The Archives Acquire a Fascinating Record of Science Teaching

It was one of those phone calls that vastly improves one’s week. “My name is Will Wyatt – I’m a dentist in Texas. I have what appear to be a notebook from a Williston biology class, dated 1890. Would you like it for the Archives? If so, I’d be happy to donate it.”

Would I like it? That would have been an understatement. Among the more important things we collect are examples of academic work: what was studied, and how it was taught, going back to our beginnings 175 years ago. We actively seek current student work, as well as that from the past. Consider: all the other things we save and cherish – theater photos, box scores, school newspapers, and dozens of other categories, most of them well-represented in this blog, wouldn’t even exist without the academic program. It provides a context for everything else in our daily lives at a busy school. Academics are the most important thing we do at Williston.

So yes, we were thrilled to accept Dr. Wyatt’s generosity – the more so given the age of the item. It is relatively easy to lay hands on student papers from 2015. Anything from the 19th century is another story entirely. And as shall be seen, this particular item is very special.

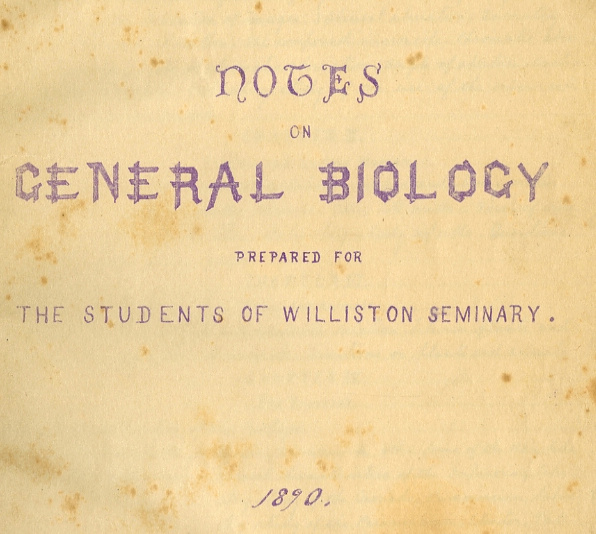

The document is a set of teaching notes for an 1890 Williston Seminary biology course taught by William Tyler Mather (1864-1937). Mather, Williston class of 1882, went on to Amherst College, graduating in 1886. He taught at Leicester Academy, 1886-1887 then, like many Williston and Amherst alumni, returned to Williston to teach (1887-1893). During this time he also completed a master’s degree at Amherst (1891). In 1894 he entered Johns Hopkins University, earning a Ph.D. in physics in 1897. In 1898 he became Professor of Physics at the University of Texas, Austin, where he remained the rest of his life. (This would tend to partially explain how a set of teaching notes found their way from Easthampton to “a very eclectic used book store” in San Antonio, where Will Wyatt purchased them in the 1980s.)

