June — the seniors have graduated, the underclassmen have finished assessments (which are what we at kinder-gentler Williston used to call “exams”), and a lazy green quiet has settled onto the campus. Our parting shot to our returning students: “Goodbye, and don’t forget your summer reading!” It has been so for nearly a century.

I have a confession. Back in the summer of 1966, prior to my entering Williston Academy’s 9th grade, I was handed a list of perhaps half a dozen books. Now, I loved to read, almost at the expense of any other summer activity. And there was good material on the list, most especially Walter Edmonds’ Drums Along the Mohawk, which was an exciting story, although in retrospect, I don’t recall its subsequent mention even once in David Stevens’ English 9. But also on the list: Henry David Thoreau’s Walden. Now imagine yourself in 1966, as a 13-year-old boy who has recently discovered the works of Ian Fleming and is anxious to get back to them (albeit under the covers with a flashlight), but is faced with endless pages of prose about living in the woods and planting beans. I tried. I really did. But I couldn’t do it. And in the ensuing 51 years, I’ve tried several more times but, apparently scarred by my adolescent experience, I still find Walden barely readable. I think of Thoreau as the guy who put the “trance” in “transcendentalism.”

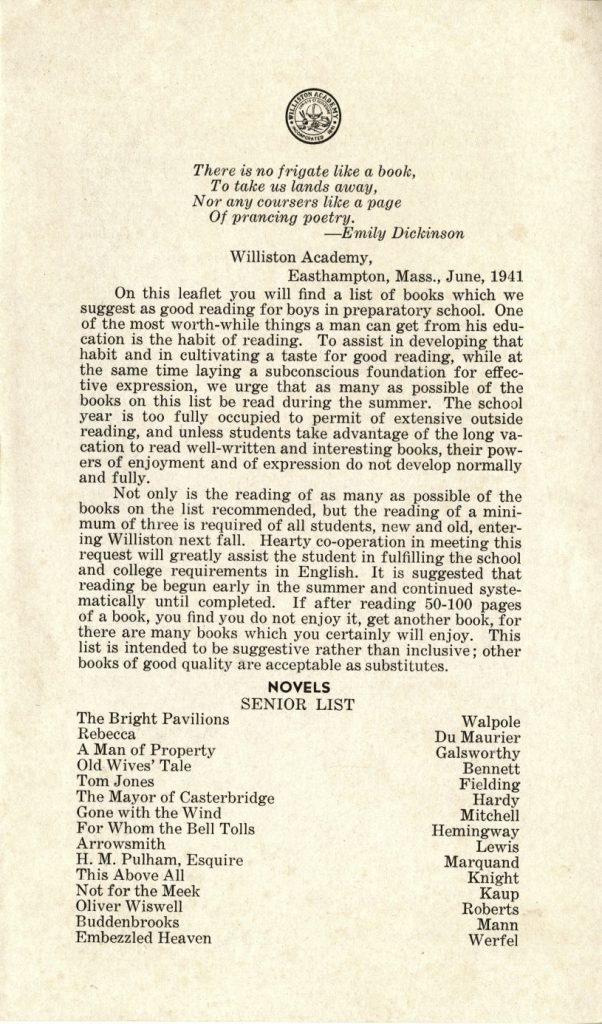

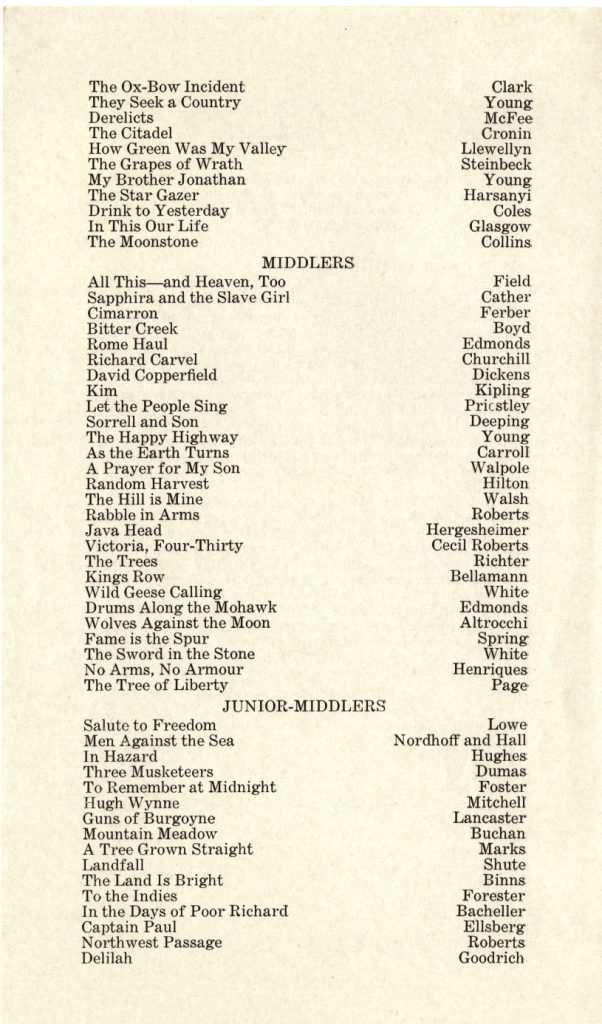

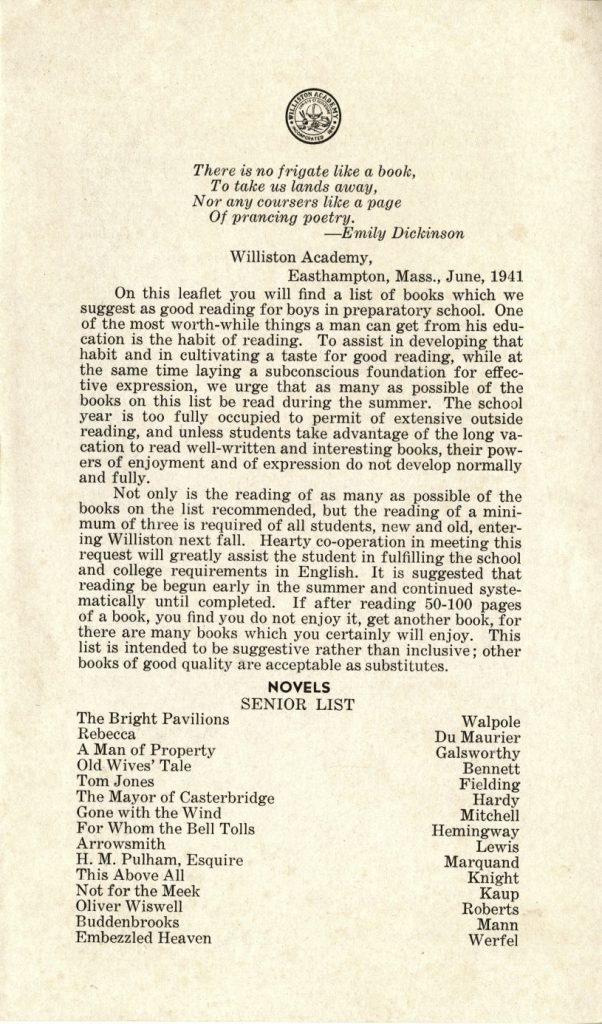

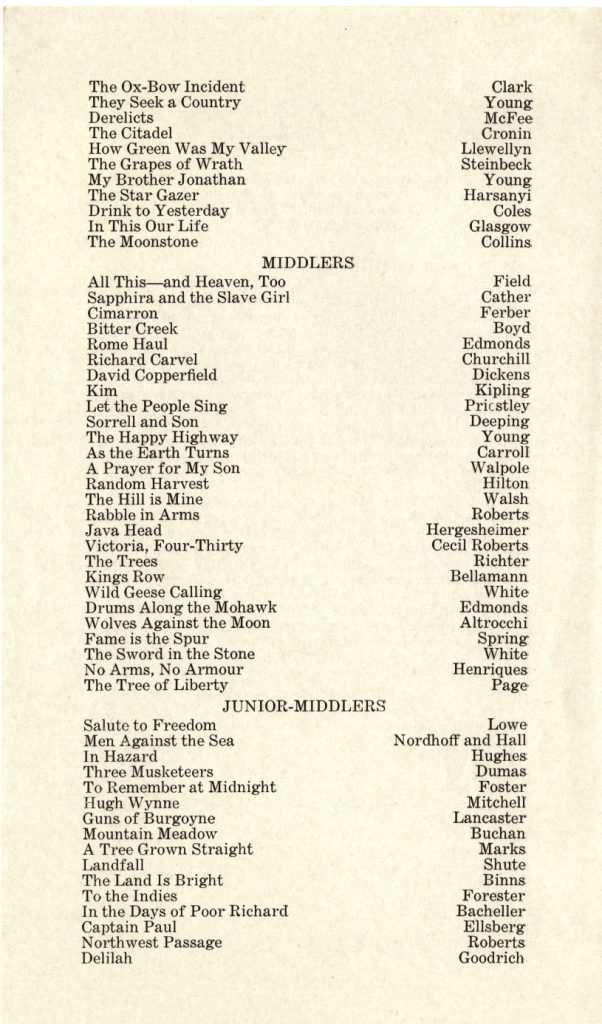

A summer reading requirement at Williston appears to date from the 1920s. No syllabi have surfaced from that early date. However, we have a list from 1941, which is worth reproducing in its entirety. (Please click images to enlarge).

Once one gets past the still-valid point about a “foundation for effective expression,” as well as whiff of testosterone, one notes that the requirement – a minimum of three books – isn’t especially onerous, despite a suggestion (“hearty cooperation”) that one attempt “as many as possible.” Where something doesn’t appeal, students are encouraged to move on. And nowhere is there even a hint of a test or paper in the fall.

Once one gets past the still-valid point about a “foundation for effective expression,” as well as whiff of testosterone, one notes that the requirement – a minimum of three books – isn’t especially onerous, despite a suggestion (“hearty cooperation”) that one attempt “as many as possible.” Where something doesn’t appeal, students are encouraged to move on. And nowhere is there even a hint of a test or paper in the fall. It is interesting to note what is, and isn’t, here. So many of these authors have fallen utterly out of fashion, never mind out of the canon, that some names are unrecognizable even to a pre-elderly librarian. And with few exceptions, almost everything is by American or English authors, the overwhelming majority of them male, and only one identifiable as an author of color. Continue reading →

It is interesting to note what is, and isn’t, here. So many of these authors have fallen utterly out of fashion, never mind out of the canon, that some names are unrecognizable even to a pre-elderly librarian. And with few exceptions, almost everything is by American or English authors, the overwhelming majority of them male, and only one identifiable as an author of color. Continue reading →

