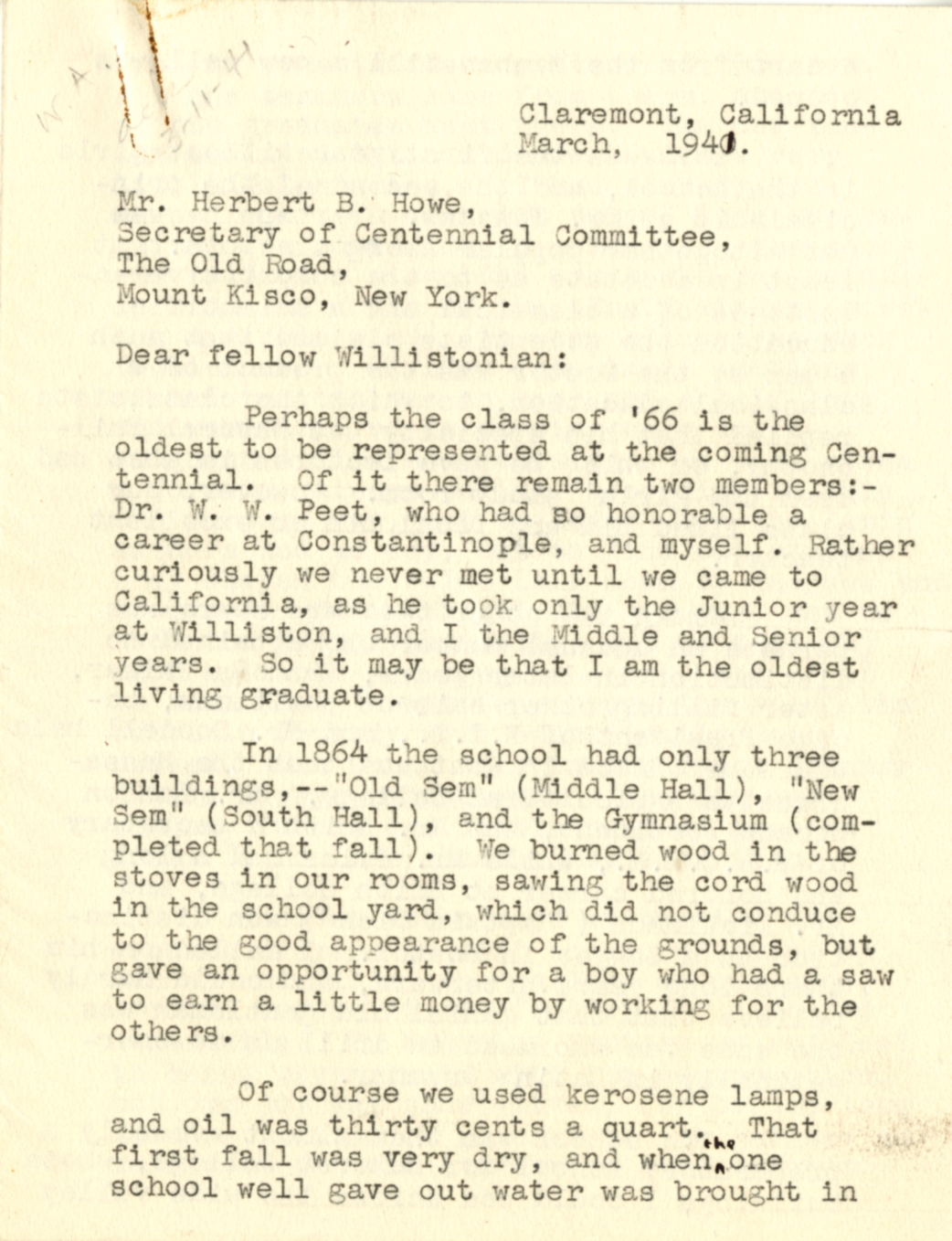

Dwight Whitney Learned (1848-1943), a native of Canturbury, Connecticut, graduated Williston Seminary in 1866 and Yale, B.A. 1870, Ph.D. 1873. He was a grand-nephew of Samuel Williston, his grandmother having been Samuel’s sister Sarah; that may have explained his choice of Williston to prepare for college. Following Yale, he taught Greek and mathematics at Thayer College in Kidder, Missouri, for two years, where he was ordained in the Congregational ministry. In 1875, under the banner of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, he went to Japan, where for 53 years he was professor of church history and theology at Doshisha University in Kyoto. He published extensively in both Japanese and English, and contributed to a Japanese translation of the New Testament. Upon his retirement in 1928, he was honored by the Emperor. He settled in Claremont, California, where he continued to preach and write.

