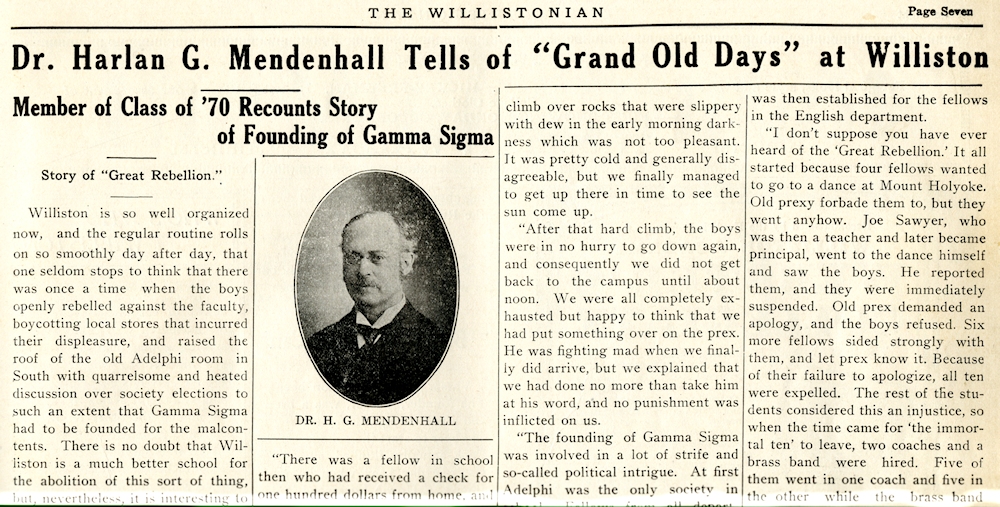

In the fall of 1931 the Reverend Dr. Harlan G. Mendenhall, Williston Seminary class of 1870 (Classical), visited the campus. Aged 80, Mendenhall was considered the “grand old man” of American Presbyterianism, having served in parishes all over the U.S., risen to the highest levels of the New York Presbytery, and was, in 1931, still not retired. Dr. Mendenhall brought with him a variety of documents from his student days, including a copy of the 1869 Salmagundi, Williston’s first senior yearbook, which he had co-edited, and a scrapbook of his student writings as a member of Adelphi, the school’s literary and debating society. He also sat down with The Willistonian for an extended interview, reproduced at length in the issue of October 21. Conversation focused on how the school had changed in more than five decades – and took a surprising turn.

“Williston in my day was a great deal different than your Williston of today. North Hall was but a few years old and was all partitioned off into three sections by thick fire walls. There were no bathrooms nor any central heating system, and in the winter we all had to buy our own coal for our stoves. We had no school dining room either and had to eat either at fraternity eating places or at the old “Hash Factory” which stood at the corner of Union and High Streets. It was possible to eat for two dollars a week then.”

“Students were then a great deal older than the fellows at Williston are now. There was one fellow named Redington who had already graduated from Yale and had come to Williston to study English. As the boys were older, they were more independent and often used to have revolutions and uprisings of all sorts.”

[Lyman William Redington of Waddington, N.Y. graduated Williston’s Classical Department in 1866. He completed a year at Yale, left because of eye problems, but returned to Williston and enrolled in the Scientific, a.k.a. English Department, graduating in 1869. He and Harlan Mendenhall were the founding co-editors of the yearbook Salmagundi in 1869. He became a newspaper editor in Rutland, Vt., ran unsuccessfully for Governor, took up law, and ultimately became Asst. Corporate Counsel for the City of New York, and a Tammany Hall member of the State Assembly.]

“There was a fellow in school then who had received a check for one hundred dollars from home, and instead of depositing it in the bank, he took it across to Putnam’s Book Store and established a checking account.”

