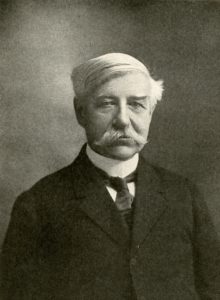

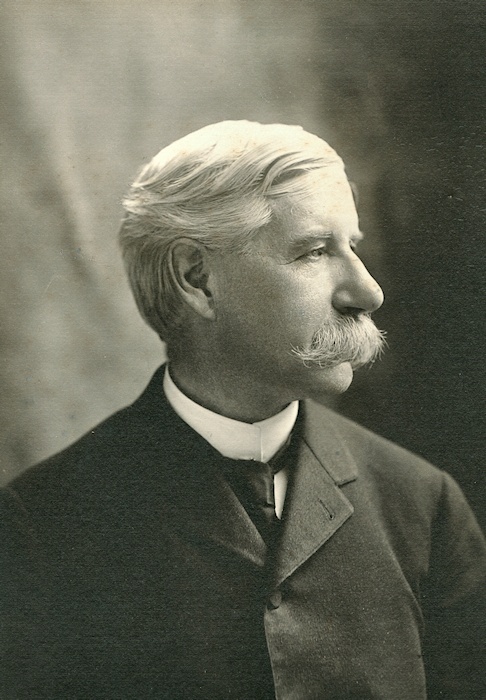

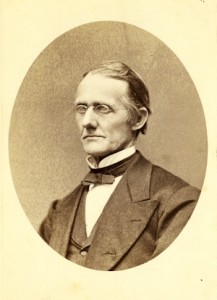

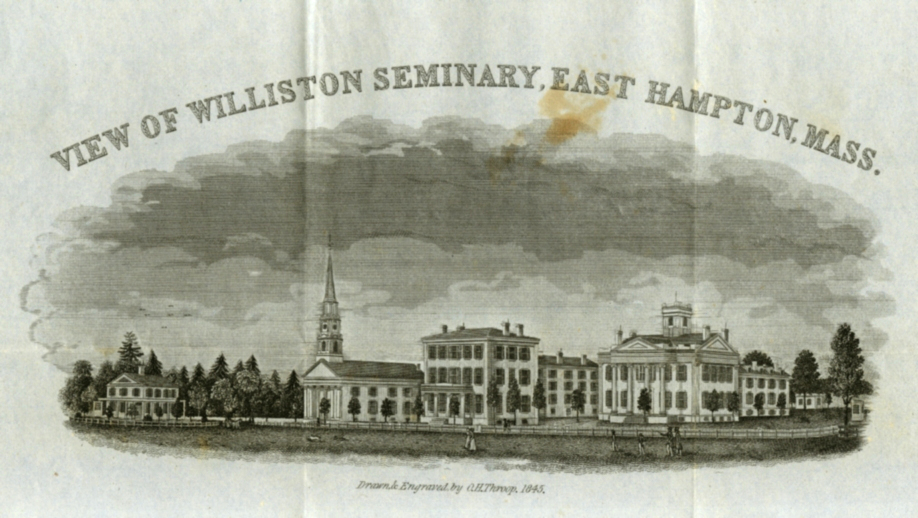

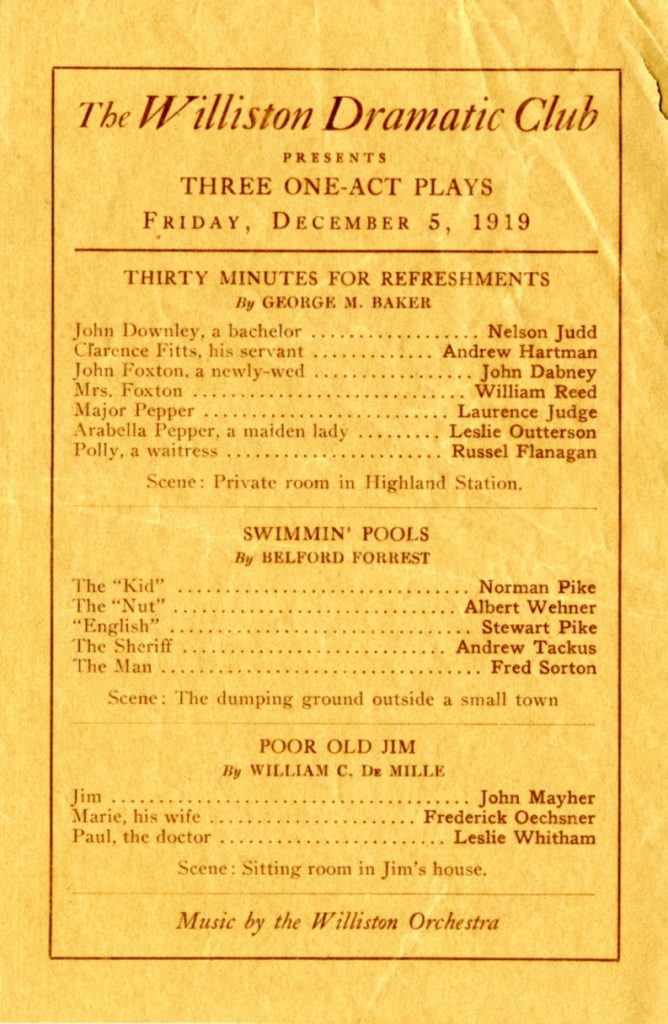

In 1918-1919, the final year of Headmaster Joseph Sawyer’s administration, Williston Seminary’s outlook appeared bleak. Sawyer had been Principal since 1896, and on the faculty since 1866. Aged 77, he had been at Williston his entire adult life. Under his leadership, a vision for a different kind of school had evolved, but little had actually been done about it. Much of his effort had been in fund-raising, in which he had little experience, and for which, little taste. He had undertaken significant financial reforms at home. It was working: enrollment had stabilized, the deficits were shrinking, and Ford Hall had been opened in 1916. But the First World War changed everything. Enrollment, and with it income, plunged; deficits soared. Sawyer closed dormitories and tightened belts. Still, by the time the Armistice was signed in November, 1918, only 13 seniors remained. Depressed and in poor health, Sawyer announced his resignation in June 1919, effective as soon as a replacement could be found. (For Sawyer’s story, see Visionary Keeper of the Flame.)

