Though not a Williston alumnus, arguably Lewis Miller (1919-2008) headed a Williston Northampton dynasty. He and his bride, Jean Douglas Miller ’36 (1918-2005), sent five children to Northampton School for Girls or Williston Academy. Two generations of descendants have attended since. Jean’s brother Richard Douglas ’41 (1923-2007) was the unwilling hero of the following memoir.

Playwright, actor, and journalist, Lew Miller knew how to tell a story. He penned this one for his children and grandchildren in 1992. Recently Elizabeth Miller Grasty ’66 shared it with David Werner of the Williston Office of Advancement, who passed it on to the Archives. It is reproduced here, with some editing, with the kind permission of Ms. Grasty. — RLT

The Poet and the Dribble Glass

by Lewis W. Miller

As Robert Frost approached Easthampton, Massachusetts, one evening in 1938, he would not have been in the mood for jokes. Certainly he was not expecting to be the butt of a practical joke. Elinor White Frost, his wife of 43 years, had died suddenly only two months before. Further, he had decided to resign his long held position at Amherst College. Frost, at age 64, had entered a bleak period of his life which seemed to him without hope.

His reason for visiting Easthampton, that Tuesday, May 27, was to fulfill a long-standing commitment to an old friend, Archibald Galbraith, Headmaster of Williston Academy. Each spring for many years, Frost had given – at Galbraith’s invitiation – a reading of his poems for the students.

The student who was destined to confront this world-famous Pulitzer Prize winner was Richard Knowles Douglas. He was a diffident 15 year old unlikely to indulge in practical jokes – especially on an adult. Richard (nicknamed “Red” at school) had a busy life ahead: Amherst College, Albany Medical School, U.S. Navy M.D. with the Marine Corps, followed by a long, fruitful, still-continuing career in the practice of surgery in his home town of Westfield, Mass.

1938 was the year in which Adolf Hitler forcibly annexed Austria. Franklin Delano Roosevelt was in his second term as President of the United States with “Cactus Jack” Garner of Texas as his Vice President. Charles Hurley, Democrat, was serving his only term as Governor of Massachusetts. Williston Academy, in its 97th year, was planning to celebrate its centennial in 1941. Red Douglas may possibly have forgotten such highlights of the year. But he never quite forgot the trauma of the evening ahead.

Dinner was served as usual in Payson Hall to students living in South and North Halls. A master and eight students were waited on at round tables by “scholarship boys.” Latin Master Lincoln DePew Grannis (“Granny”) usually said the grace before meals. The food was described as “bullet-proof – everything but tasty.” The Saturday night menu never varied: one boiled hot dog, one slice of Boston brown bread, baked beans, milk, and water. Presumably the food served at Ford Hall, a new dormitory on the New Campus, was more appealing. The cost of boarding there was higher.

Soon after dinner the hundred or so boys attending Frost’s reading gathered in the Dodge Room. Most of them were seated on the floor of this handsomely paneled room in the New Gymnasium. The poet referred to his readings at schools and universities as “Barding Around.” Years later, when asked which poems were presented that evening, Douglas replied, “All of them – no explanation or discussion, he just read – seemed on an ego trip.”

When Frost had been reading for one and a half hours, a student broke wind. This occasioned embarrassed laughter among his fellows, to which the poet responded, “Would you like me to go on?” Hearing no answer, “Very well, I will continue.” This he did, for another half hour!

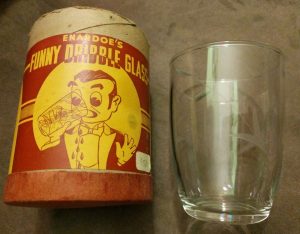

At the close of the evening some two dozen especially invited boys joined Frost in the Headmaster’s House for refreshments. Mr. Galbraith inquired of Frost his choice of beverage. A glass of milk was requested. “Gally,” as he was called by the students behind his back, turned to young Douglas nearby, asking him to bring a glass of milk for the famous guest. In the kitchen a maid (“She never liked me,” recalled Douglas years later) poured the glass of milk, placed it on a tray, and handed it to Red, who served it to Robert Frost. Frost took a drink and spilled milk down his tie and shirt. “How clumsy of me,” he murmured, as he wiped the spill with his handkerchief.

A second drink resulted in an even greater spill. Seeing this from across the room, Galbraith “came down like a locomotive” heading for the hapless Red. “Was this done on purpose?” Galbraith demanded angrily.

“No, sir,” the student answered – fully expecting to be thrown out of school. The Headmaster’s response was not complimentary. Red returned the dribble glass to the kitchen. There, the Headmaster filled a fresh glass while the shaken student attempted to exonerate himself. “This is not my fault. I have never even heard of a dribble glass!”

Red’s explanation may have been believed, but most likely he was allowed to remain in school because Archibald Galbraith held the boy’s father, Archibald Douglas, in high regard. Robert Frost graciously accepted the apology required of Red, who was then permitted to depart for his dormitory room.

Holding no grudge, Robert Frost returned to Williston each spring for more “Barding Around,” at least until Red Douglas graduated in 1941. The record does not state whether Red continued to attend the readings.

Skeptical? Oddly, I’m not. The story is, of course, really by Richard Douglas, merely transmitted by Lew Miller. There is substantial detail, but at no point does the narrator make the extravagant claims of the sort alumni indulge in when they reminisce about “good old days” — that stuff, I tend to take at about 50% (unless I’m telling the story). No one, more than 50 years after the event, claims or is given credit for the joke. And who might it have been? It would be easy to blame the maid, who actually produced the glass and poured the milk, except that it is unlikely she would have dared. Can it be that Frost was never the intended victim, rather that someone had spirited the glass into Galbraith’s kitchen, hoping to catch the Head himself?

Frost’s visit was duly reported in The Willistonian of June 3. There is no mention of anything untoward, but a rather nice irony in his chosen theme.