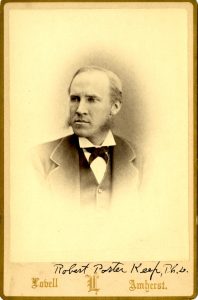

In the fall of 1876, a new Principal, James M. Whiton, arrived at Williston Seminary. One of his first acts was to hire an assistant, Dr. Robert Porter Keep (1844-1904), at 32 a rising star among classical scholars. The two of them announced their intention to modernize Williston’s innovative dual-track Classical and Scientific curricula. This attracted the attention of Keep’s friend, the critic, author, and editor Horace E. Scudder (1838-1902). Scudder was preparing a study of New England private schools, and must have visited Williston at about this time. In his article, “A Group of New England Classical Schools,” in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine (Volume 55, June to November, 1877, p. 562-570 and 704-716), he asserted that with some curricular tweaking, particularly in the Seminary’s unique Scientific Division, Williston could join the pantheon on what Scudder considered education’s Olympus: Andover, Exeter, Saint Paul’s, and Boston Latin.

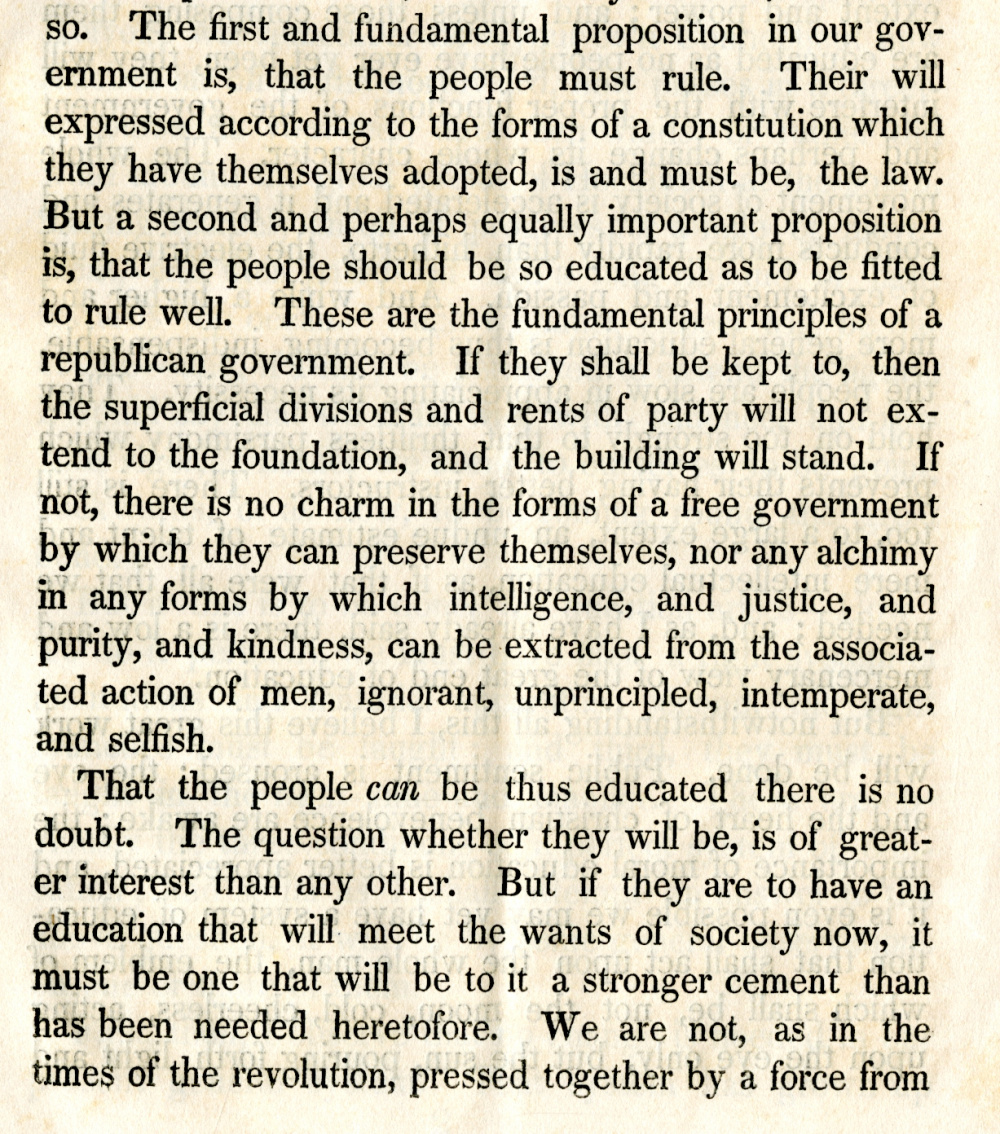

Scudder advocated adding the study of English to the curriculum. It is hard to believe today, but Williston students of the time took only one literature class, plus weekly or monthly meetings in English fundamentals. Appreciation of literature was largely absent from the Scientific curriculum. The Classical scholars got plenty of it — but solely in the Greek and Latin classics.

Keep was clearly intrigued, and appears to have written to Scudder asking him to elaborate. One challenge would have been to create a framework that accommodated the different needs and backgrounds of Williston’s Classical and Scientific students. Scudder, in his long-delayed response of April, 1878, addressed this and more in the following letter. It is a remarkable document, presenting a surprisingly modern approach to the study of reading and writing.