“There came a time when Ballance, that was the boy, [William Henry Ballance, class of 1870] said that he had ten more dollars coming, and Old Put claimed that he had drawn his entire account. Then Ballance started an association of most of the boys in school swearing not to trade with Put until the ten dollars should be paid. They formed a big parade and marched down in front of Put’s store and read the constitution and by-laws of the association to him. Some of the boys carried big banners inscribed ‘No More Trade for Old Put’ and ‘False Weights Against True Ballance.’ The parade then marched over to the gym steps and had its picture taken.”

“Old Put remained adamant in spite of all these threats, and it turned out that very little ever came of it. For a week or so Put received no trade from Williston. Then gradually the boys began to drift in again and the whole incident was forgotten. Put was probably right, but the boys refused to believe that a storeman could be correct when one of their own number said that he was not.”

“I’ll never forget the time we went to see the sun rise from Mt. Tom. Some of the boys wanted to go and see the moon rise, but Prex Henshaw forbade it. [Principal (i.e. “Prex,” for “President”) Marshall Henshaw, served 1863-1876.] Then he jokingly said that we could go and see the sun rise if we wanted to. We took him at his word and started up the mountain about four o’clock the next morning. There was no road up there then, and we had to climb over rocks that were slippery with dew in the early morning darkness which was not too pleasant. It was pretty cold and generally disagreeable, but we finally managed to get up there in time to see the sun come up.”

“After that hard climb, the boys were in no hurry to go down again, and consequently we did not get back to the campus until about noon. We were all completely exhausted but happy to think that we had put one over on the Prex. He was fighting mad when we finally did arrive, but we explained that we had done no more than take him at his word, and no punishment was inflicted on us.”

“The founding of Gamma Sigma was involved in a lot of strife and so-called political intrigue. At first Adelphi was the only society in school. Fellows from all departments, English, Classical, and Scientific attended it, but it was always an unwritten law that a senior from the Classicals should be elected president. One year, however, the English students got together with the the Junior Classicals and put one of their own men, L. W. Redington, into the office. There was nothing that could be done about it as he had been legally elected, and so the Classicals had to be content.”

“Then came the time for a new election, and the English fellows, in conjunction with the Middle Classicals this time, again plotted to put one of their own men into the president’s chair. The Classicals, however, contrived a scheme to get one of their men in. Just before the meeting they rounded up a deciding number of Englishmen and offered to take them out to a cider mill. The Classicals took their unsuspecting victims out to the mill where they immediately left them and hurried back to the election. One of the Classicals was elected, and the meeting was just adjourning when the ‘kidnapped’ Englishmen suddenly put in their appearance.”

“They raised such a fuss that the faculty, who were meeting in a nearby classroom, rushed in to see what the trouble was. The Englishmen were so angry at being duped in this manner that a special meeting of the faculty had to be called later on to see what could be done. It was decided that the rival factions were so antagonistic that they could no longer remain in the same society; therefore, either Adelphi must be abolished or a new society must be formed. Gamma Sigma was then established for the fellows in the English department.”

[There is no question that the students in the Classical course had little respect for the Englishers (or Scientifics; the terms were interchangeable). Fundamentally, the Classicals, who dominated Adelphi (a debating and literary, as well as social, organization), considered their counterparts to be a gang of ignorant farm boys and manual laborers. Gamma Sigma rose from the Englishers’ efforts to prove them wrong. Joseph Sawyer, in his History of Williston Seminary (1912), tells the tale somewhat differently, but the essentials remain. The bitter rivalry transcended the founding of The Willistonian in 1881, which survived as a joint venture for exactly one issue, but also produced some brilliant joint debates until well into the 20th century.]

“We had only one system of punishment then. All miscreants were put in the old English schoolroom in Middle to study overtime under supervision. That was considered a severe punishment and the boys did their best to avoid it.”