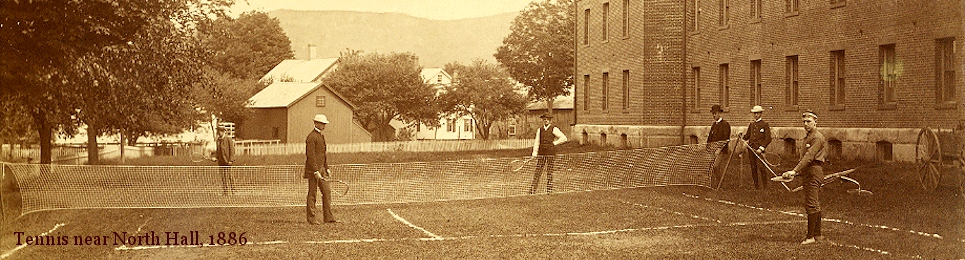

In 1941, as the centennial of Williston’s founding approached, Learned sent a typed memoir to centennial organizer Herbert B. Howe, class of 1905. As he points out, aged 92, he must have been among the oldest living alumni. Learned’s pages are reproduced here, with only a few annotations. They are an interesting window into student life during and after the Civil War, and even touch on the Confederate surrender and Lincoln’s assassination. It must also be noted that Learned’s recollections of Williston academic life, while amusing, are not altogether complimentary. (To enlarge any image, please click on it.)

