There was a time, only a generation or two back, when private schools were expected to have a few Great Eccentrics on their faculties. In an era when people much more frequently kept the same job for a lifetime, and when residential faculty were discouraged from marrying, schools became, in a sense, havens for a few talented individuals who, for whatever reason, could not or would not easily thrive in outside society. Williston Seminary was no exception. Even so, for an unholy combination of inspired teaching and rampant misanthropy, one name stands out.

There was a time, only a generation or two back, when private schools were expected to have a few Great Eccentrics on their faculties. In an era when people much more frequently kept the same job for a lifetime, and when residential faculty were discouraged from marrying, schools became, in a sense, havens for a few talented individuals who, for whatever reason, could not or would not easily thrive in outside society. Williston Seminary was no exception. Even so, for an unholy combination of inspired teaching and rampant misanthropy, one name stands out.

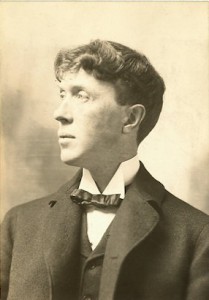

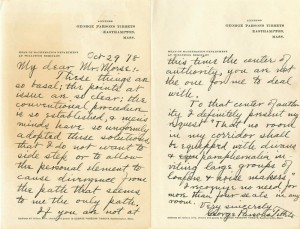

George Parsons Tibbets taught Mathematics at Williston Seminary from 1890-1926. Over six feet tall, “a great body topped with a strong face and crowned with a flaming thatch of red hair,” he was “a marked man in any crowd.” (Holyoke Transcript, April 7, 1926) And that was before one discovered that he had no talent for, or perhaps interest in, what most people considered normal social skills. Even his best friend and faculty colleague of 36 years, Sidney Nelson Morse, noted – in Tibbets’ eulogy, no less — that he was “at times insistently importunate, imperious, and impertinent.” “His attitude was a perpetual challenge to all whom he met.” Tibbets tended to get straight to the point with what he called the “basal virtues” of his argument: “Conversation with him was seldom a smooth and halcyon sea of conventional phrases – there were wrinkles in it, made by the fusillade of his pelting comments.” (S. N. Morse, Eulogy, corrected typescript and Williston Bulletin, November 1926.)

Perhaps Morse is describing a man whose mind was working so fast that his mouth couldn’t keep up within the bounds of “normal” etiquette. Another longtime colleague, Charles A. Buffum, recalled that beyond Tibbets’ area of unquestioned expertise, mathematics, there was the mind of a perpetual student, a polymath who, though “not a great reader, made himself familiar with the world’s best literature, the world’s best art and the world’s best music,” who took to reading philosophy for recreation, who had even taken medical school courses over several summers. “I could name a score of such subjects to which he devoted himself ardently and almost exclusively for a time, until he had mastered them . . . when he would dismiss them from his thoughts altogether and turn to some new problem. Some of these were intended merely for diversion, like banjo-playing, billiards, or bridge; others were more serious or strictly professional, like flash-light photography, stereopticon slides, music . . . artillery practice, bridge-building, and the automobile.” (C. A. Buffum, corrected typescript and Williston Bulletin, November 1926.) Whether or not he considered music a diversion, Tibbets, according to an obituary in an unidentified newspaper, was described by Buffum as “one of the best banjo players that could be found among either amateurs or professionals.”

It is difficult to contemplate Tibbets’ conversation at the bridge table. And he didn’t relish, or probably even understand, relationships with the rest of humanity. He typically purchased three theater tickets so that he wouldn’t have to sit with anyone. He attempted to have sofas and extra chairs removed from his dormitory to discourage loafers. But underlying the risible attributes of his persona, there was something terribly sad. Buffum wrote, “He chose to make the game of life a game of solitaire. [His friends] could not but realize that some of the sweetest and holiest relations of life he was missing altogether . . . though in his life there was no lack of motion, his emotions he did his best to hide. I believe he was in reality a man of deep feeling and genuine sympathy, but he seemed determined that nobody should find it out.” But as shall be seen, that wasn’t quite true. Tibbets’ students knew a different man.

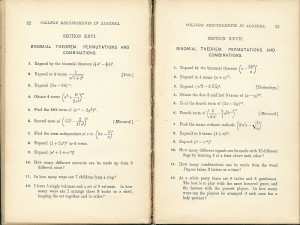

Tibbets was a unique, and uniquely demanding, math teacher who employed methods that would be considered innovative a century later. He didn’t like to lecture. Learning and teaching were meant to be collaborative. His students, having prepared – exhaustively, if they knew what was good for them – the night before, would take their stations at the blackboards surrounding the classroom. Each had a problem which he would attempt to explain, with encouragement and assistance from his fellows. Tibbets would guide, cajole, suggest . . . it was a voyage of mutual discovery.

