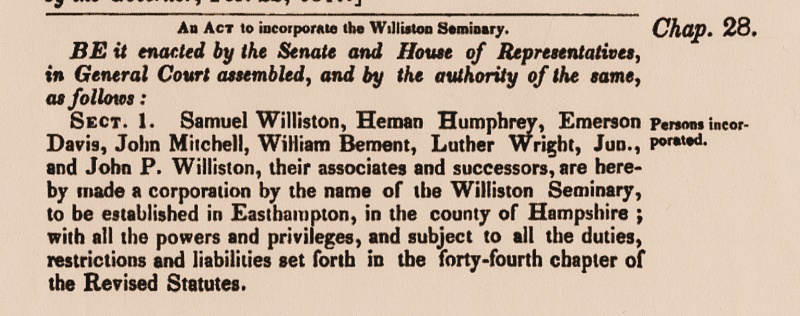

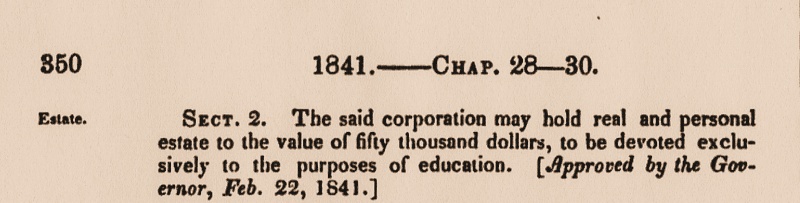

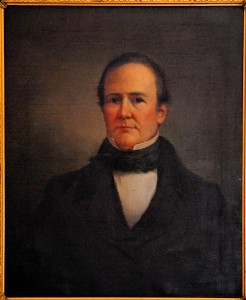

It was one small item from a legislative day filled with similar minutiae. But 175 years ago, Easthampton manufacturer Samuel Williston and a few associates petitioned the General Court to form a corporation “devoted exclusively to the purposes of education.” On February 22, 1841, the legislature approved the petition, Governor John Davis signed it into law, and Williston Seminary came into being.

Samuel Williston, like Governor Davis, was an influential member of the Whig Party — and Williston, perhaps conveniently, was a month into his only term as Easthampton’s Representative. Of the other incorporators, Heman Humphrey was President of Amherst College; Emerson Davis, Minister of the First Congregational Church in Westfield, Mass., John Mitchell, Pastor of the Edwards Church, Northampton; William Bement, Pastor of the Easthampton Congregational Church. Luther Wright (see 1848: Responding to the World) was Samuel’s boyhood friend, lately the Principal at Leicester Academy, and would serve as the Seminary’s first Principal. The only non-clergyman in the group was Samuel’s younger brother John Payson Williston (see Firebrand). These men would become the core of Williston Seminary’s first Board of Trustees.

Samuel Williston, like Governor Davis, was an influential member of the Whig Party — and Williston, perhaps conveniently, was a month into his only term as Easthampton’s Representative. Of the other incorporators, Heman Humphrey was President of Amherst College; Emerson Davis, Minister of the First Congregational Church in Westfield, Mass., John Mitchell, Pastor of the Edwards Church, Northampton; William Bement, Pastor of the Easthampton Congregational Church. Luther Wright (see 1848: Responding to the World) was Samuel’s boyhood friend, lately the Principal at Leicester Academy, and would serve as the Seminary’s first Principal. The only non-clergyman in the group was Samuel’s younger brother John Payson Williston (see Firebrand). These men would become the core of Williston Seminary’s first Board of Trustees.