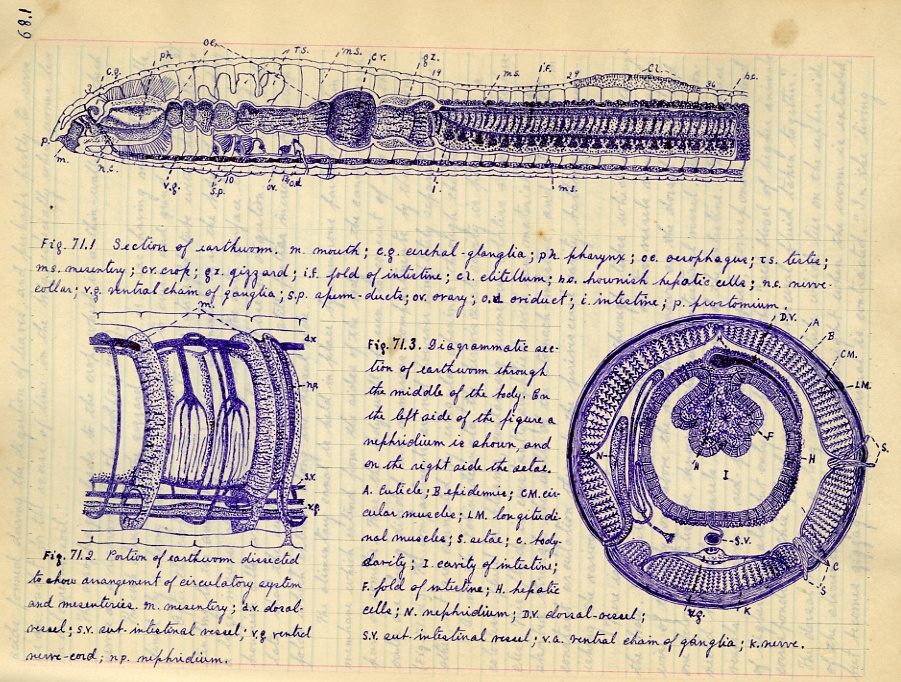

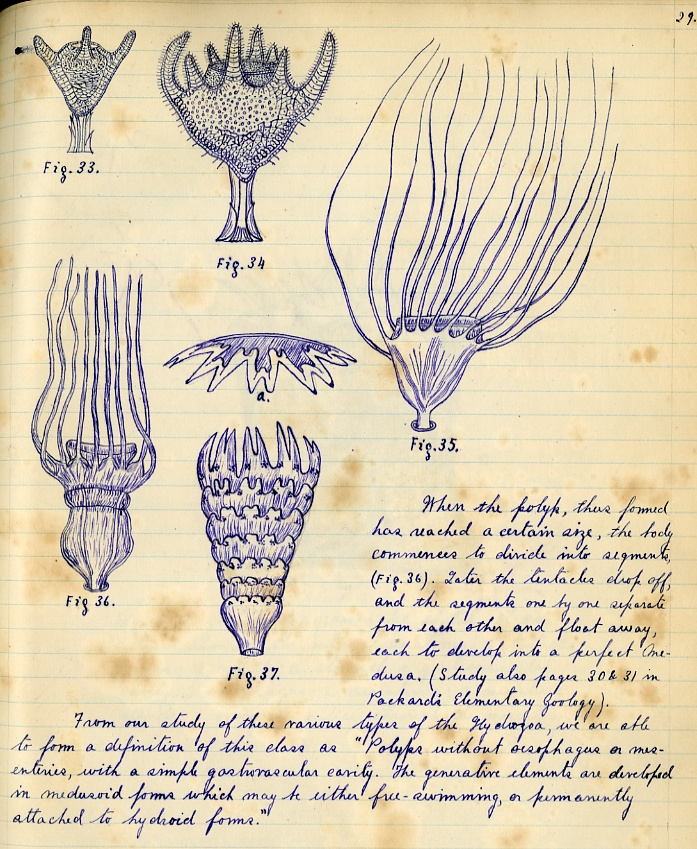

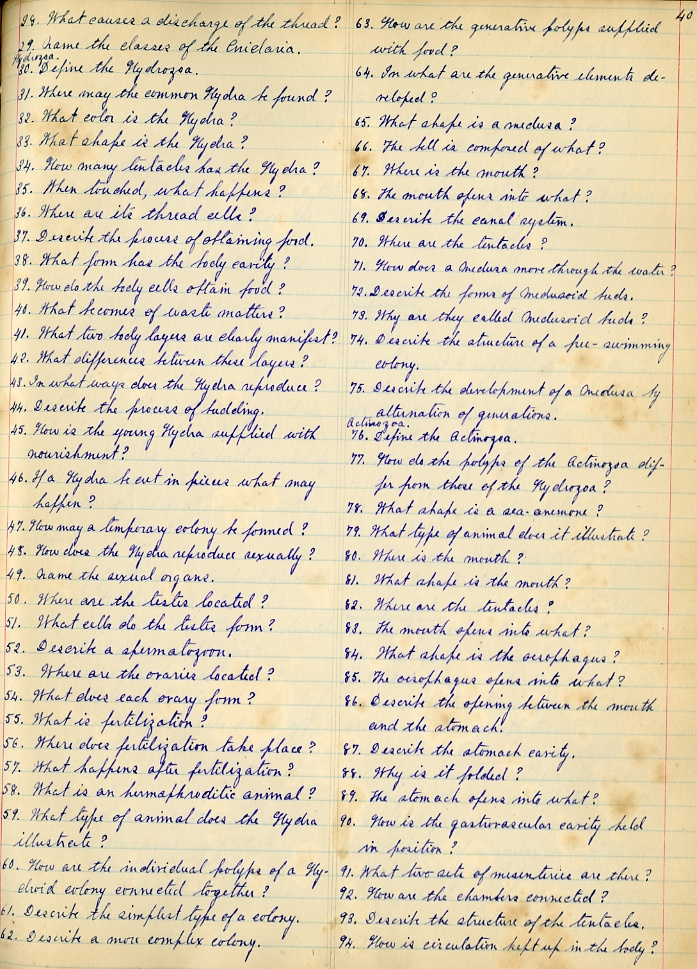

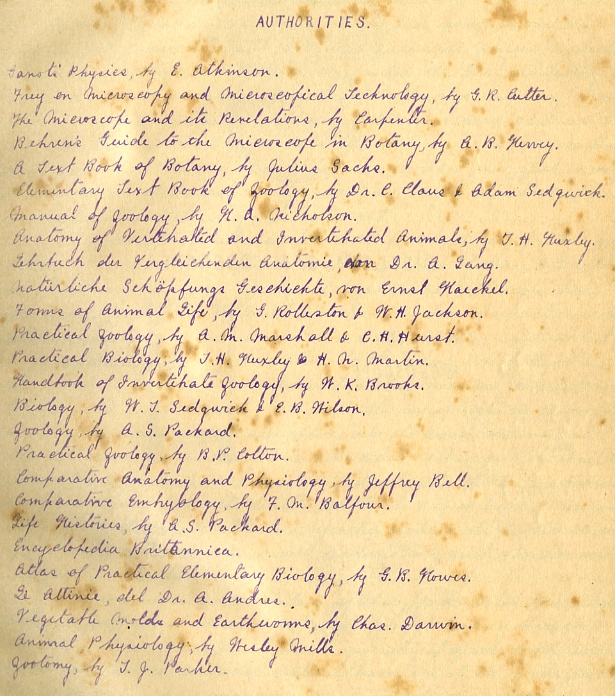

The notebook comprises 97 handwritten pages, in a leather binding. While entitled “Notes on General Biology,” the contents might more accurately be described as a survey of lower-order botany and invertebrate zoology. Since the text ends in the middle of a sentence on page 97, it seems likely that there was more, but whether only a few pages, or another volume, is unknown. A few of the pages are reproduced on some kind of spirit duplicating machine (see the caption to the title page, above). One may speculate that these were part of a version of the notes distributed to the class. The volume at hand is clearly Mather’s instructional notebook. It includes many pages simply listing questions — not merely potential test questions, but an outline by which a conscientious teacher could insure that he covered every point.