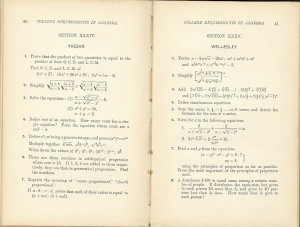

Indeed, according to Robert Wood, class of 1900, Tibbets loved the opportunity to draw further discussion from the class: “I can answer that, but I can’t answer it now.” While surviving teaching materials confirm that he expected accurate answers, they really weren’t the point at all. He would declare to his classes, “Algebra? Nothing. Geometry? Nothing. The problem? Everything!” (Unnamed alumnus, Williston Bulletin, November 1926.) Years later, alumni recalled what it was worth. Among many dozens of encomiums, that of Ward Van B. Hart, class of 1910, is typical: “As one who first learned from you the spirit of mathematics as opposed to mere technical adroitness in manipulation of figures . . .” (Hart, letter to Tibbets, 1926)

Tibbets could be hilariously scathing toward anyone he suspected wasn’t keeping up. Wood writes, “‘Now, Gentlemen’ . . . : At those two words the blood seemed to congeal in my veins . . . When he started off like that and some hapless fellow was standing, I knew it was possibly the signal for the class to hear what the professor thought of that man’s effort or lack of it. No, he would not say outright that so-and-so was deficient . . . he used more finesse than that.” But Wood soon learned that terror was only incidental to Tibbets’ agenda. “Never again did I suffer stage fright in class or in examination, thanks to the humanity of that wonderful man, from whose courses I derived the utmost pleasure, satisfaction, and profit. I almost adored the ground upon which he trod.” (Robert F. Wood, Recollections of Williston in the Eighteen-Nineties,Typescript, 1956)

Adored? Humanity? Is this the same person? Yet the files are full of similar recollections from alumni. At a time when most faculty were rarely seen or heard in their students’ lives outside of class, Williston students flocked to Tibbets for advice. He was an extraordinary listener. They knew they could count on him for honesty – perhaps too much of it. And he had a special talent for clearing away irrelevancy and getting straight to the point. One might wonder what advice a man who apparently didn’t comprehend the art of living might give. But Tibbets had a youthful past he could draw from, one barely known to his adult colleagues. Charles Buffum wrote that in 1889, when Tibbets interviewed for his eventual position at Williston, he gave as his references “The Professors of Amherst College, provided you ask about nothing previous to the end of Sophomore year.” It eventually became known that Amherst Professor Richard H. Mather, later a member of the Williston Board of Trustees, had taken a “careless and pleasure-loving boy” under his wing and set him on a different path. Tibbets, shepherding his students, was doing no more than paying his debt to Mather.

Indeed, wrote Morse, Tibbets’ was “a name to conjure with. In a company of Williston [alumni], no other name could so instantaneously wake the mirth and enthusiasm of the crowd as that of Professor Tibbets – a man who has left the impress of his character upon thousands of boys – a teacher whose far reaching influence can never be measured.” And Robert Wood recalled that while a student at Williams College, he was told by the head of the mathematics department that he could always spot a Tibbets protégé in his classes by his “fundamental conception of the meaning of accuracy and meticulous care.”

Tibbets would have liked that. Frequently recruited by college faculties that could offer better pay and prestige, he was adamant. “My mission in life is to teach the younger boys.” (Wood)

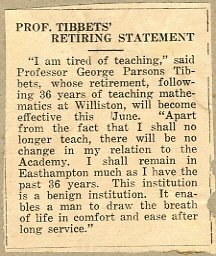

In April of 1926 Tibbets suddenly retired, effective at the close of the school year. He told the Holyoke Transcript that he was “tired of teaching.” There was a suggestion that a faction on the Board had engineered his departure. Neither was remotely true. The reality was that he’d been in failing health for several years – possibly heart trouble. Typically, wishing neither sympathy nor intrusive attention, he hadn’t told anyone. A bout with influenza had weakened him. To give the impression that he was returning, he left his possessions in his Easthampton apartment and gave Headmaster Archibald Galbraith an envelope containing his financial records, will, and instructions for paying the bills. He entered a sanitarium in Lynn, Mass., and died on June 20, aged 62.

In April of 1926 Tibbets suddenly retired, effective at the close of the school year. He told the Holyoke Transcript that he was “tired of teaching.” There was a suggestion that a faction on the Board had engineered his departure. Neither was remotely true. The reality was that he’d been in failing health for several years – possibly heart trouble. Typically, wishing neither sympathy nor intrusive attention, he hadn’t told anyone. A bout with influenza had weakened him. To give the impression that he was returning, he left his possessions in his Easthampton apartment and gave Headmaster Archibald Galbraith an envelope containing his financial records, will, and instructions for paying the bills. He entered a sanitarium in Lynn, Mass., and died on June 20, aged 62.

Who among your teachers was especially memorable? Please click to take our survey!

Your comments and questions are welcome! Please use the form below.

I think I like your Professor Tibbets. I imagine that in this day and age he would have spent half his time with psychologists. Do you think he was autistic?

An interesting question. Asperger’s Syndrome, which has only recently been identified as a condition separate from Autism, has also been suggested. But I am not qualified to make a diagnosis. I will note that my understanding of both syndromes is that they usually manifest themselves in young people. George Tibbets joined the faculty aged 26, having previously served in public schools as Principal (then considered a young man’s job) and math instructor for the previous five years. The antics of a beloved middle-aged eccentric savant were unlikely to have been tolerated in a young man at the outset of his career, particularly in an age that had never heard of Autism and that routinely incarcerated the “mad.” This suggests that Tibbets acquired, or at least ceased to suppress, his idiosyncracies only as he aged.

In part through Tibbets’ own preference, we know almost nothing of his life before Williston. After graduating Amherst in 1885, he held five different principal’s jobs in as many years. Does this suggest that something wasn’t quite right? Perhaps. But he was never without school employment. Williston hired him as Head of the Math Department – not something Principal William Gallagher, a cautious man, is likely to have done had there been any question of Tibbets’ “suitability.”

From the description of him in this wonderful blog, I don’t think he was severely autistic. As Rick Teller suggests, however, he might be diagnosed, nowadays, as having Asperger’s syndrome. It certainly sounds like he was a brilliant person who had some social skills deficits similar to those seen in people with Asperger’s. I wish I had had a chance to meet him in person.