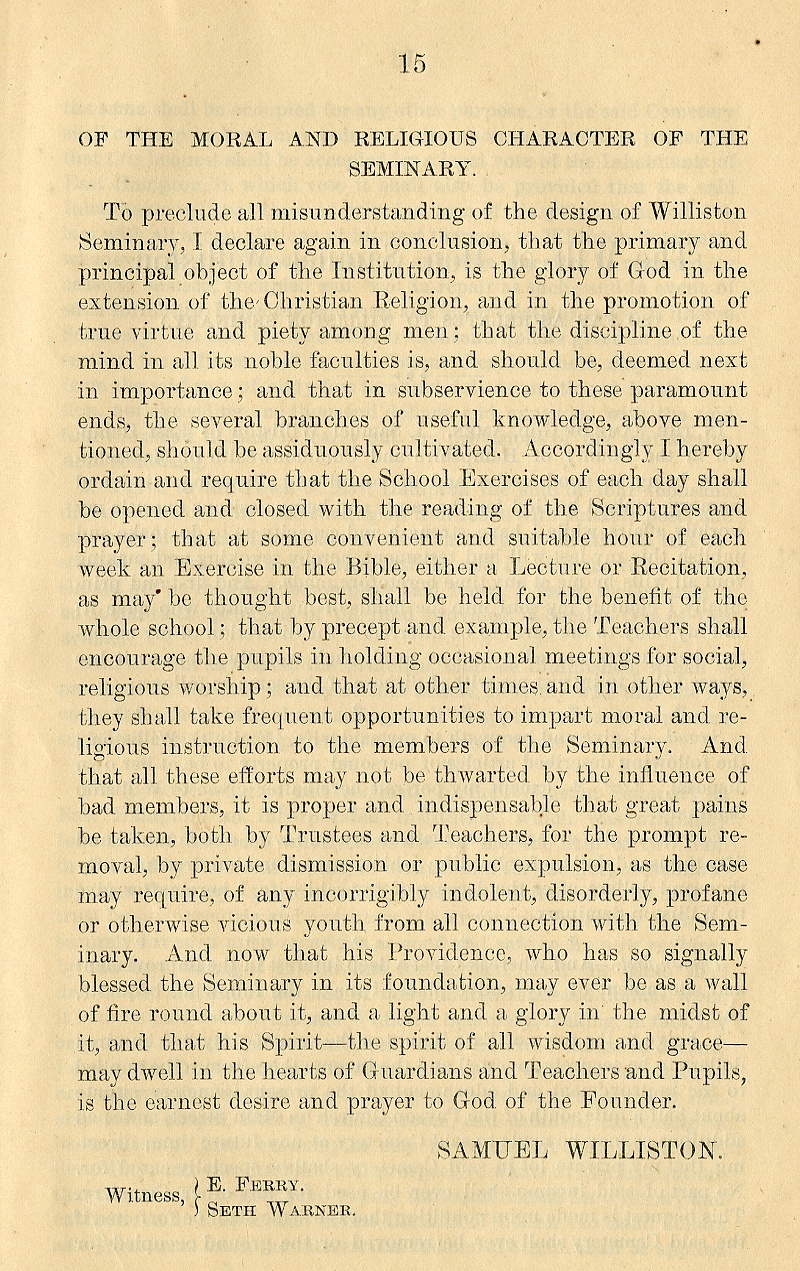

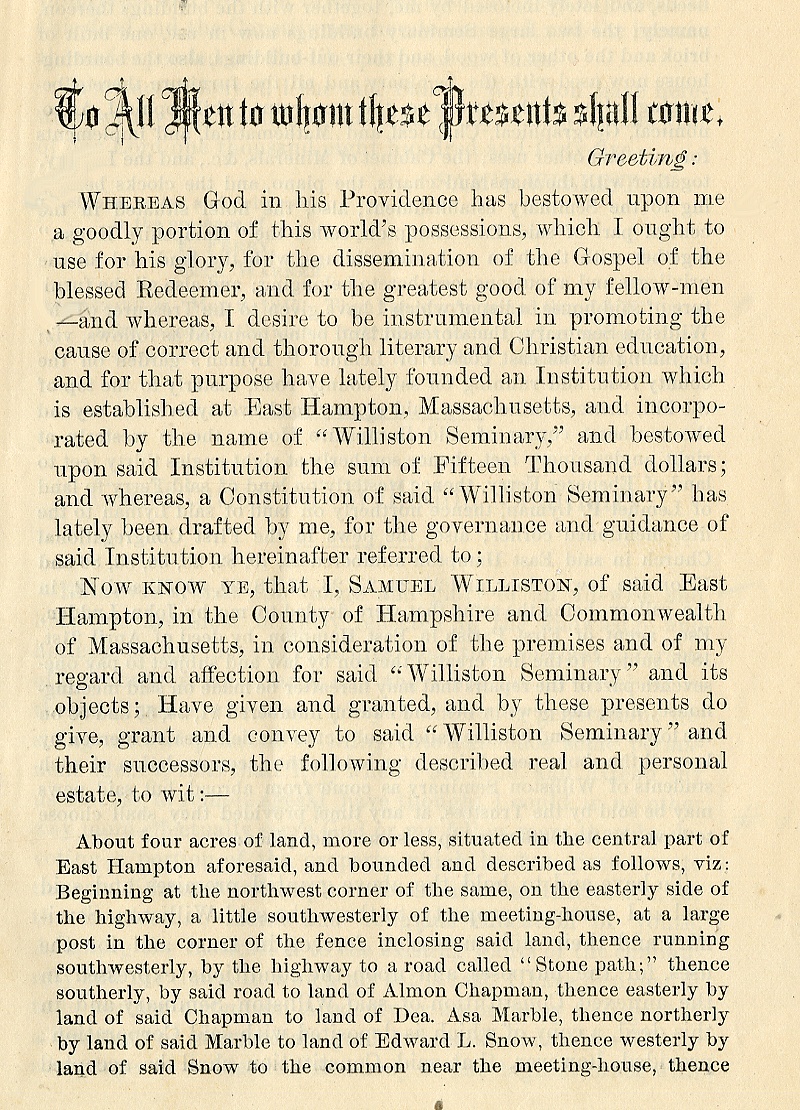

There was much to be done — indeed, it seems remarkable that ground would be broken for the first seminary building the following June 17, and that classes would meet in December. But consistent with their times, Williston and friends believed in action, sometimes at the expense of deliberation. Thus, it should perhaps be no surprise that Samuel Williston, who had strong feelings about education, took his time putting his thoughts to paper. But it needed to be done. Samuel expected his vision to provide direction to the Board and, as shall be seen, not only during his lifetime. A statement of mission was required. It took three years, but in 1845 Samuel Williston published The Constitution of Williston Seminary.

