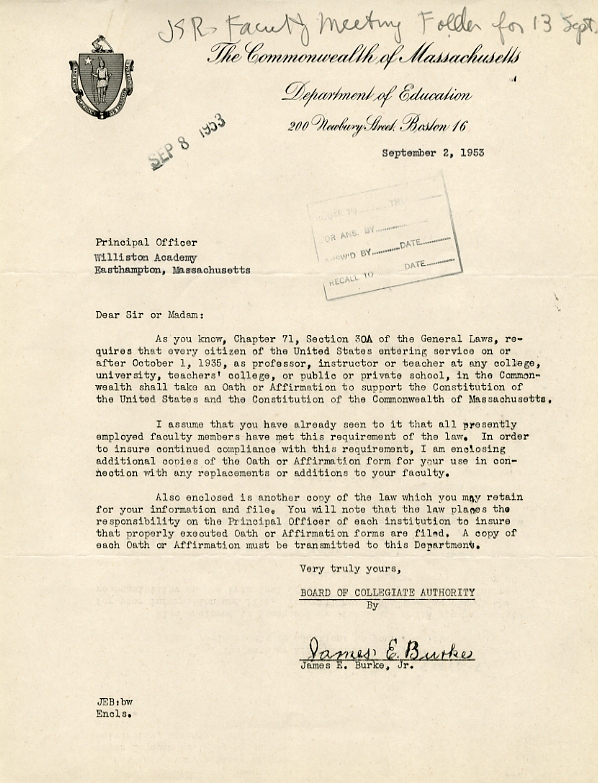

As the summer of 1953 was ending, the United States was extricating itself from the Korean War. An armistice agreement had been signed at Panmumjom on July 27, ending active hostilities on the Peninsula but doing nothing to abate the Cold War nor to dampen anti-communist fervor at home. Indeed, what is now remembered as the Second Red Scare (1947-1954) continued to dominate the political news. But in quiet little Easthampton it was, perhaps, relatively easy to ignore the issue as a phenomenon centered in Washington, Hollywood, and New York. Then, just as school was about to begin, Headmaster Phillips Stevens received the following letter:

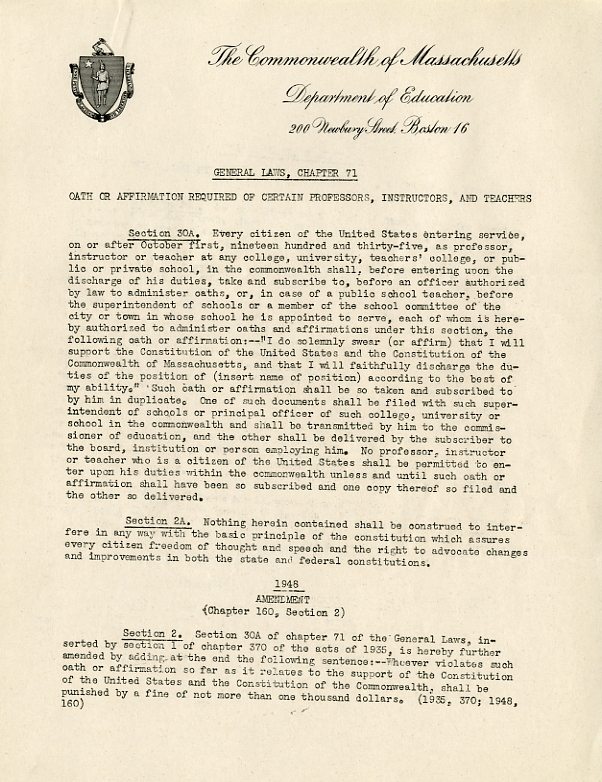

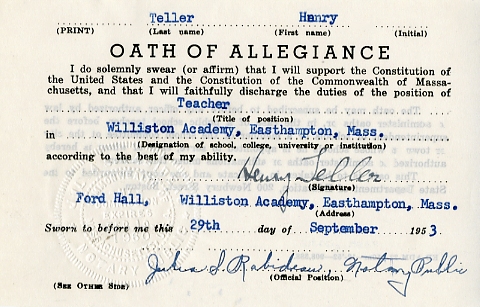

It was accompanied by this document:

Note that the law had been enacted in 1935. But there is nothing in the Archives to suggest that in the 18 years prior to 1953, anyone on the faculty had been asked to affirm his loyalty in any way. Suddenly a state governmental board was asserting itself, notably in language — see the second and third paragraphs of James E. Burke’s letter — that could be construed as coercive. Burke provided a stack of blank forms, which were duly, and quickly, distributed to the faculty.

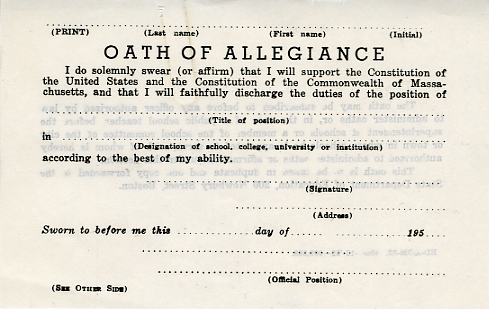

Here is where the story becomes personal. This writer’s father, a man whom I remember as valuing strong and honest opinion, who mistrusted, if not despised, intellectual coercion of any kind, nonetheless signed the oath.

Here is where the story becomes personal. This writer’s father, a man whom I remember as valuing strong and honest opinion, who mistrusted, if not despised, intellectual coercion of any kind, nonetheless signed the oath.

Twelve of twenty-six faculty did not sign. Seven of those listed had been hired prior to 1935 and were thus exempt, but five — Dale Lash, William Lauman, James Shepardson, David Stevens, and Leon Waskiewicz ’42, for reasons not documented, were not. There is no indication that there was ever any follow-up to this, either internally or from any outside agency. Indeed, by the following June Senator Joseph McCarthy, the de facto leader of the Congressional anticommunist crusade, had been publicly discredited, and the Great Red Scare largely collapsed under the weight of its own paranoia. Faculty were never again required to assert their political loyalty.

Massachusetts General Laws, Chapter 71, Section 30A was not repealed until 1986.

Chilling.

I am amazed at the names I see there of those who refused (or rather abstained) to sign. Today, where I live near Cleveland, there seem to be so few who have the intellectual curiosity and/or historical perspective to be aware of the consequences of either signing or not signing. We already live in very different times. Thank you Rick for an astounding retrospective.