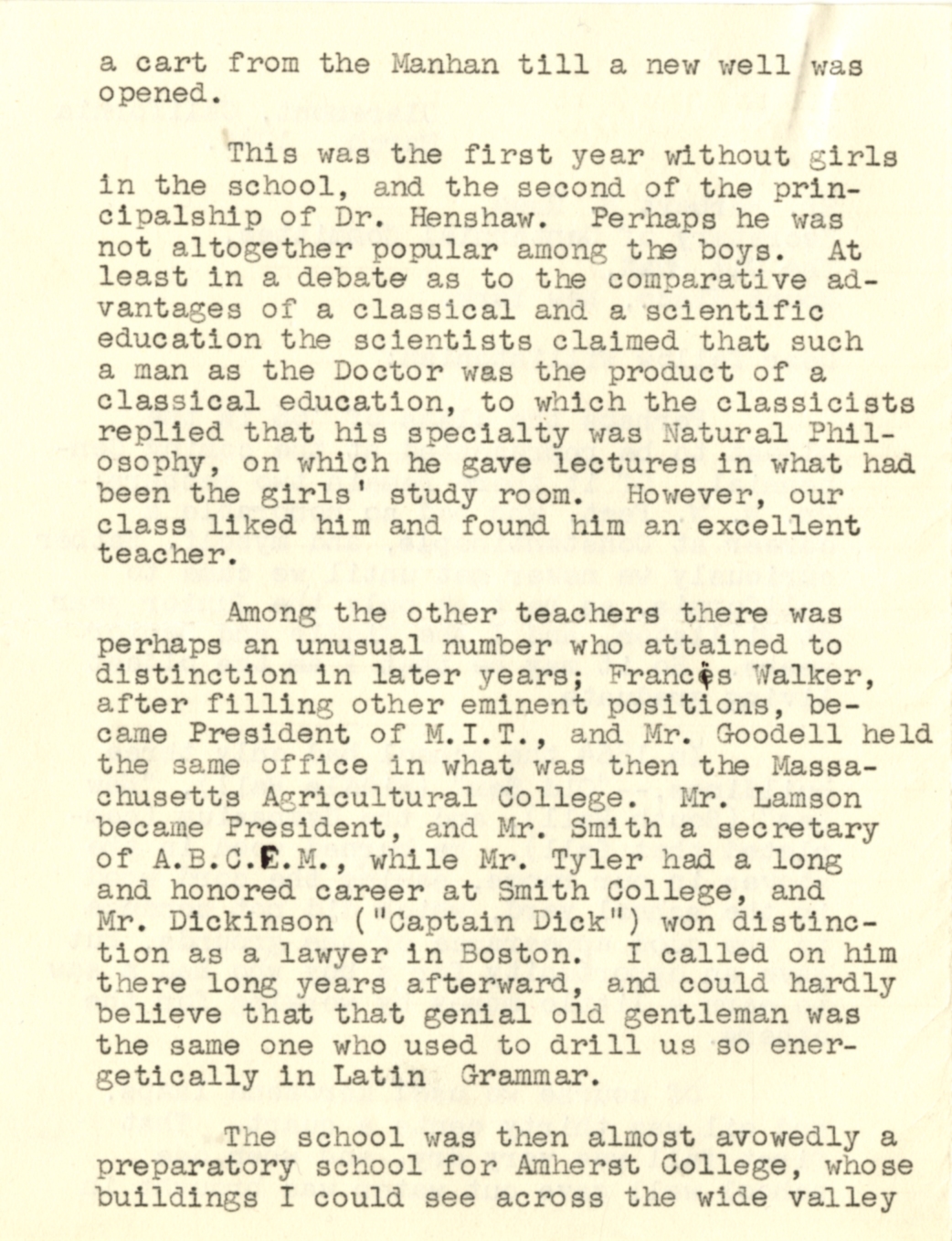

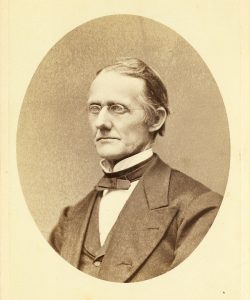

Marshall Henshaw served as Principal from 1863-1876. Both respected and feared by his students, of him Joseph Sawyer once wrote that “a botched translation was highway murder.” Williston Seminary had been coeducational until 1864, when Samuel Williston constructed a new public high school for Easthampton. The faculty mentioned by Learned, Amherst graduates all, were young men when they taught at Williston: Francis A. Walker became an eminent economist; Henry Goodell ’58 the founding President of Massachusetts Agricultural College; Charles M. Lamson ’60 and Thomas Smith important figures on the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions. Classicist Henry Mather Tyler ’61 taught at Knox and Smith Colleges, and wrote an important history of the latter; while Marquis F. Dickinson ’58 became a distinguished attorney and, coincidentally, Samuel Williston’s son-in-law.

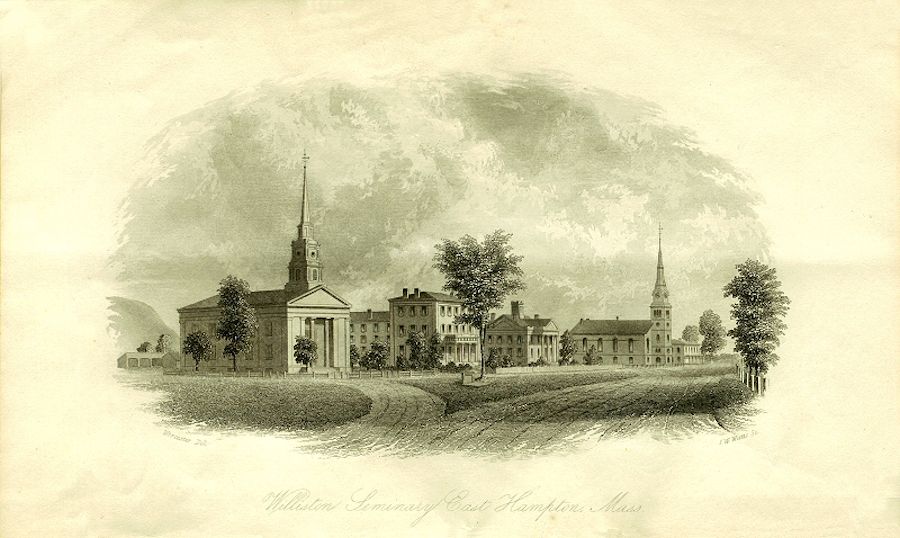

It is surprising to learn that in days of cleaner air and lower buildings, one could see Amherst college, eleven miles distant, from an upper story in Easthampton. Williston students attended services at the Payson Church, next to the campus.

It is surprising to learn that in days of cleaner air and lower buildings, one could see Amherst college, eleven miles distant, from an upper story in Easthampton. Williston students attended services at the Payson Church, next to the campus.

Adelphi was the Seminary’s debating and literary society. Its rival, Gamma Sigma, had not yet been founded.

Adelphi was the Seminary’s debating and literary society. Its rival, Gamma Sigma, had not yet been founded.

If, presumably, Learned is evoking the Confederate surrender at Appomattox, then he has misremembered the date, April 9, 1865 – although General Grant had indeed written Robert E. Lee on the seventh, offering to discuss terms of surrender.

If, presumably, Learned is evoking the Confederate surrender at Appomattox, then he has misremembered the date, April 9, 1865 – although General Grant had indeed written Robert E. Lee on the seventh, offering to discuss terms of surrender.

Happy New Year from the Williston Northampton Archives!