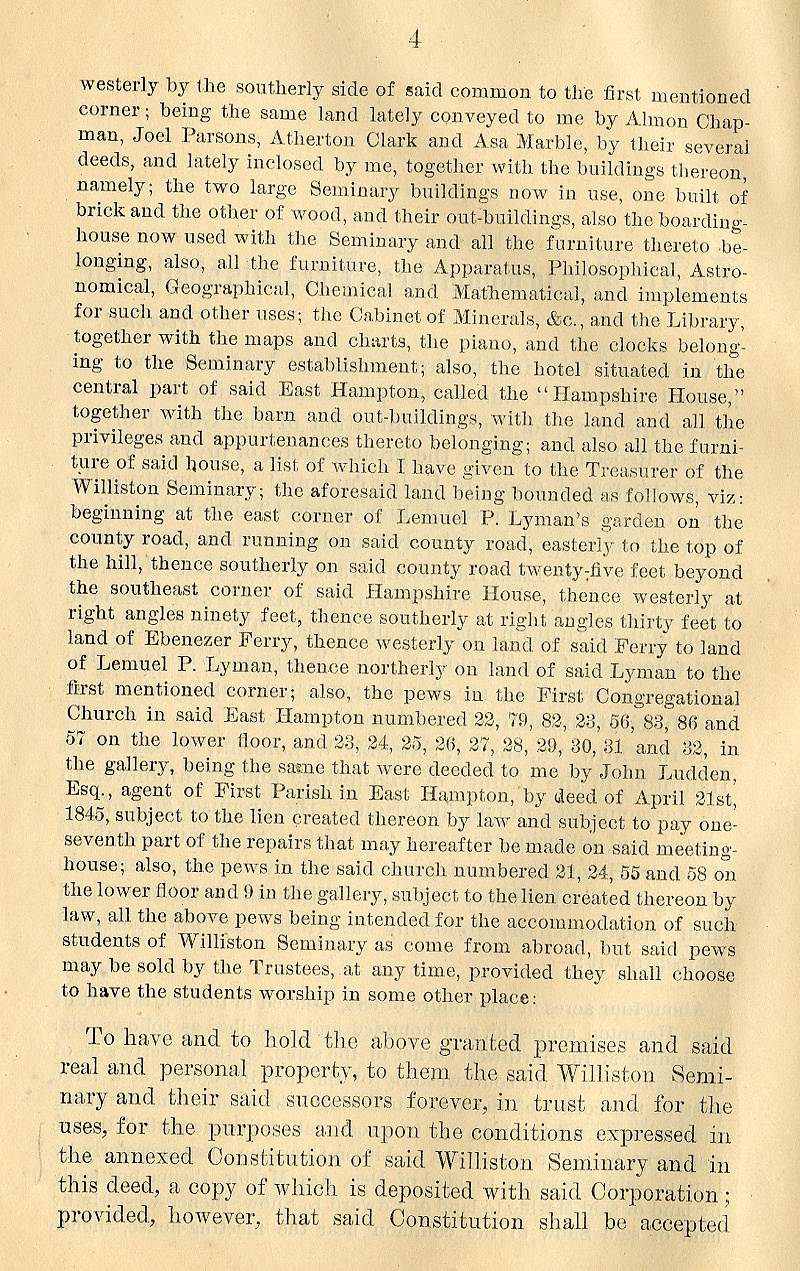

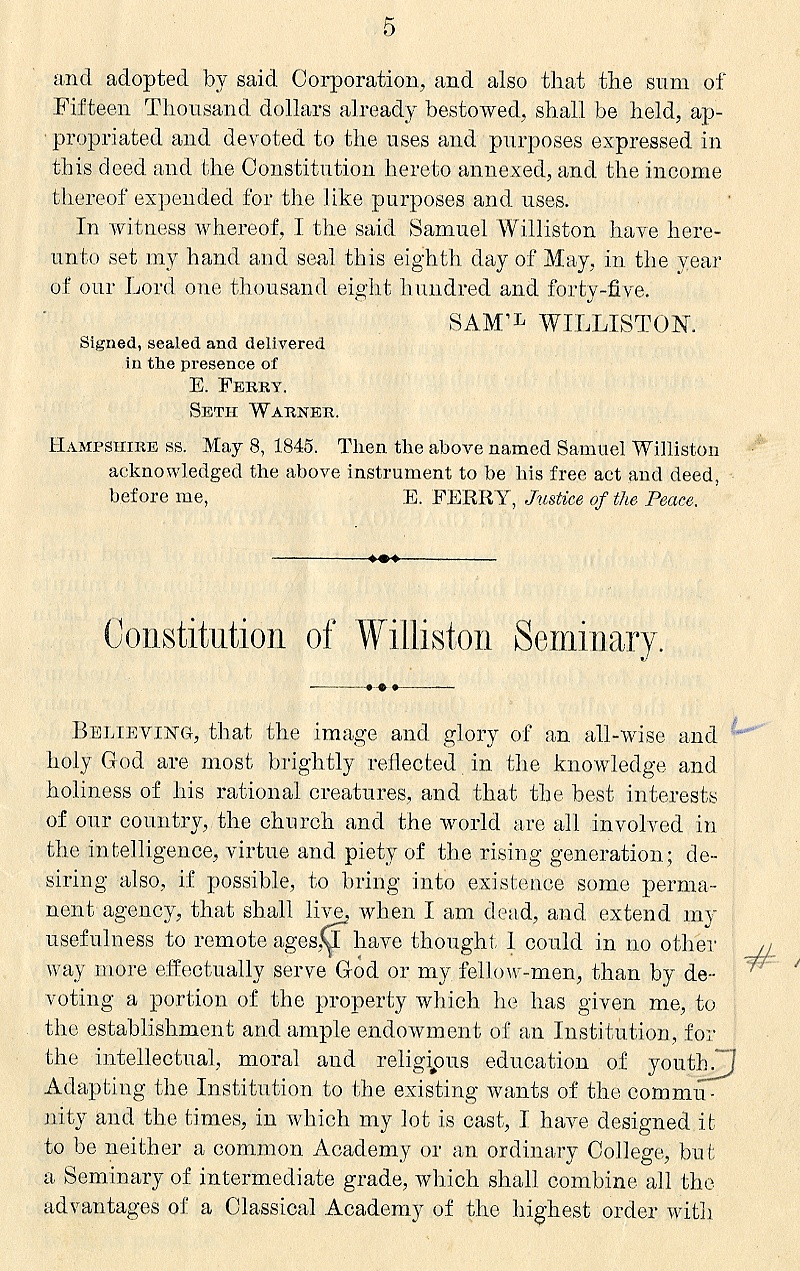

Only two copies of the 1845 print survive in the Archives, and they are too fragile to scan. But Williston’s plan was that his Constitution be provided to every future Trustee and faculty member, and that after he was gone, the text be read at Board meetings (see page 11). Thus, it was periodically reprinted, word for word. The reprinting continued until 1955; oral recitation was discontinued somewhat earlier. The edition reproduced below appeared in 1875. While this is far more text than is perhaps the norm for blog publication, those who read it in full will be rewarded with insight into the vision — and yes, the prejudices — of Williston Northampton’s founder.

