From the Archivist’s Bookshelf

In the half-century prior to the Civil War, antislavery sentiment was strong up and down the Connecticut Valley. Yet there was an essential conflict between two schools of Abolitionists: the high-minded movement inspired by reformer and The Liberator editor William Lloyd Garrison (1805-1879), and a number of rabble-rousers who advocated more direct action.

In the half-century prior to the Civil War, antislavery sentiment was strong up and down the Connecticut Valley. Yet there was an essential conflict between two schools of Abolitionists: the high-minded movement inspired by reformer and The Liberator editor William Lloyd Garrison (1805-1879), and a number of rabble-rousers who advocated more direct action.

Five of the latter, all residing in Northampton, are treated in a new book by Bruce Laurie, Rebels in Paradise: Sketches of Northampton Abolitionists (Amherst: The University of Massachusetts Press, 2015). Dr. Laurie (Professor Emeritus of History, UMass Amherst) has selected the scholarly Sylvester Judd, African-American Underground Railroad conductor David Ruggles, newspaper editor Henry S. Gere, and preacher-turned-entrepreneur Erastus Hopkins. Not least among them was Samuel Williston’s brother, manufacturer John Payson Williston. All were local business, religious, and political leaders; none was especially subtle in advocacy of favorite causes, be they temperance, political reform, or the abolition of slavery.

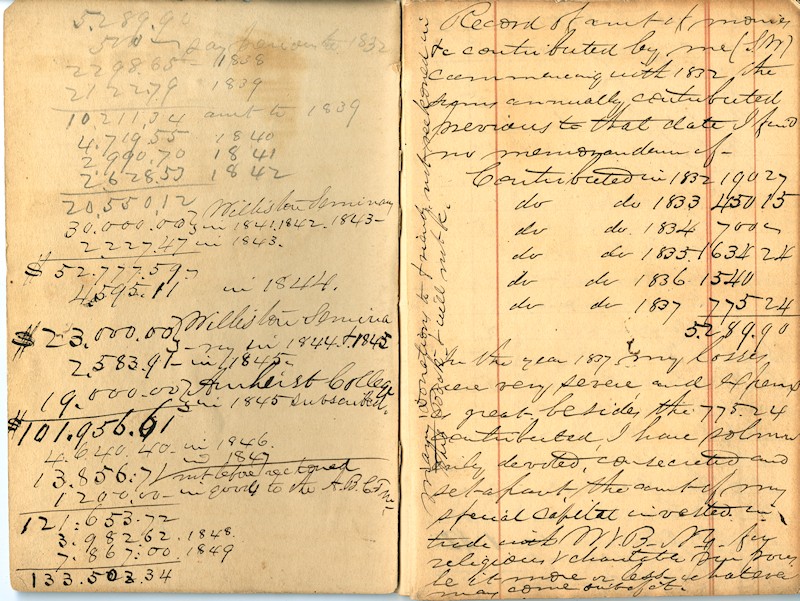

Like his elder brother Samuel, John Payson Williston (1803-1872) broke with several generations of Williston male tradition by choosing a manufacturing career over the Congregational ministry. Again similar to Samuel’s experience, the decision was driven by circumstance: neither was able to complete a university education because of poor eyesight. From there, their paths diverged. Samuel, largely through prescient investment, became one of Western Massachusetts’ leading industrial barons and philanthropists, but one whose public advocacy of reformist concerns, however passionately he believed in them, was often held in check by a need to protect his Southern business interests and, perhaps, the desire to project a certain patrician reticence. Continue reading