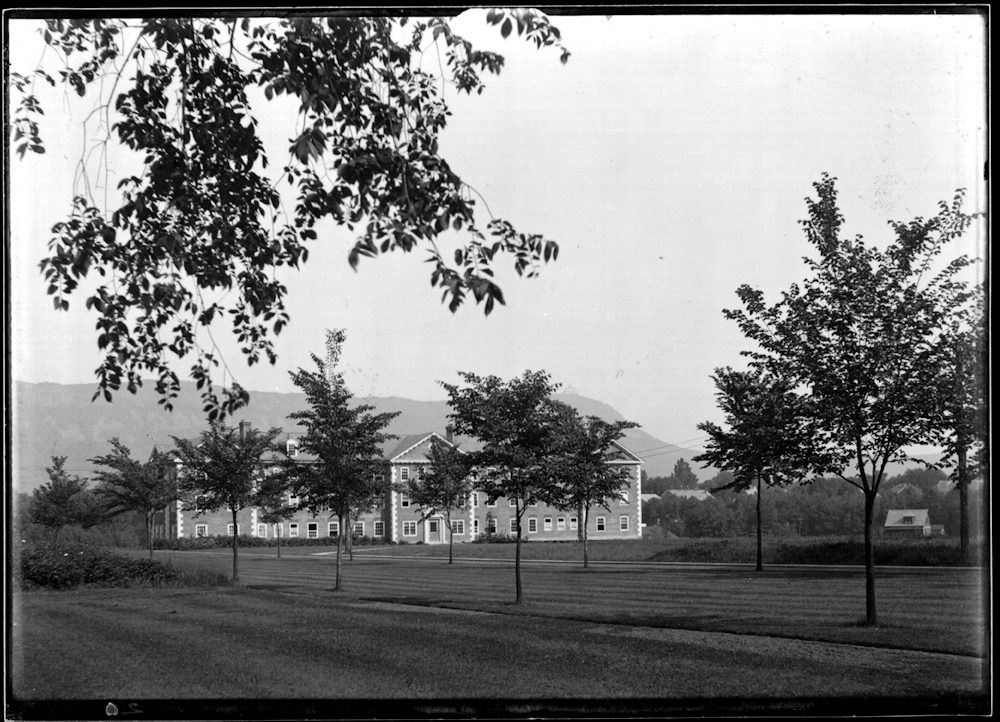

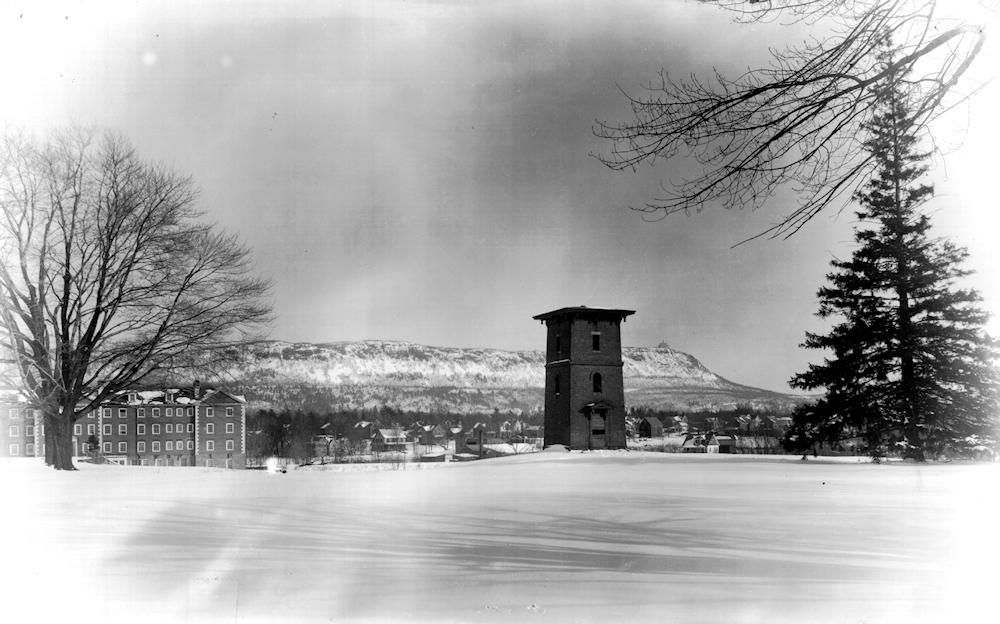

Williston Northampton is 175 years old this year. But almost forgotten amidst the dodransbicentennial [yes, it’s a real word!] hoopla is another milestone: Ford Hall opened a century ago this fall.