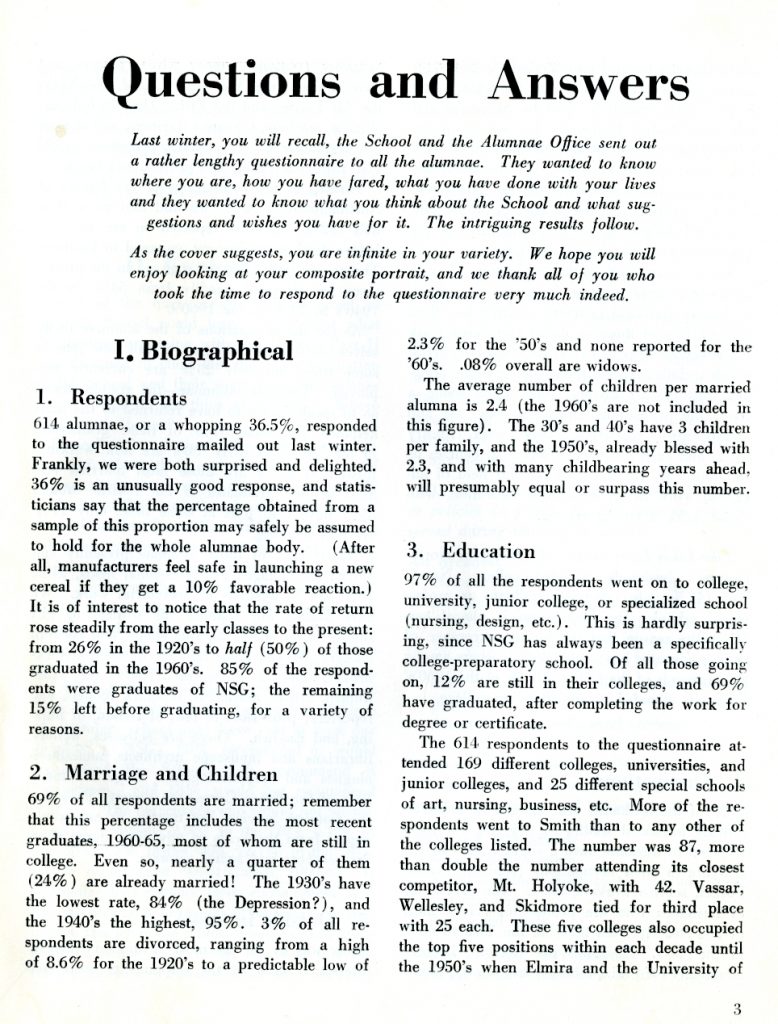

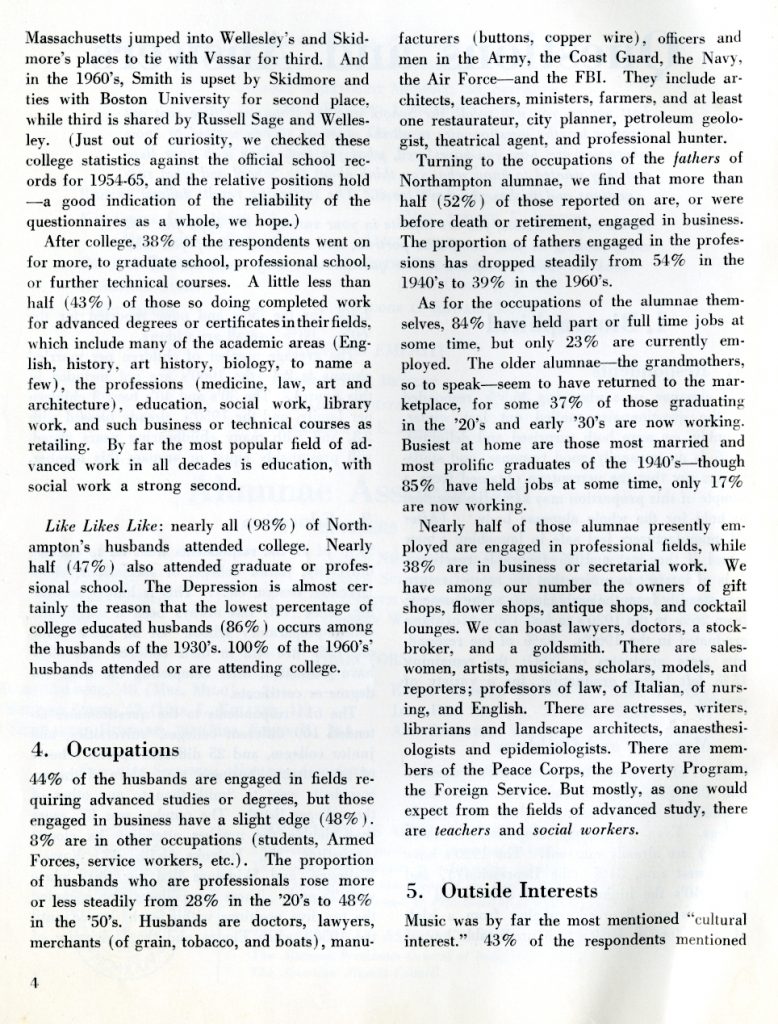

That report is reproduced here in its entirety, without further commentary. We’ve included a few additional photographs mostly because we like them, and they break up the page. They’re not meant to illustrate any particular narrative. (As always, please click each image to enlarge.)

That report is reproduced here in its entirety, without further commentary. We’ve included a few additional photographs mostly because we like them, and they break up the page. They’re not meant to illustrate any particular narrative. (As always, please click each image to enlarge.)