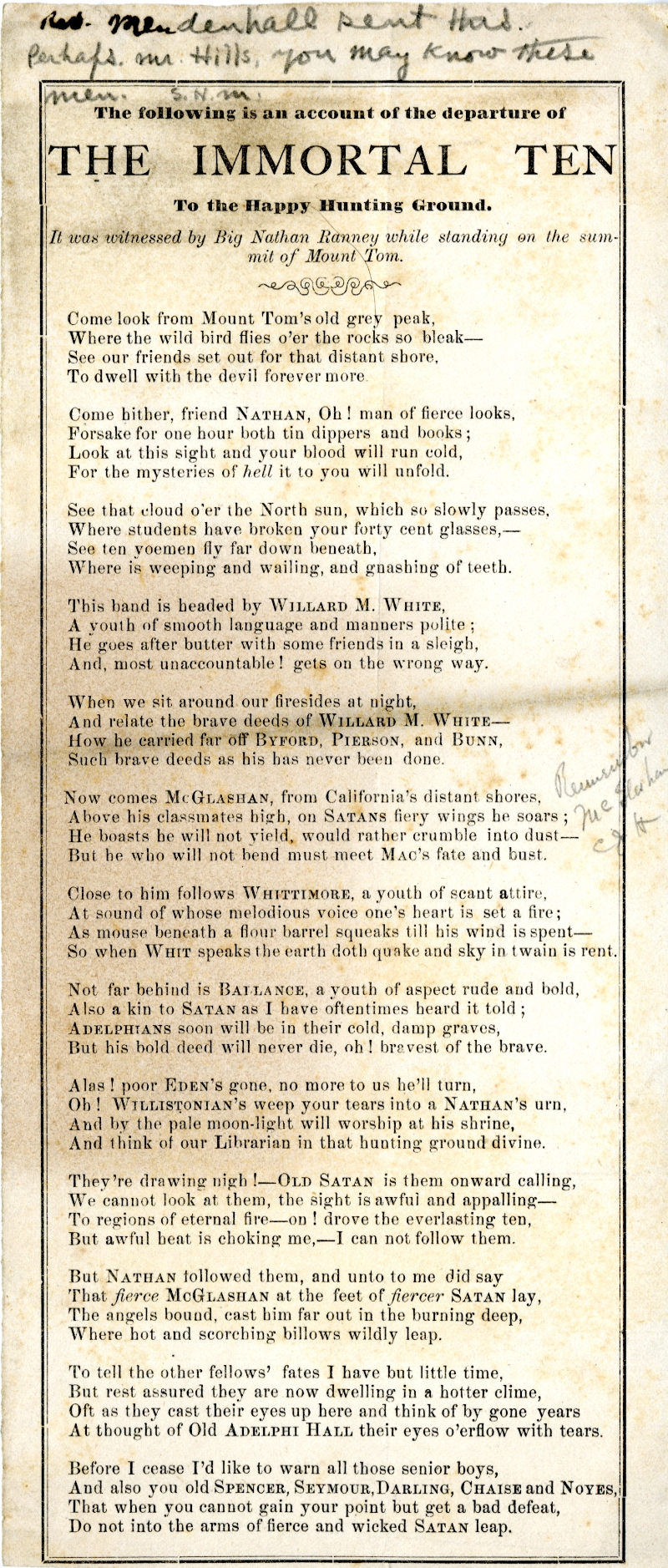

“I don’t suppose you have ever heard of the ‘Great Rebellion.’ It all started because four fellows wanted to go to a dance at Mount Holyoke. Old Prexy forbade them to, but they went anyhow. Joe Sawyer, who was then a teacher and later became principal, went to the dance himself and saw the boys. [Joseph Henry Sawyer joined the faculty in 1865 and served until 1919 — an astounding 54 years, including two appointments as Headmaster, 1884-86 and 1896-1919. While his behavior here might justifiably be considered hypocritical, it should be noted that at this time Sawyer was young and single, and no one had forbidden his being there.] He reported them, and they were immediately suspended. Old Prex demanded an apology, and the boys refused. Six more boys sided strongly with them, and let Prex know it. Because of their failure to apologize, all ten were expelled. The rest of the students considered this an injustice, so when the time came for ‘the immortal ten’ to leave, two coaches and a brass band were hired. Five of them went in once coach and five in the other while the brass band marched ahead. The whole school turned out and marched down to the depot with them. A long poem entitled ‘The Departure of the Immortal Ten to the Happy Hunting Grounds’ was written ‘as witnessed from Mount Tom by Big Nathan Ranney,’ who was the school janitor. This poem was a clever take-off on part of Dante’s ‘Inferno,’ and a cartoon was gotten up showing Joe Sawyer driving a carriage labeled ‘Williston on the road to ruin.’”

