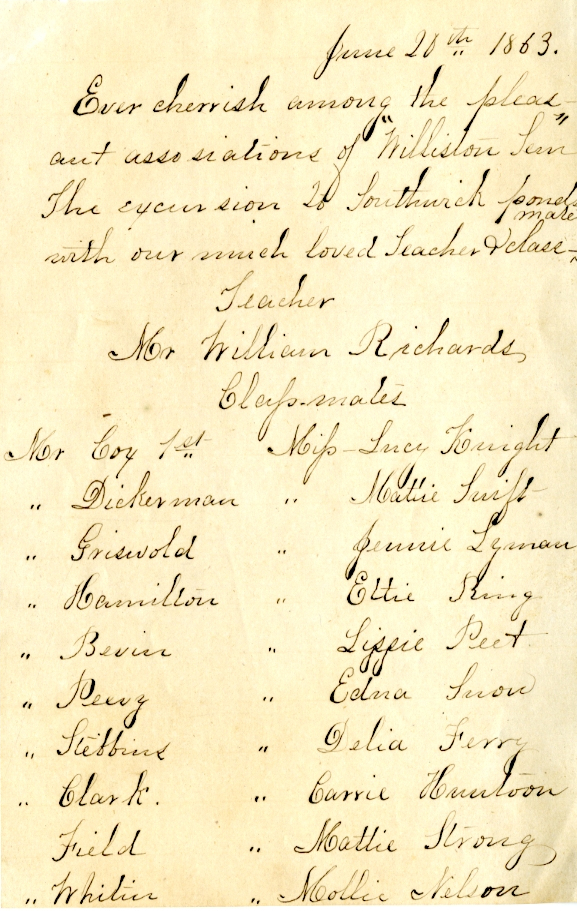

It was a sunny Saturday, June 20, 1863. The term was almost over; students and teachers were about to disperse. With the papers full of news of Civil War hostilities, alumni and family members gone South to fight, there was an overtone of uncertainty about the future. But for at least a day’s respite, twenty Williston students — ten young men and ten young ladies — went on a plant collecting expedition — “botanizing,” as they called it — to Southwick, about ten miles from Easthampton. How much of this was serious scientific pursuit and how much an excuse for a picnic, we will never know. Even at still-coeducational Williston Seminary (the Ladies’ Department would be closed in 1864), opportunities for mixed social activity were few.

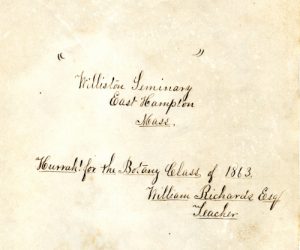

The organizer and chaperone was William Austin Richards, Williston 1855, Amherst ’61, who upon his graduation had returned to Williston as a teacher of Latin and Greek. Richards planned to teach for a few years to gain a little experience and cash, before studying for the ministry. None of his Williston responsibilities included anything scientific; natural history must have been merely an avocation. And although a document refers to the “botany class,” there was no formal course in the Williston catalogue. Nonetheless, at least some of the students took the scientific side of the day very seriously.