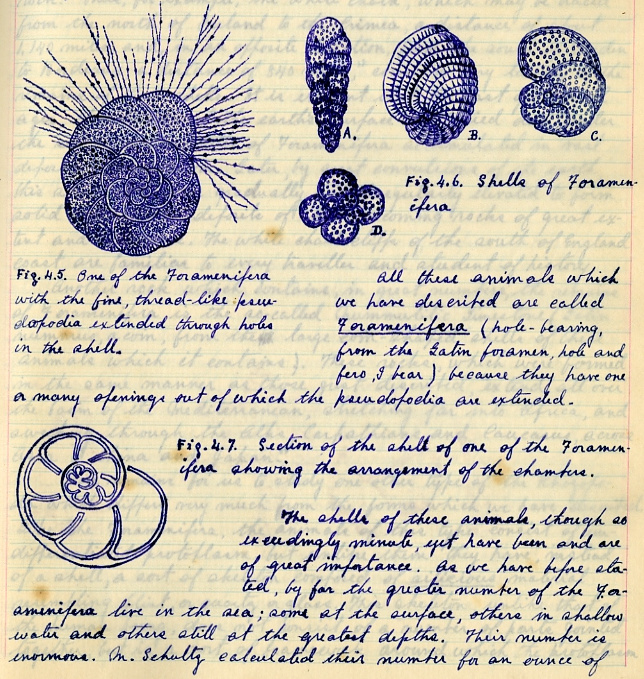

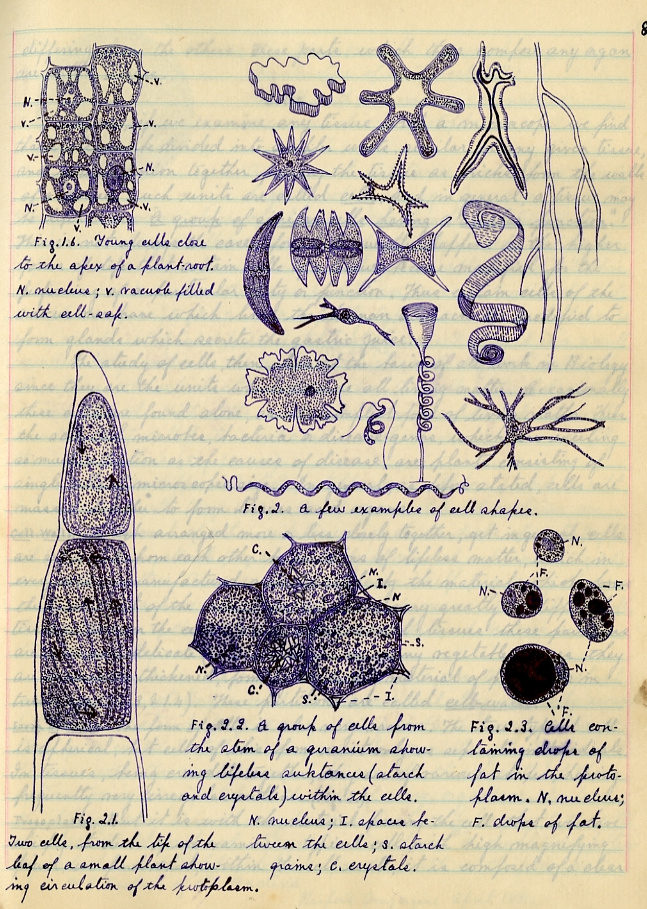

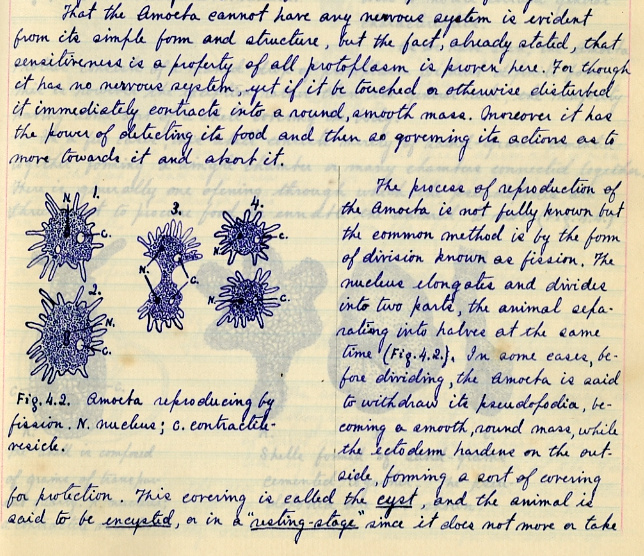

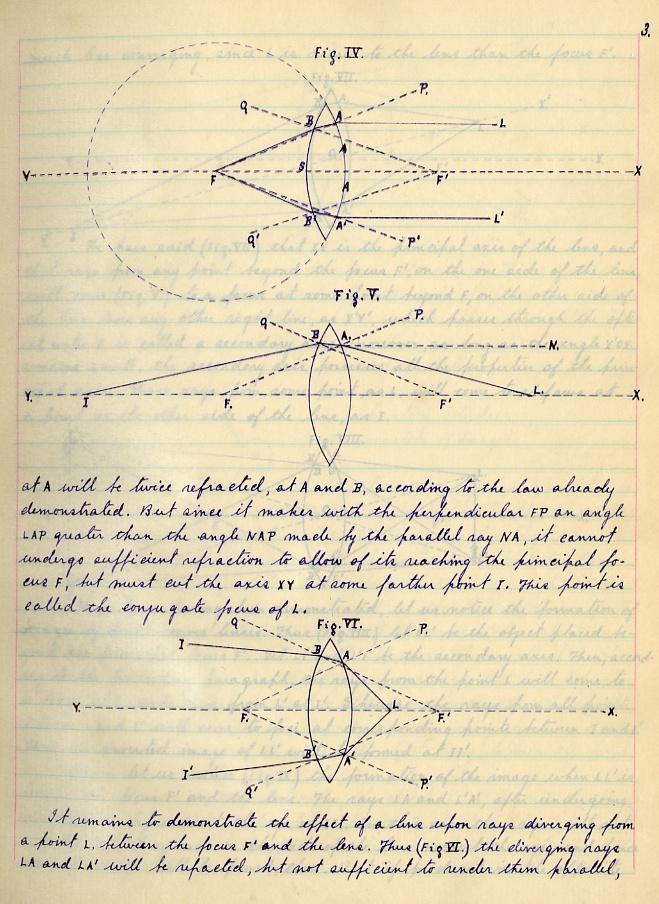

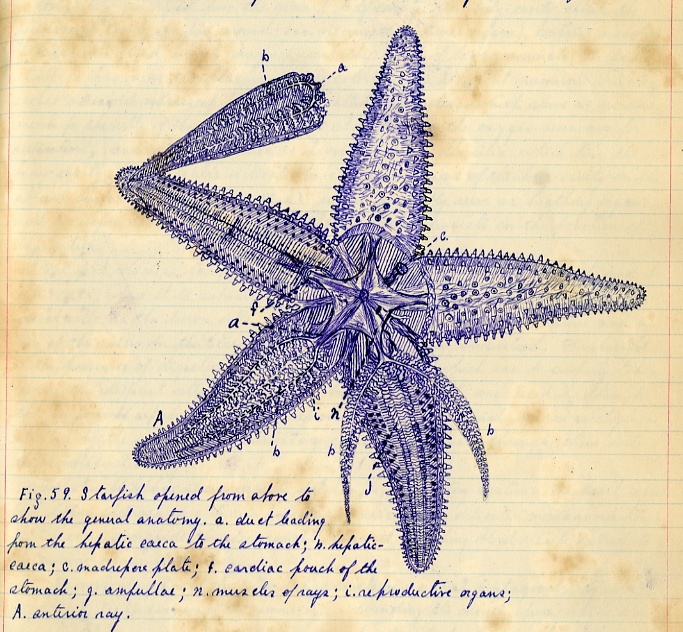

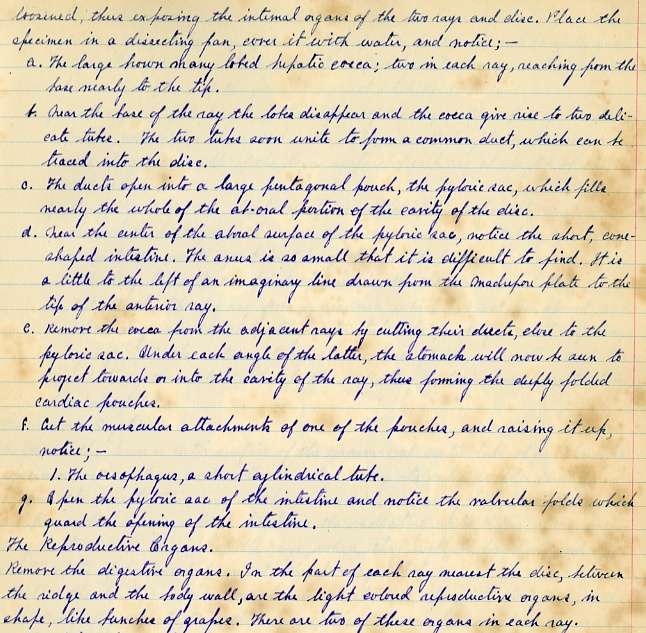

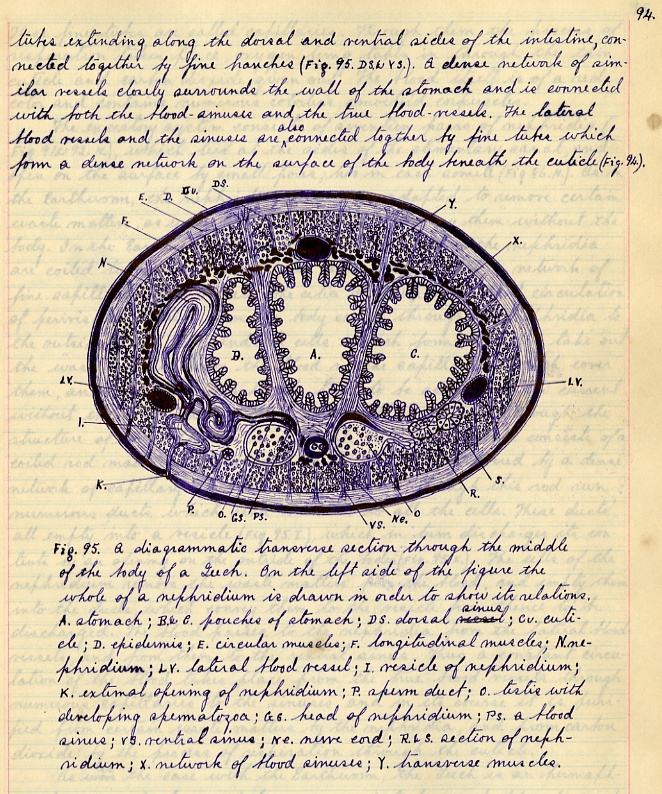

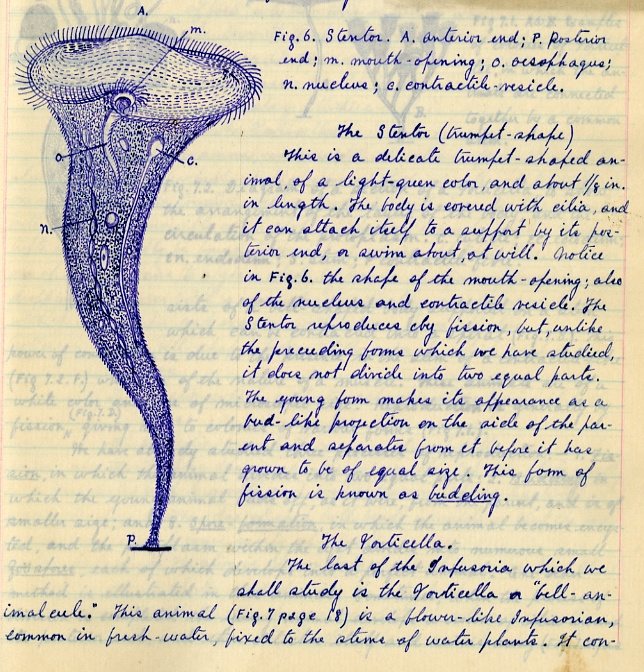

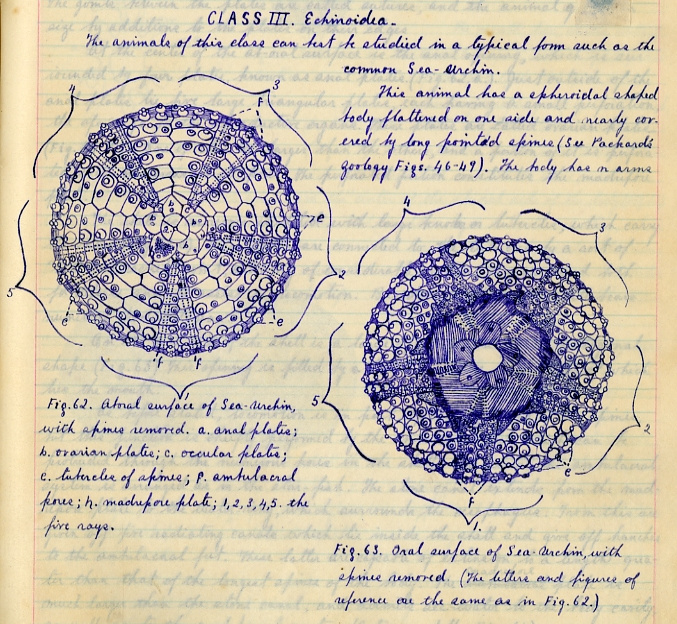

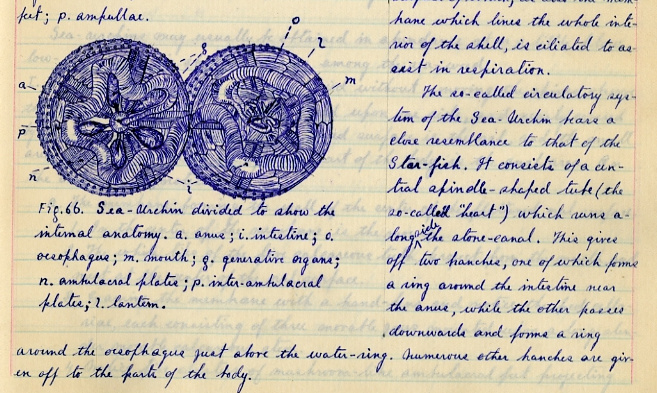

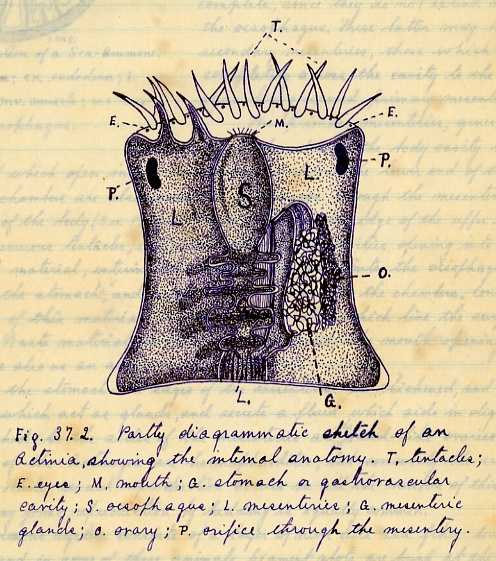

The best parts of the notebook are, of course, Mather’s drawings: meticulous, detailed, often employing several shades of blue and black ink. They are a reminder of a time when many scholars, especially naturalists, took special pride in accurately rendering what they described.

