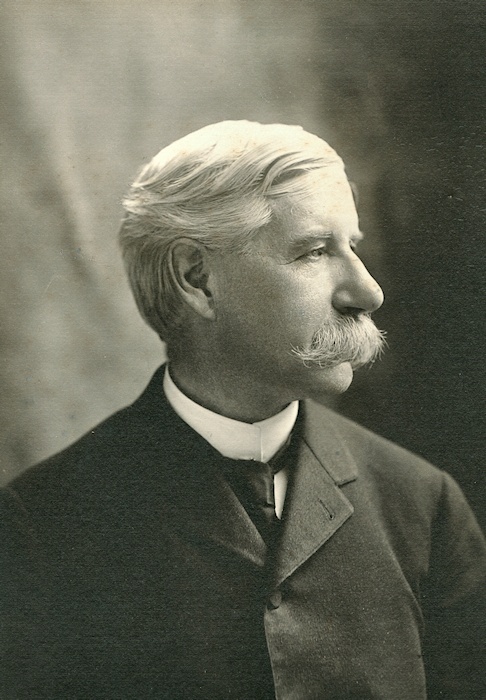

“A tall spare man slightly stooped with untrimmed gray moustache and formal tail coat was for long years a familiar figure to both campus and town. He was one of those persons who was always going somewhere, always on duty, and not given to casual conversation. ‘See me in my office’ was his characteristic invitation . . . ‘Old Joe’ was a host in himself. And what a complex of competing interests: schoolmaster who wanted to be a preacher, strict disciplinarian whose heart was always giving way before a youngster’s tearful plea, living laboriously in the present and yet clinging wistfully to a past long since gone by, most serious of countenances lightened at times with the pleasantest of smiles.” (Howe, 1)

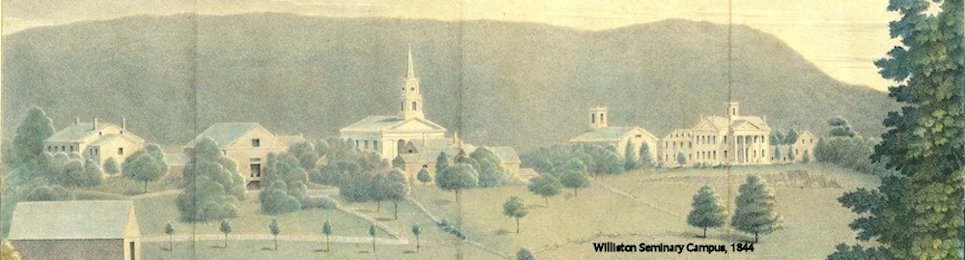

Joseph Henry Sawyer. Williston’s longest-serving faculty member was here for 53 years, a record that no one else has even approached. That could simply be another piece of Williston lore, like the numbers on the fence or the cow in the tower, were it not that Sawyer took himself seriously as an historian and wrote a useful history of the school. He counted Samuel and Emily Williston among his friends. He knew all six of his predecessors as Principal or Headmaster, as well as his successor, Archibald Galbraith. There are hundreds of living alumni, this writer included, who knew Galbraith. His life is a kind of time travel, a bridge between centuries. So Sawyer’s longevity is enough to warrant our interest, but there is much more.

He had really hoped for something other than teaching. Though conservative by instinct and by preference, he became our most innovative Headmaster, although he had never sought the job.

Background

In advance of the Williston centennial in 1941, Herbert B. Howe, class of 1901, attempted a Joseph Sawyer biography. Howe was a competent historian and indefatigable researcher. Yet he found Sawyer to have been so self-effacing that his life away from Williston was nearly undiscoverable. The son of farmers, Sawyer was born May 29, 1842, and raised in Davenport, Delaware County, New York, some 70 rural miles southwest of Albany. Young Joe did well enough at school for his parents to agree to send him for one year to the nearby Fergusonville Boarding Academy. There, Sawyer discovered the joys of the laboratory and the library. Against his nonetheless proud parents’ expectations, Sawyer won a scholarship to Amherst College. Arriving there in 1862, he found that he was sufficiently advanced to be granted sophomore status.