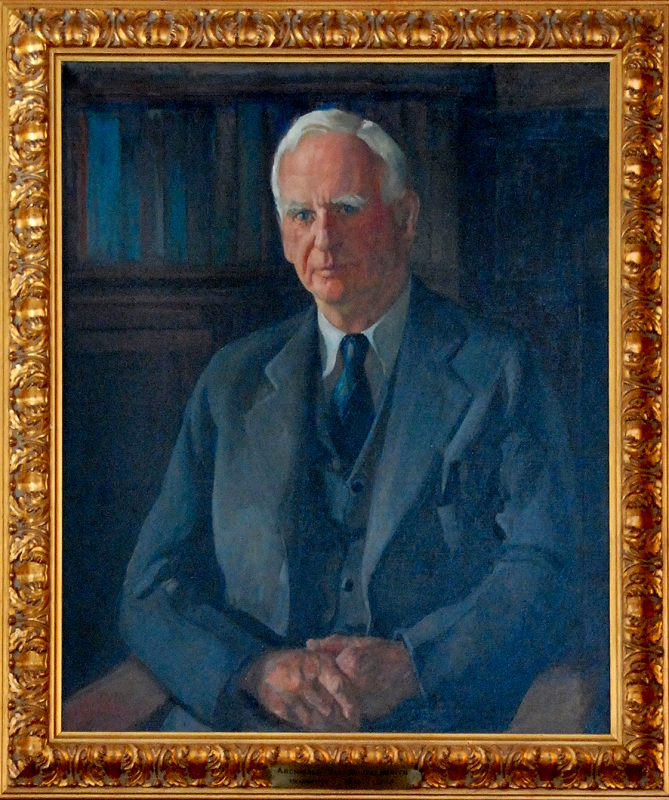

Williston had hired Principals on short notice before. Sawyer himself had been among them. The 1919 timetable appeared open-ended: Sawyer would remain Head, assist with the transition, and then move over to the Board of Trustees. But those who knew him well probably sensed that there wasn’t much time. We are not sure why Archibald Galbraith was approached. Galbraith had been teaching mathematics at the Middlesex School in Concord, Massachusetts, for 16 years. Aside from a few years as Athletic Director, and service as a dormitory head, he had relatively little administrative experience. In his own words, he “had no other plan than to continue there.” (GY, 8). But someone must have had good instincts. In July, Trustees Robert P. Clapp ‘75 (for whom the present campus library is named) and John L. Hall ‘90 met with Galbraith and convinced him of the “challenging opportunity for real service, one which [he] believed [he] was able to do.” (GY, 9) Middlesex Headmaster Frederick Winsor was supportive, and in due course, Galbraith accepted the position.