Perhaps it should be no surprise that records corroborating the Great Rebellion are hard to come by. It is even uncertain when this took place. When they can be identified, the names hinted at in the poem “Departure of the Immortal Ten” (reproduced at the end of this post) are all members of the classes of 1869 and 1870. But all are absent from the rosters in the Annual Catalogue of 1870, and none of the names appear in the Annual Exhibition programs — i.e., graduation — for either year, except Lyman Redington’s in 1869. Mendenhall does not appear either, and one is tempted to assume that he was expelled with the others. My best guess is that the mass expulsion took place in the early Spring of 1869.

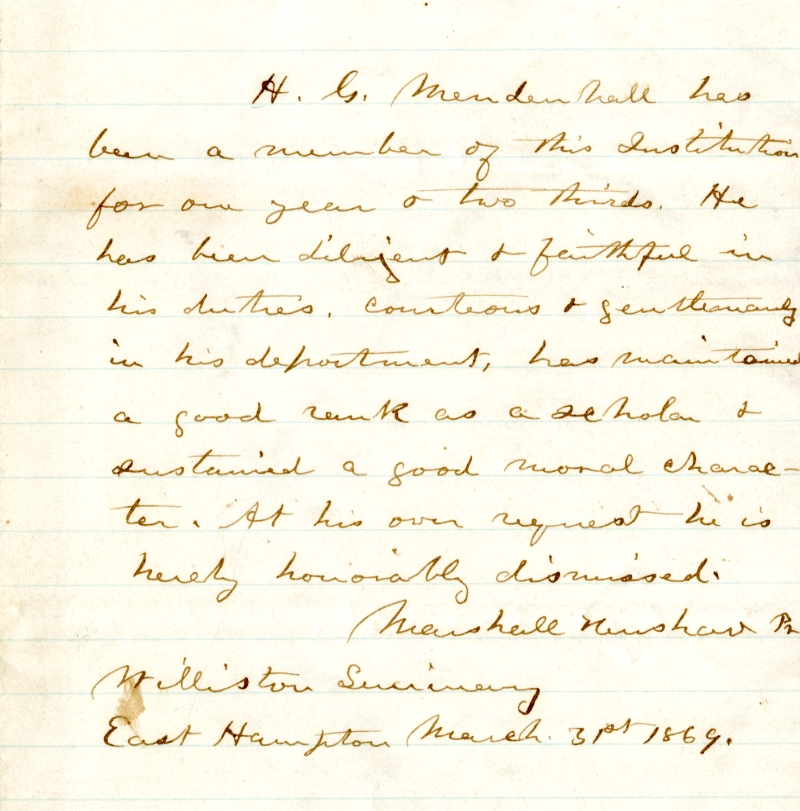

But what of Harlan Mendenhall? It turns out that he was not expelled; he resigned voluntarily in March of 1869. There is a letter of reference from Marshall Henshaw attesting to Mendenhall’s good character. But I wonder if he withdrew voluntarily, in protest over the treatment of his friends.

So why would a distinguished man of the cloth tell such stories after 55 years? Could it have been a kind of gleeful vengeance? We’ll probably never know.

Mendenhall’s gift to the school included an album of writings, primarily for the Adelphi magazine The Oracle, but also a selection of other writings that included poetry. He had a gift for parody versification, which lends credence to the possibility that “The Immortal Ten” is from Mendenhall’s pen. Alas, the cartoon of Sawyer driving on the Road to Ruin has not survived.

There is a wonderful series of letters written to “Mendie” by one of his roommates from North Hall, Joshua L. Pierson, from the time he left the Academy in 1869 through the early 1870s that I would be glad to share for your archives.

Thank you, Ed. I am replying via private email. — rlt