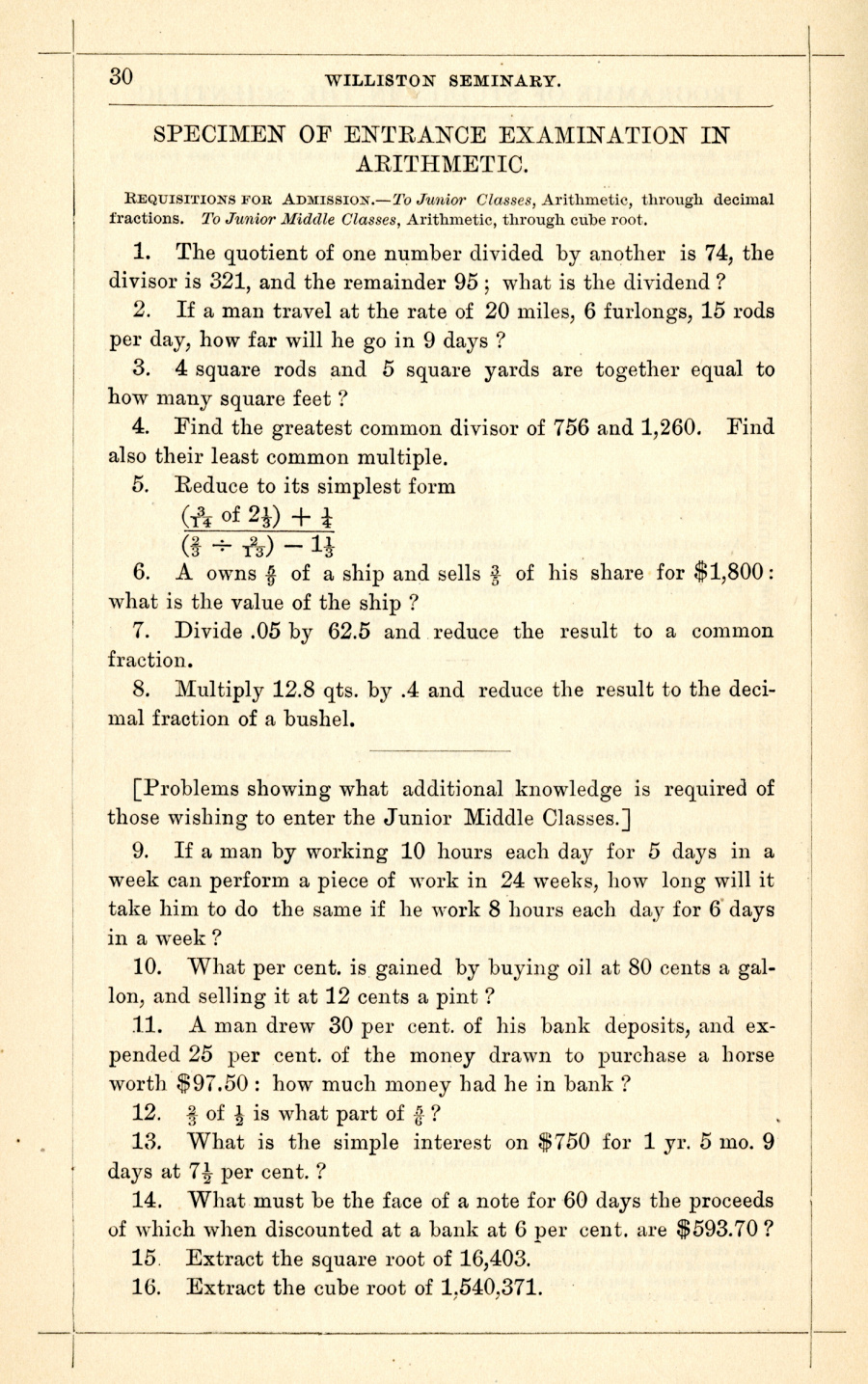

He graduated in 1865, a member of Phi Beta Kappa and in a three-way tie for Valedictorian. Along the way he had decided to become a clergyman. However, this would require graduate study which, at the time, Sawyer could not afford. Having excelled in mathematics, he took a teaching position at Monson Academy, now Wilbraham and Monson.

A year later, Principal Marshall Henshaw, himself an 1845 Amherst graduate, hired him to teach at Williston Seminary. The road between Amherst and Easthampton was well-traveled in both directions. Many Williston graduates went on to Amherst – 14 of Sawyer’s 57 classmates had prepped there. Many returned to Easthampton to teach. Samuel Williston was an Amherst trustee. It is not impossible that Henshaw and Sawyer knew one another; at the very least, Henshaw was likely to have known that Sawyer was among the elite scholars in his class. So when teacher Judson Smith (Amherst ‘59) decided to move on, Amherst Mathematics Professor Ebenezer Snell recommended Sawyer to replace him.

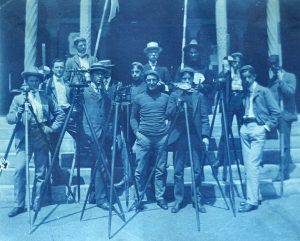

Sawyer was hired as a teacher of pure and applied mathematics and something called “mental philosophy” — we now call it psychology, plus economics and history. Later in his career he would teach surveying and English. Teachers had to be multi-talented in those days. They had to be tireless, as well; the typical course load was six one-hour classes, every day.

Sawyer was 23 years old. One never knows how long young faculty will stay. Then, as now, many would teach for a couple of years and go on to grad school, or decide that teaching wasn’t for them, or find a school with greener grass. His initial plan appears to have been to recover his finances and then resume his education, but for whatever reason – and Sawyer is characteristically silent on his motives – he stayed.

Continue reading