After the Homestead, it is the first structure to have been built on the so-called “new” campus. The Senior Dorm. (Not any more.) The Gold Coast. (No longer.) The Fraternity. (Ditto — perhaps, perhaps not.) Even in these unsentimental twenty-teens, some students — many of them the sons of alumni — will claim that to live in Ford Hall is to have arrived. It goes without saying that their non-Ford peers might not agree.

But if any campus building can be said to embody Tradition, with a capital T, it must be Ford. No doubt some individual traditions are best left unrecorded in a family publication like the From the Archives. Alumni of various generations will recognize references to the Phantom, those “useless” fireplaces, the Bomb Sight, the Great Newspaper Caper, Couchie’s Carlings, and the mythical Kid Who Was Taught His Colors Wrong. If you have to ask, you weren’t there.

On the other hand, readers who were there are invited to add their favorite Ford Hall stories to the comment form at the bottom of this article. What, after all, is a history blog for? Be advised, though, that publication is likely, unless you’ve forgotten that there is no statute of limitations on good taste.

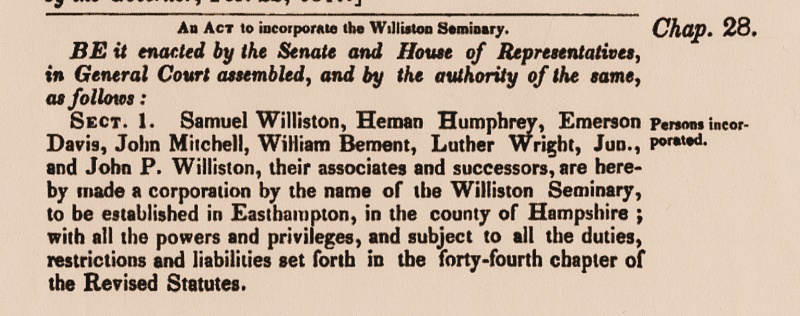

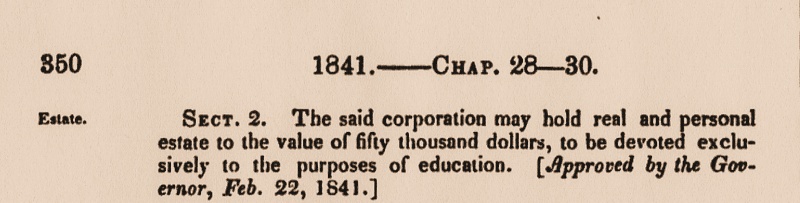

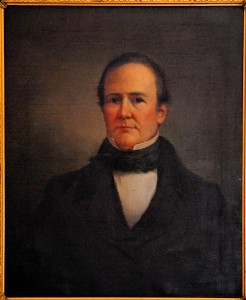

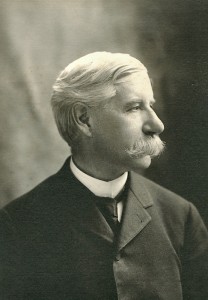

It is hard to imagine that a structure so much a part of the fabric of Williston Northampton life was almost never built. Samuel and Emily Williston’s estates had provided an endowment for the operation of the school, which was originally situated at the head of Main Street, on a site now occupied by two banks and a supermarket. Emily’s will conveyed the Homestead and surrounding land — the present campus — to Williston Seminary, with the proviso that the school erect at least one new building on the property. Continue reading

When I drive to work, I usually come down Brewster Avenue. As I turn onto Park Street, I see the iconic Class Fence, stretching out of sight in both directions, each section with the date of a graduating class. 173 of them, so far, going back to 1842.

When I drive to work, I usually come down Brewster Avenue. As I turn onto Park Street, I see the iconic Class Fence, stretching out of sight in both directions, each section with the date of a graduating class. 173 of them, so far, going back to 1842.

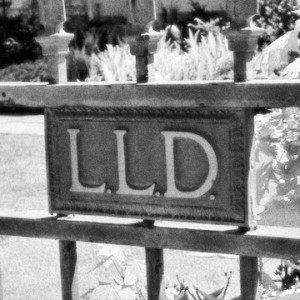

And the mysterious “L.L.D.”? They were one of Williston Seminary’s fraternities. We don’t know much about them; they were a secret society that kept its secrets well. The frats were wisely abolished in 1926-28, but not before the L.L.D. alumni achieved a kind of immortality by pledging and contributing to the fund.

And the mysterious “L.L.D.”? They were one of Williston Seminary’s fraternities. We don’t know much about them; they were a secret society that kept its secrets well. The frats were wisely abolished in 1926-28, but not before the L.L.D. alumni achieved a kind of immortality by pledging and contributing to the fund.