As things transpired, Galbraith would have only one meeting with Sawyer, who by this time was too sick even to move out of the Homestead. Instead, the Galbraiths moved into temporary faculty quarters in Ford Hall. Sawyer lingered a few weeks and died, worn out in service to his school, on November 7, 1919.

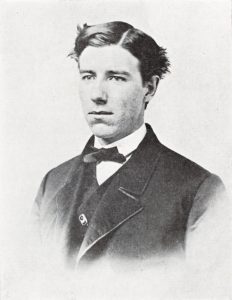

Archibald Victor Galbraith was born in Boxford, Mass., in 1877, and grew up in California and in Springfield, Mass. He was an 1895 honors graduate of Springfield High School, attended Harvard, where he concentrated in mathematics, was elected to Phi Beta Kappa as a junior, and received the Bachelor of Arts degree, magna cum laude, in 1899. At Harvard he also excelled in athletics, particularly baseball. (According to legend, which Harvard authorities have so far been unwilling or unable to confirm, he was the only Harvard shortstop ever to execute an unassisted triple play.) After graduation he taught and coached at Milton Academy for one year, then three more at the William Penn Charter School in Philadelphia, before he joined the Middlesex faculty. He married Helen McIntosh, of Newton, Mass. in 1905. Arch and Helen spent 1905-06 in Munich, where he pursued graduate courses. They also traveled extensively on the Continent for a year, before returning to Middlesex. They had two sons, Frederic ‘23, and Douglas ‘33.

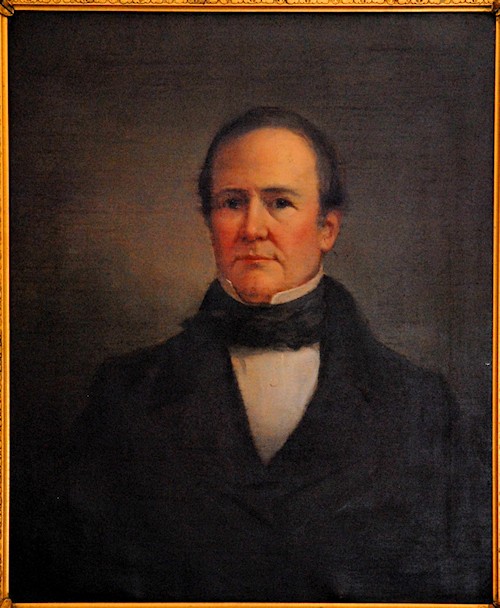

When Galbraith arrived at Williston, he discovered a school which, in his words, was administratively “not fundamentally different from what it must have been during its formative years.” (GY, 11) For seventy years the Board, largely made up of the Founder’s friends and relations or their descendants, had labored to keep Samuel Williston’s vision alive, even as the educational needs of the country and the expectations of colleges had changed. There had been some migration away from this in recent decades – but certain Trustees were aware that it was not enough. Notably, John L. Hall ‘90, who had initially approached Galbraith, at age 47 represented the youth movement on the Board, while Clapp lived not far from the Middlesex School and may well have known Galbraith socially. They appear to have found a surprise ally in Robert L. Williston ‘88, Samuel Williston’s grand-nephew, but at 50, another relatively young Trustee.

