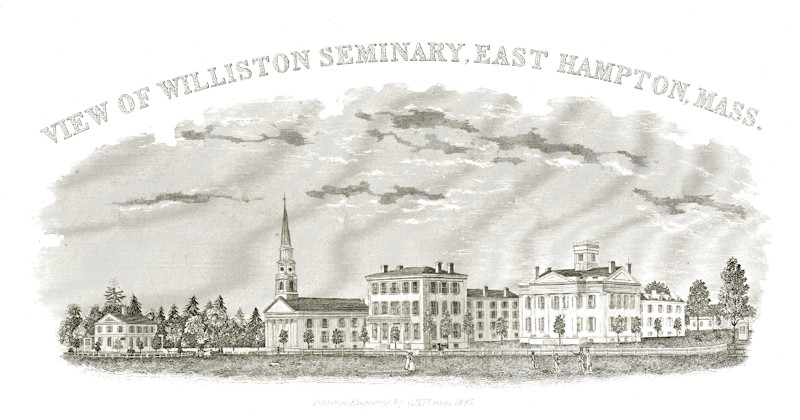

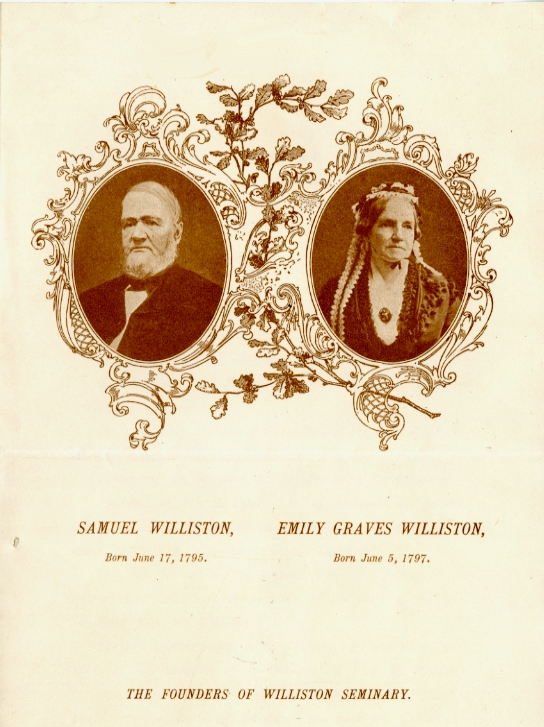

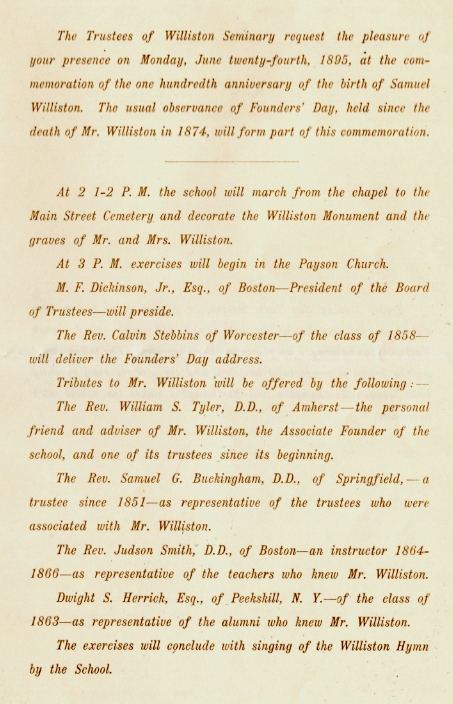

According to most evidence, Williston Seminary began to celebrate Founders’ Day shortly after Samuel Williston’s death in 1874. The original tradition was to commemorate the Founder on or close to his birthday, June 17. Typically it was one element of Senior Week, which culminated with graduation exercises. It was a major event. The oldest surviving program, from 1895, presents a full afternoon of wreath-laying and speeches.