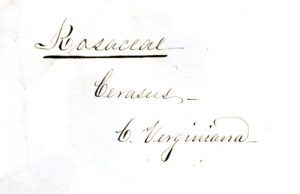

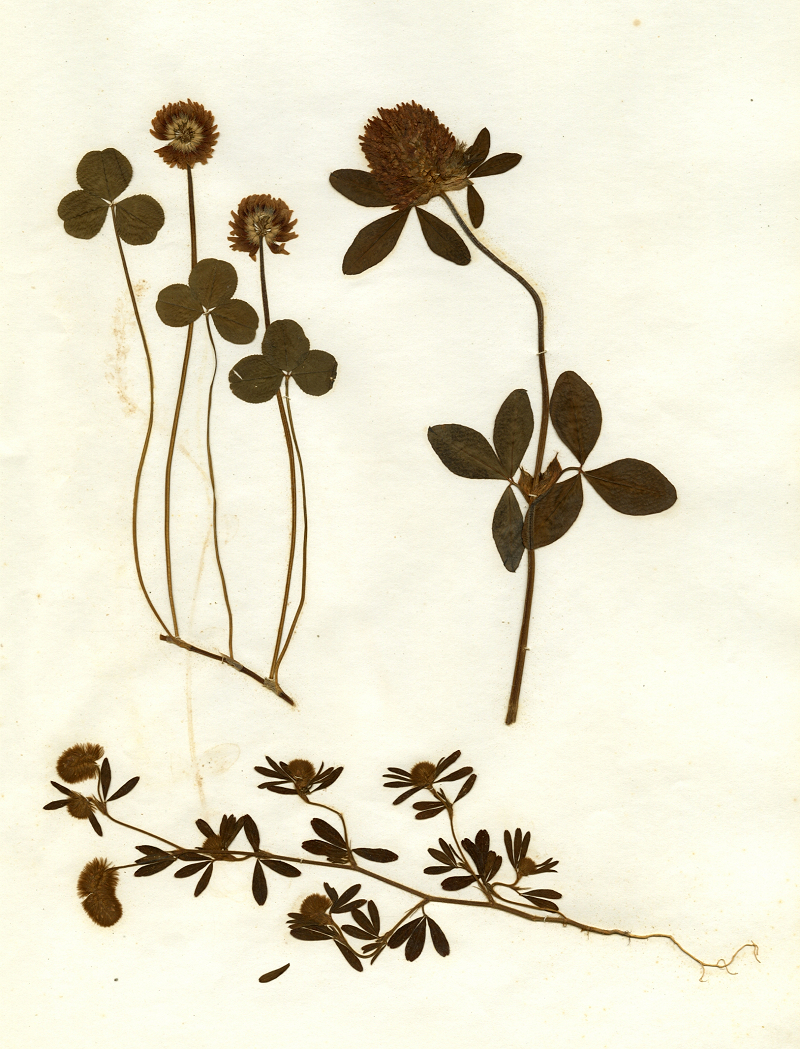

One of these was Mary Lydia Nelson — “Mollie” — a senior from West Suffield, CT. Mollie went home and meticulously pressed the day’s collection of plants. Almost unbelievably, 154 years later, her specimens remain in nearly pristine condition. Mollie did everything right. There are 57 folders, each a sheet of paper 23 x 18 inches (11.5 x 18″ folded.) Mollie chose a very high quality heavyweight rag paper with almost no acid content, so there has been practically no chemical reaction between plants and paper. She secured each plant to the paper with nearly invisible white cotton thread. Almost every specimen was carefully labeled with phylum, genus, and species.

Mollie retained her plant collection as a cherished keepsake. It stayed in her family and against all odds, was always well stored, away from extremes of temperature and humidity. In 1983 Mrs. J. R. Nelson, widow of one of Mollie’s descendants, presented the collection to Williston Northampton.

Recently this writer had occasion to show the plants to Jane Lucia’s 7th grade science and upper school Outdoor Ecology classes. We asked why, above and beyond school history, such a collection was significant? Some of the students’ ideas included tracking species distribution over time, perhaps as evidence of habitat or climate change. The specimens can be compared with present-day examples, to determine whether there has been evolutionary change. It may even be possible to extract DNA from the specimens.

Mollie Nelson’s collection also included a folder inscribed “Hurrah! for the Botany Class of 1863, William Richards, Esq., Teacher,” containing a laurel wreath and beribboned sprig of hemlock. It would appear that these, perhaps along with the “Ever cherish” note reproduced earlier, were to have been presented to Professor Richards in commemoration of the day. Why were they not? The sad answer is that Mollie never had the chance. For William Richards, visiting his brother during the summer holiday, contracted typhoid fever and died on September 7, 1863, aged only 27.

Here is a gallery of more of Molly Nelson’s botanical collection.

Thank you so much for putting together this lovely commemoration of “Mollie” Nelson’s botanical preservation efforts and sharing its story. What she did is exceedingly difficult to do well, taking meticulous attention to detail and heaps of patience. Here is a thought for you about the flower labeled “Unidentified Specimens”, appearing directly after the Aspidium spinulosum. Might it be Common Yarrow (Achillea millefolum)? It looks exceptionally close to the yarrow of today. It is something one would likely find in a sunny meadow where one would go picnicking. Not sure if you are looking for plant identification guesses, but there’s one for you!

I’m not a plant identification expert, so it was an easy editorial decision to include only Mollie Nelson’s identifications, adding only the modern common name and, where there have been changes, the present-day taxonomic name. Having covered myself with caveats, I think you may be correct. Incidentally, there’s a very good New England identification guide at Go Botany, that I found very useful.

Thanks for the positive feedback! — Rick

The link in my message of Nov. 4, 2017 has changed. It is now https://gobotany.nativeplanttrust.org/

Fascinating, and I think it’s great that you let students get up close to such treasures, rather than locking them away or putting them under glass. Although, isn’t that at bit dangerous? A question: why are you wearing gloves in the class photograph?

I’ve long felt that if the Archives aren’t available as a teaching resource, then we’re missing a wonderful opportunity to engage students. Trust me, when not in use, everything is securely locked away. The gloves are to prevent oils or moisture on my hands from transferring to the artifacts. Although one of my 12-year-olds asked whether I thought I was Michael Jackson. No, I replied, Mickey Mouse.