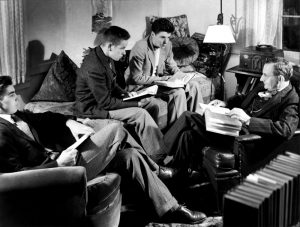

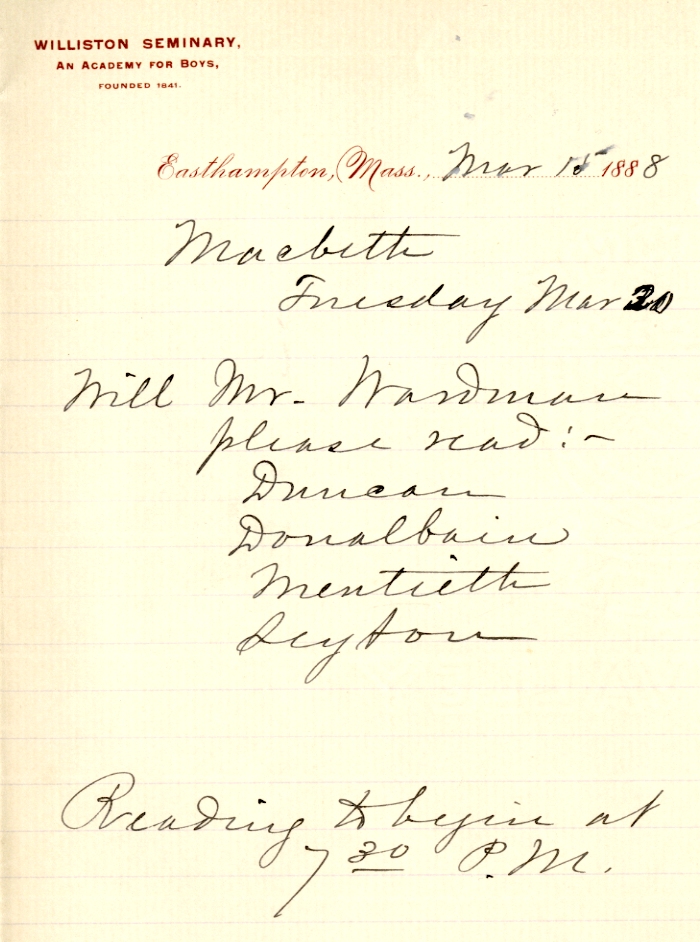

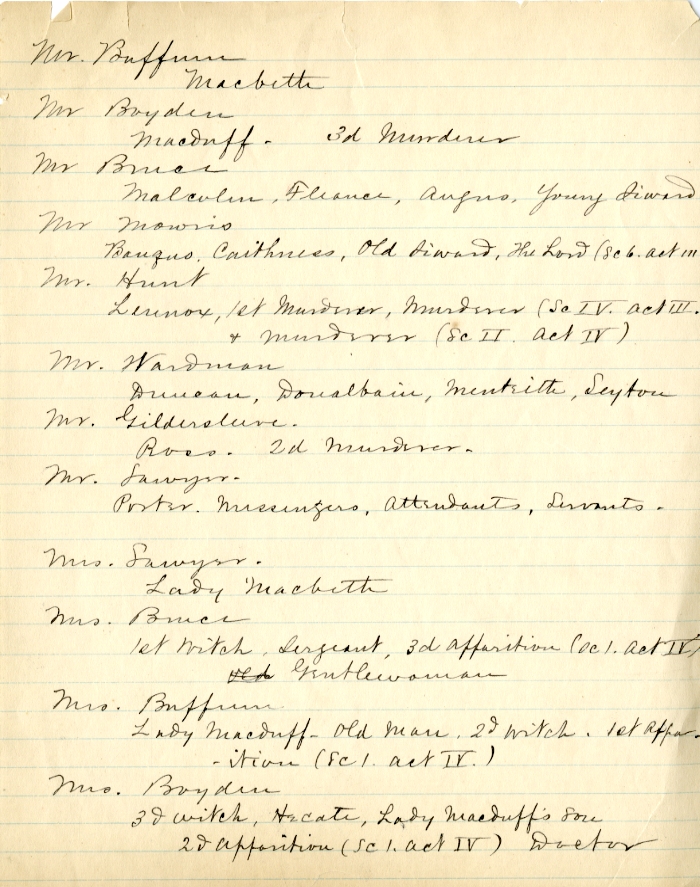

Galbraith inherited a strong faculty, led by Charles A. Buffum (Latin and Greek), Sidney Nelson Morse (English), and the extraordinary George Parsons Tibbets (Mathematics). Several other exceptional teachers were in early or mid-career: George Hero (History), Lincoln D. Grannis (Latin and Greek), Melvin J. Cook (Math), and Earl Nelson Johnston (Science) – the last three are very much alive in the memories of alumni from the thirties and forties. But faculty roles were, by longstanding tradition and preference, largely bounded by the walls of the classroom. Galbraith observed that even Tibbets, innovator though he was, expended most of his attention on his more talented students. Although Sawyer’s writings on “The New Williston” had called for a greater role for the faculty in student life, nothing had been done. The situation was in startling contrast to that at Middlesex.

Continue reading