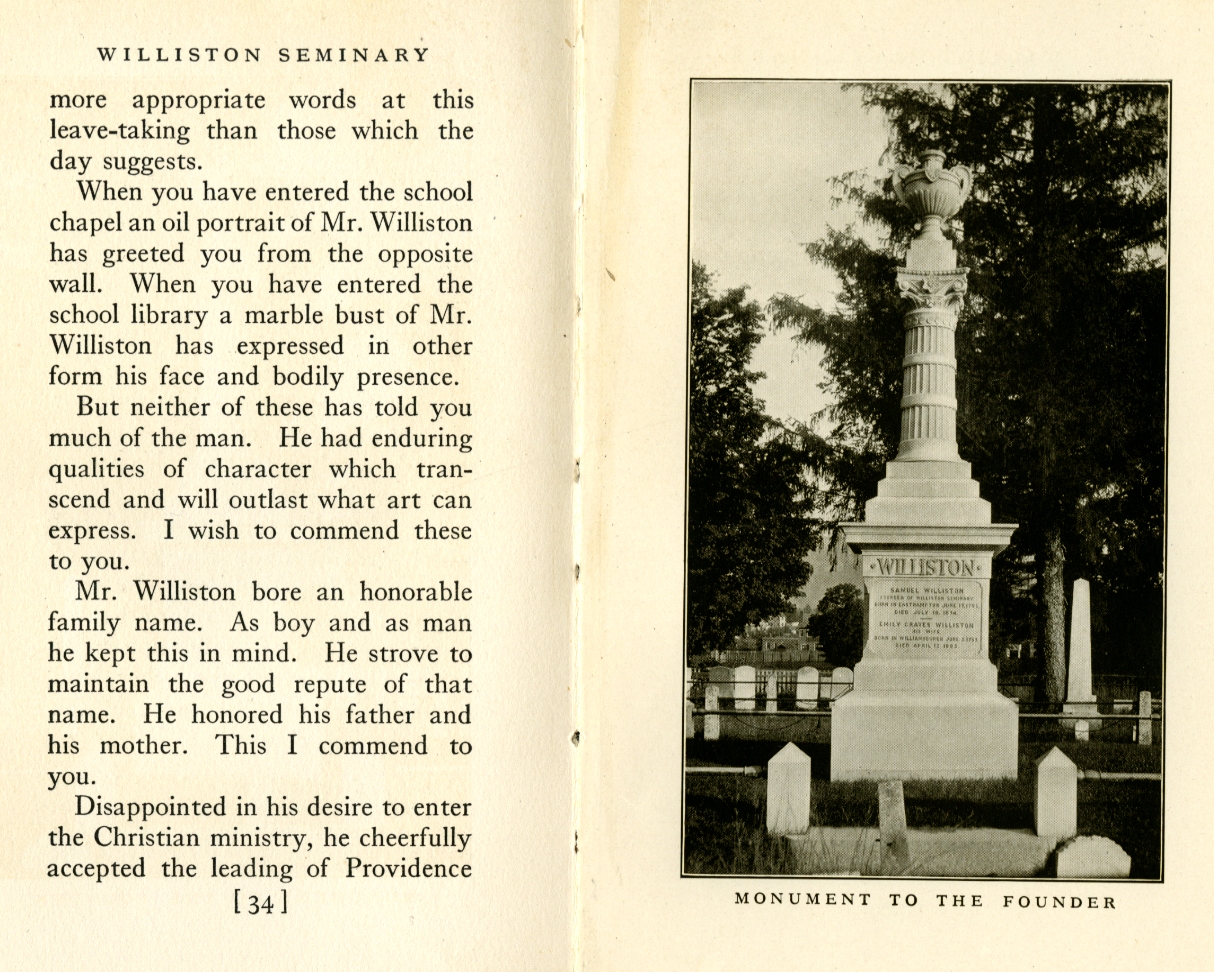

Some form of the event survived into the 1970s. By mid-century, it had been moved to a date earlier in the spring. The school assembled at the Williston gravesite in the Main Street Cemetery, where either the Headmaster or Dean A. L. Hepworth would talk about the Willistons, and typically many of the other former heads and faculty interred nearby.

In 2016, during Williston Northampton’s 175th Anniversary celebration, Founders’ Day was revived, now as a February event celebrating the tradition of giving that was so much a part of who Samuel and Emily Williston were. It has become a major element in the School’s annual Advancement effort. On February 20, 2019, our goal was to inspire 1,178 donors — for Williston’s 178th year. Achieving that participation target triggered an additional $75,000 challenge grant, while several classes and the Williston Parents created incentives of their own. By the end of the day we had vastly exceeded expectations, as nearly 1,400 alumni, parents, faculty, students, and friends realized almost $400,000.

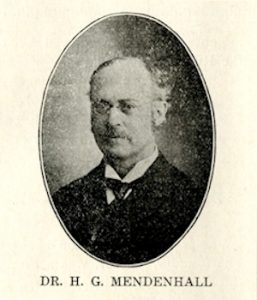

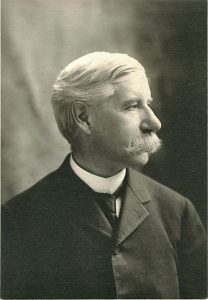

For Headmaster Joseph Henry Sawyer, who joined the faculty in 1866 and led the school from 1884-1886 and 1895-1919, Founders’ Day was especially meaningful. After all, he had known Emily and Samuel Williston personally, as well as most of the other major figures from the school’s early years. In 1911 his friend Herbert M. Plimpton, class of 1878, published several of Sawyer’s Founders’ Day addresses.

June 17, 1909, fell on the same day as Commencement, so much of the traditional Founders’ Day speechifying was curtailed. But Sawyer, in his graduation remarks to the senior class, included a few words —actually, more than a few — about Samuel Williston. While the religious element Sawyer evokes is de-emphasized in 21st-century Williston Northampton, much of what Sawyer had to say seems especially relevant for students and alumni today. The text, from Plimpton’s compilation, is reproduced below. (Please click the images to enlarge them.)

x

x