We are not a campus of monuments. Other schools may have their statues of alumni Presidents, of creepy idealized schoolboys, of King Ozymandias . . . Williston has a statue called “The Actor,” generally understood to represent a fictional knight whose every attribute defies institutional aspirations toward Purpose, Passion, and Integrity. And, of course, a lion. No . . . The Lion.

We are not a campus of monuments. Other schools may have their statues of alumni Presidents, of creepy idealized schoolboys, of King Ozymandias . . . Williston has a statue called “The Actor,” generally understood to represent a fictional knight whose every attribute defies institutional aspirations toward Purpose, Passion, and Integrity. And, of course, a lion. No . . . The Lion.

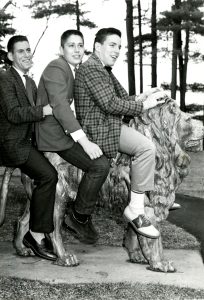

The Lion has no name, nor does he represent the school’s Wildcat mascot. He stands guarding the flagpole. His empty eyes scan Mount Tom, perhaps anticipating danger from the bike path. For generations he has been a magnet for children, some of them quite old, who cannot resist riding him. Chameleonlike, his colors change so often that while his aging body is cast iron, observers may be forgiven for assuming that he is comprised entirely of layers of paint. Perhaps like Auden’s Sphinx, The Lion is admired, but unloved.

The Lion has no name, nor does he represent the school’s Wildcat mascot. He stands guarding the flagpole. His empty eyes scan Mount Tom, perhaps anticipating danger from the bike path. For generations he has been a magnet for children, some of them quite old, who cannot resist riding him. Chameleonlike, his colors change so often that while his aging body is cast iron, observers may be forgiven for assuming that he is comprised entirely of layers of paint. Perhaps like Auden’s Sphinx, The Lion is admired, but unloved.

Periodically, especially before important events like Convocation and Commencement, The Lion metamorphoses to a neutral color, institutionally repainted in the name of Looking Neat and Clean. It never lasts. The Lion has celebrated the national holidays of many countries, graduations, and the occasional birthday. At times of local or national tragedy, leonine memorials have been de rigeur. These have tended to last longer than other redecorative efforts. He has been painted to advertise school plays, has appeared in support of political candidates, has been colored pink to promote breast cancer awareness, and adopted a rainbow insignia to commemorate Williston’s participation in an LGBDQ Day of Silence.

Not every paint job has been so high-minded. A couple of years ago, The Lion sported an odd shade of light blue, serving as background for a too-public senior prom invitation. (Embarrassed, she declined.) And painting traditions have changed over the years. There was a time when a student subject to involuntary early departure might leave a farewell message. More often, his friends would paint the beast in the miscreant’s memory. Until a recent shift in tradition, it was rare actually to see anyone painting The Lion. Most of the time, he appeared, overnight, to have painted himself.

How the Lion Came to Williston

The Lion was brought to Easthampton in the 1920s by Williston Junior School Headmaster Edward Clare (for whom Clare House is named), and was installed next to what is now called Swan Cottage, on the crest of the Main Street Precipice. When Ed Clare died suddenly in 1947, his widow Hazel stayed on, as did his Lion. In 1965 the statue was relocated to a spot on the main campus, next to the Theater, where it remained until 1996, at which time it was moved to its present location, to make room for Falstaff.

The Legend of the Lion

According to legend, as transmitted by Hazel Clare, The Lion was one of a pair that stood overlooking the Charles River in Boston, on the property of a British merchant. At the time of the Boston Tea Party, a mob invaded the merchant’s house and dumped the lions into the river. The Tory fled to Canada, and the lions remained underwater until around the time of the Civil War, when they were dredged from the river during the expansion of the Charlestown Navy Yard. Col. George Moore was the officer in charge of the recovery operation. In civilian life, Col. Moore sold pianos. That detail becomes relevant because at home in nearby Walpole, Mass., Moore had access to a variety of cranes, blocks, and tackles meant for hoisting pianos through upper-story windows, thus also useful for fishing cast iron lions out of the muck. Moore took one of the lions for himself and installed it at his Walpole residence, which he named Lionhurst. The second lion was taken by someone else, and lost to history. Col. Moore had a daughter, Treby Moore. Treby, who never married, was Edward Clare’s aunt. She gave Ed the Lion, which he brought to Easthampton. Continue reading