Note: Williston describes the boundaries of the so-called Old Campus on Main Street, where the school was situated until 1951. It seems worth noting that Samuel Williston provided for segregated seating “students . . . as come from abroad,” presumably non-Christians. Despite his personal religious convictions, expressed throughout this document, the Seminary welcomed students regardless of their faith — provided they attended Christian worship.

It seems worth noting that Samuel Williston provided for segregated seating “students . . . as come from abroad,” presumably non-Christians. Despite his personal religious convictions, expressed throughout this document, the Seminary welcomed students regardless of their faith — provided they attended Christian worship.

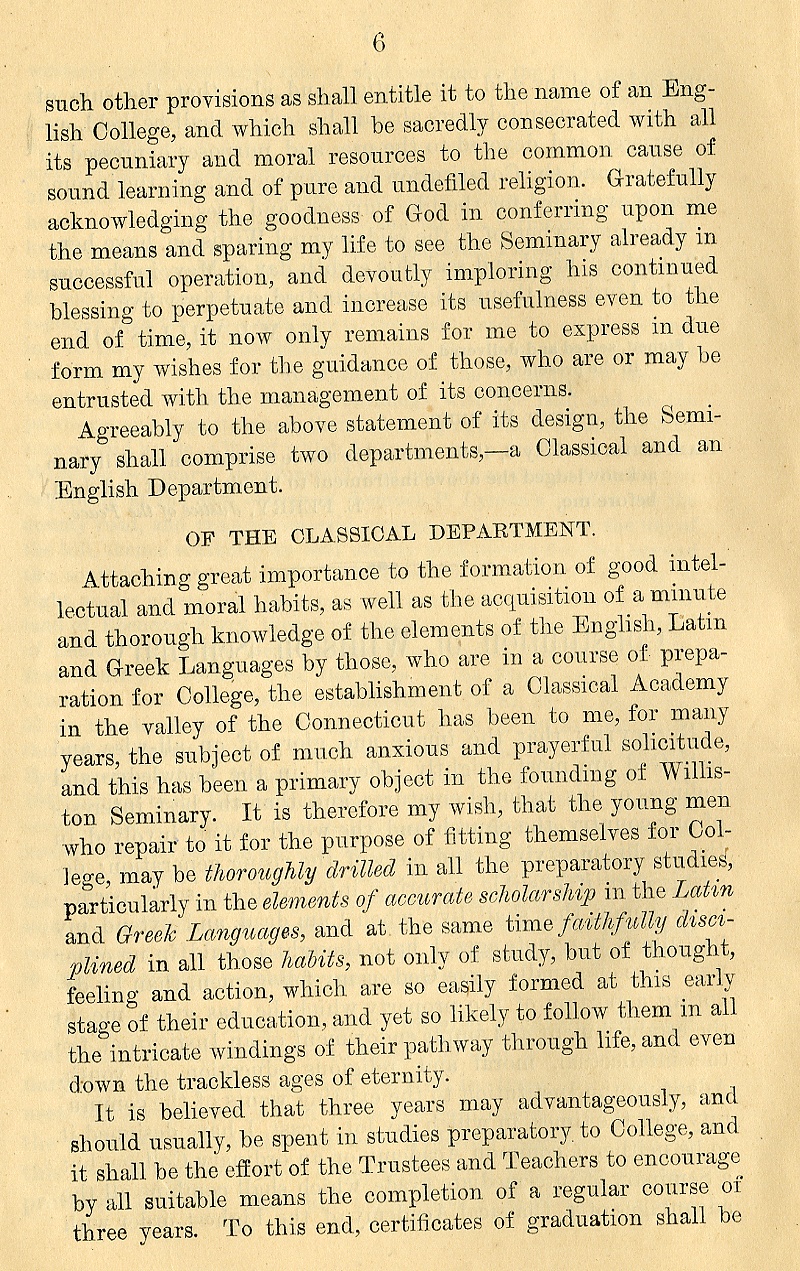

By “English” Department Williston meant “Scientific,” as the department would eventually come to be called. The name arose in part from Williston’s concept of an “English College,” modeled on the Rugby School in Britain (although Sam’s conception of Rugby was based on certain inaccurate assumptions), and in part from the language of instruction, which eschewed Latin and Greek.

