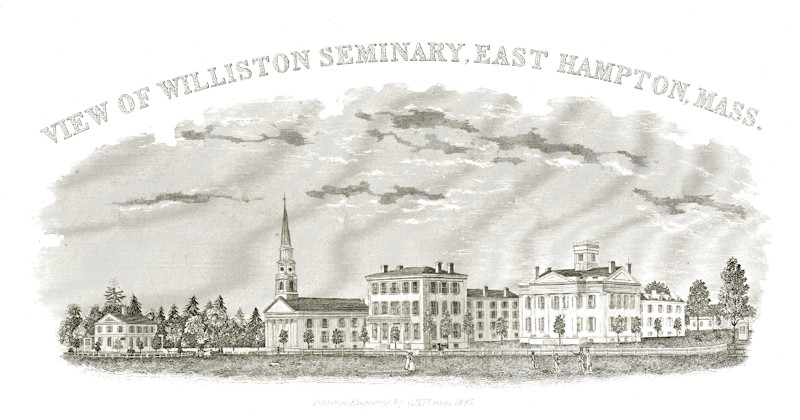

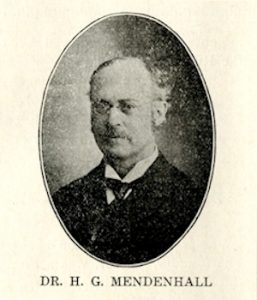

In the fall of 1931 the Reverend Dr. Harlan G. Mendenhall, Williston Seminary class of 1870 (Classical), visited the campus. Aged 80, Mendenhall was considered the “grand old man” of American Presbyterianism, having served in parishes all over the U.S., risen to the highest levels of the New York Presbytery, and was, in 1931, still not retired. Dr. Mendenhall brought with him a variety of documents from his student days, including a copy of the 1869 Salmagundi, Williston’s first senior yearbook, which he had co-edited, and a scrapbook of his student writings as a member of Adelphi, the school’s literary and debating society. He also sat down with The Willistonian for an extended interview, reproduced at length in the issue of October 21. Conversation focused on how the school had changed in more than five decades – and took a surprising turn.

“Williston in my day was a great deal different than your Williston of today. North Hall was but a few years old and was all partitioned off into three sections by thick fire walls. There were no bathrooms nor any central heating system, and in the winter we all had to buy our own coal for our stoves. We had no school dining room either and had to eat either at fraternity eating places or at the old “Hash Factory” which stood at the corner of Union and High Streets. It was possible to eat for two dollars a week then.”

“Students were then a great deal older than the fellows at Williston are now. There was one fellow named Redington who had already graduated from Yale and had come to Williston to study English. As the boys were older, they were more independent and often used to have revolutions and uprisings of all sorts.”

[Lyman William Redington of Waddington, N.Y. graduated Williston’s Classical Department in 1866. He completed a year at Yale, left because of eye problems, but returned to Williston and enrolled in the Scientific, a.k.a. English Department, graduating in 1869. He and Harlan Mendenhall were the founding co-editors of the yearbook Salmagundi in 1869. He became a newspaper editor in Rutland, Vt., ran unsuccessfully for Governor, took up law, and ultimately became Asst. Corporate Counsel for the City of New York, and a Tammany Hall member of the State Assembly.]

“There was a fellow in school then who had received a check for one hundred dollars from home, and instead of depositing it in the bank, he took it across to Putnam’s Book Store and established a checking account.”

“There came a time when Ballance, that was the boy, [William Henry Ballance, class of 1870] said that he had ten more dollars coming, and Old Put claimed that he had drawn his entire account. Then Ballance started an association of most of the boys in school swearing not to trade with Put until the ten dollars should be paid. They formed a big parade and marched down in front of Put’s store and read the constitution and by-laws of the association to him. Some of the boys carried big banners inscribed ‘No More Trade for Old Put’ and ‘False Weights Against True Ballance.’ The parade then marched over to the gym steps and had its picture taken.” Continue reading