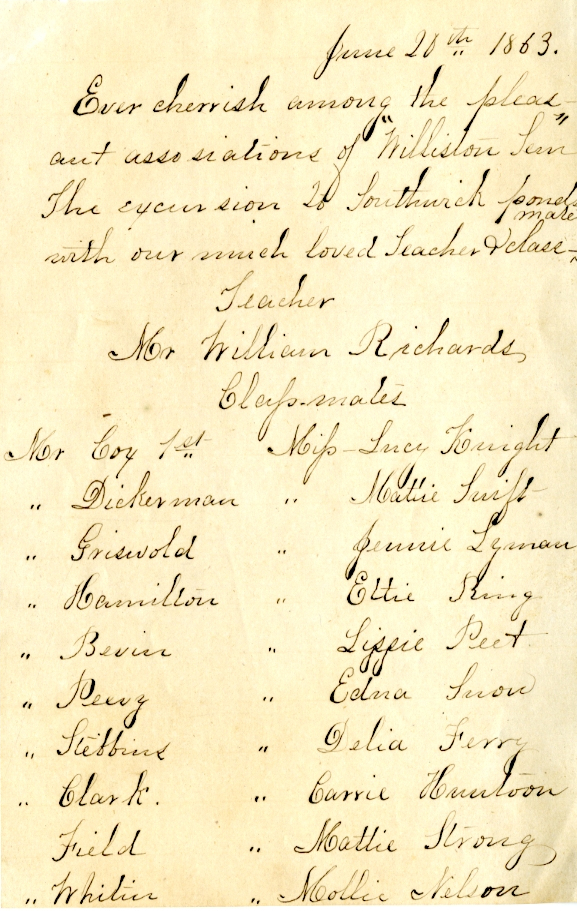

It was a sunny Saturday, June 20, 1863. The term was almost over; students and teachers were about to disperse. With the papers full of news of Civil War hostilities, alumni and family members gone South to fight, there was an overtone of uncertainty about the future. But for at least a day’s respite, twenty Williston students — ten young men and ten young ladies — went on a plant collecting expedition — “botanizing,” as they called it — to Southwick, about ten miles from Easthampton. How much of this was serious scientific pursuit and how much an excuse for a picnic, we will never know. Even at still-coeducational Williston Seminary (the Ladies’ Department would be closed in 1864), opportunities for mixed social activity were few.

The organizer and chaperone was William Austin Richards, Williston 1855, Amherst ’61, who upon his graduation had returned to Williston as a teacher of Latin and Greek. Richards planned to teach for a few years to gain a little experience and cash, before studying for the ministry. None of his Williston responsibilities included anything scientific; natural history must have been merely an avocation. And although a document refers to the “botany class,” there was no formal course in the Williston catalogue. Nonetheless, at least some of the students took the scientific side of the day very seriously.

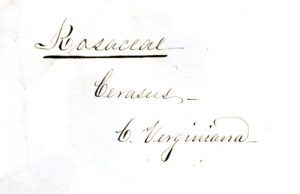

One of these was Mary Lydia Nelson — “Mollie” — a senior from West Suffield, CT. Mollie went home and meticulously pressed the day’s collection of plants. Almost unbelievably, 154 years later, her specimens remain in nearly pristine condition. Mollie did everything right. There are 57 folders, each a sheet of paper 23 x 18 inches (11.5 x 18″ folded.) Mollie chose a very high quality heavyweight rag paper with almost no acid content, so there has been practically no chemical reaction between plants and paper. She secured each plant to the paper with nearly invisible white cotton thread. Almost every specimen was carefully labeled with phylum, genus, and species.

Mollie retained her plant collection as a cherished keepsake. It stayed in her family and against all odds, was always well stored, away from extremes of temperature and humidity. In 1983 Mrs. J. R. Nelson, widow of one of Mollie’s descendants, presented the collection to Williston Northampton. Continue reading