By “English” Department Williston meant “Scientific,” as the department would eventually come to be called. The name arose in part from Williston’s concept of an “English College,” modeled on the Rugby School in Britain (although Sam’s conception of Rugby was based on certain inaccurate assumptions), and in part from the language of instruction, which eschewed Latin and Greek. “The community seem not yet to be fully prepared for such a course”: Williston’s English or Scientific Academy turned out to be a slow starter. As late as 1863, in a conversation with Principal Marshall Henshaw, he expressed his frustration with the division’s failure to thrive — “no better than a country high school.” Henshaw had to talk Samuel out of closing the Seminary, before successfully turning the program around.

“The community seem not yet to be fully prepared for such a course”: Williston’s English or Scientific Academy turned out to be a slow starter. As late as 1863, in a conversation with Principal Marshall Henshaw, he expressed his frustration with the division’s failure to thrive — “no better than a country high school.” Henshaw had to talk Samuel out of closing the Seminary, before successfully turning the program around. On the subject of coeducation, Williston was prevaricating; he had never been enthusiastic about the idea and was probably hypersensitive to observations that he wasn’t. But the Seminary’s Ladies’ Division was practical and politically advantageous, as long as Easthampton had no public secondary schools. In 1864 Williston built the town’s first public high school, and installed his “Female Teacher” as its Principal. At this time the Seminary became all-male. It would remain so for more than a century.

On the subject of coeducation, Williston was prevaricating; he had never been enthusiastic about the idea and was probably hypersensitive to observations that he wasn’t. But the Seminary’s Ladies’ Division was practical and politically advantageous, as long as Easthampton had no public secondary schools. In 1864 Williston built the town’s first public high school, and installed his “Female Teacher” as its Principal. At this time the Seminary became all-male. It would remain so for more than a century. The “College” and the “Female Seminary” were, respectively, Amherst and Mount Holyoke. Samuel was a Trustee and major benefactor of the former, and had provided much of the capital to found the latter.

The “College” and the “Female Seminary” were, respectively, Amherst and Mount Holyoke. Samuel was a Trustee and major benefactor of the former, and had provided much of the capital to found the latter.

Of interest is the idea that the Board was directly responsible for the hiring and potential dismissal of teachers. As a practical matter, that must have been delegated to the Principal at an early date. The requirement that the Principal and faculty be professed Christians was gradually abandoned by the mid-twentieth century; however, even as late as the 1960s there were no faculty who professed any other religions.

Of interest is the idea that the Board was directly responsible for the hiring and potential dismissal of teachers. As a practical matter, that must have been delegated to the Principal at an early date. The requirement that the Principal and faculty be professed Christians was gradually abandoned by the mid-twentieth century; however, even as late as the 1960s there were no faculty who professed any other religions. “Goodness without knowledge . . .” Samuel Williston cribbed this from the 1798 Constitution of Phillips Academy in Andover, where he had briefly enrolled. Samuel Phillips’ text reads, “Goodness without knowledge . . . is weak and feeble; yet knowledge without goodness is dangerous; and that both united form the noblest character, and lay the surest foundation of usefulness to mankind.” It is arguable that Williston got the idea of a school constitution from the Andover model.

“Goodness without knowledge . . .” Samuel Williston cribbed this from the 1798 Constitution of Phillips Academy in Andover, where he had briefly enrolled. Samuel Phillips’ text reads, “Goodness without knowledge . . . is weak and feeble; yet knowledge without goodness is dangerous; and that both united form the noblest character, and lay the surest foundation of usefulness to mankind.” It is arguable that Williston got the idea of a school constitution from the Andover model. Samuel blew hot and cold on the issue of Temperance at different times in his life. This must have been one of the warmer times. At no time prior to the construction of Ford Hall in 1916 was the school able to provide housing for all its students, nor did the institution provide meals. Students, even those residing in school housing, formed eating-clubs in local hotels and boarding houses.

Samuel blew hot and cold on the issue of Temperance at different times in his life. This must have been one of the warmer times. At no time prior to the construction of Ford Hall in 1916 was the school able to provide housing for all its students, nor did the institution provide meals. Students, even those residing in school housing, formed eating-clubs in local hotels and boarding houses. See the note following page 11. Despite his “Protestants only” dictum, beyond the Seminary Samuel was tolerant of and even generous to Catholics, and went as far as providing land and financial assistance to Easthampton’s first Catholic parish.

See the note following page 11. Despite his “Protestants only” dictum, beyond the Seminary Samuel was tolerant of and even generous to Catholics, and went as far as providing land and financial assistance to Easthampton’s first Catholic parish.