When told of the Archives acquisition of the Mather notebook, Williston biology teacher and Associate Head of School Jeff Ketcham commented that he would be “most interested to learn what is left out.” For example, “Darwin’s On the Origin of Species appeared in 1859, but I wouldn’t be surprised if it isn’t mentioned at all.” The point is well taken. It took time for innovative, never mind controversial, ideas to catch on, especially in an essentially conservative educational establishment. Mather’s bibliography of “Authorities” lists another work by Charles Darwin, but not his most significant one.

Mather introduces the term “paleontology,” and includes a chapter on fossils, which he describes as “any evidence of the former existence of a living thing,” while presenting petrification as only one of several processes of fossilization. He discusses extinction, noting that fossils are often records of earlier forms of modern animals, but does not attempt to present any process of evolution or natural selection. Similarly, in a course that emphasized microscopy, there was a focus on cells. They were presented primarily as an element of plant structure and of simple zoological organisms like amoebas. DNA was, of course, unknown at this time; but Gregor Mendel’s pioneering work in genetics had been published in 1866, with no effect on Mather’s syllabus.

Typically for the time, Mather’s approach to biology was based almost entirely on observation and description. There is no discussion of biochemical processes — indeed, much of what our present-day biology students may take for granted had not yet been discovered. Examination of organisms in their environmental or ecological contexts is largely absent here. But Mather demanded meticulous observational skills from his students, emphasizing dissection and the use of the microscope. And although biology was the subject at hand, Mather clearly expected his students to understand the principles of optics. Perhaps it is no surprise that he eventually became a physicist.

We invite you to enjoy additional pages from this wonderful document.

So glad to have been a part of getting this historical document to its rightful place.

Me too . . . thanks, Will!