[Note: In transcribing the manuscript, I have retained Scudder’s punctuation and included crossed-out text. Editorial additions are in [bracketed italics]. Where a word was unclear, I have placed it in [brackets?] with a question mark. – R.T.]

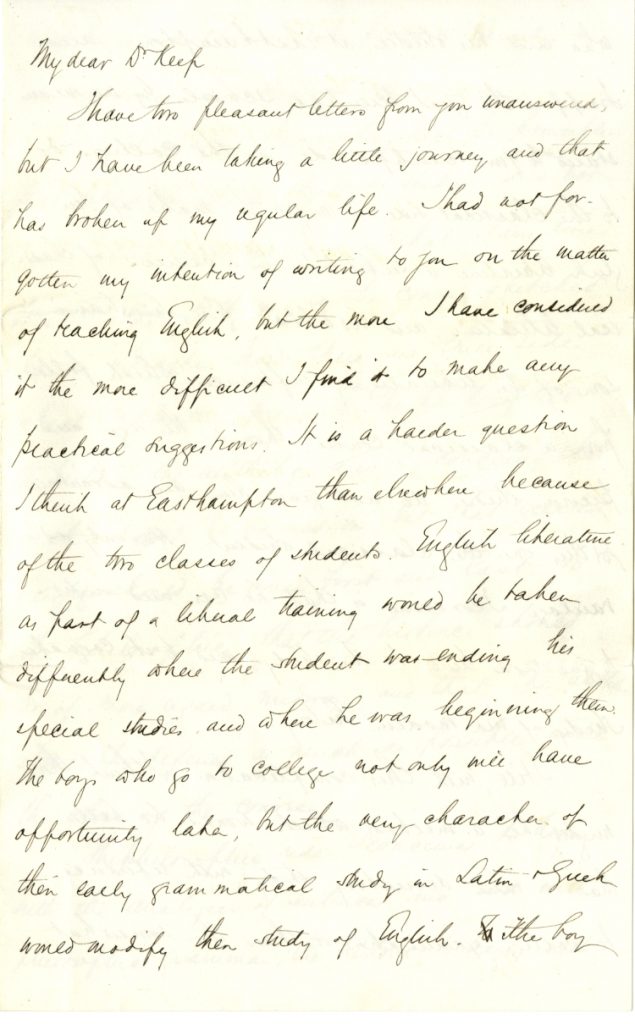

My dear Dr. Keep,

I have two pleasant letters from you unanswered, but I have been taking a little journey, and that has broken up my regular life. I had not forgotten my intention of writing to you on the matter of teaching English, but the more I have considered it the more difficult I find it to make any practical suggestions. It is a harder question I think at Easthampton than elsewhere because of the two classes of students. English literature as part of a liberal training would be taken differently when the students was ending his special studies and when he was beginning them. The boys who go to college not only will have opportunity later, but the very character of their early grammatical study in Latin & Greek would modify the study of English. The boy who ends his studies at Easthampton – and I suppose the great Scientific schools by no means stand to your scientific side, as the colleges do to the classical side – ought to make of English literature a substitute, in a degree, of classical literature, and to obtain from his training some of the liberalizing influences which follow from a classical course, though his age and previous studies do not give him any advantage for this over the classical student. His only advantage I conceive is that he can and ought to give more time to the study and to its cognate study of modern history.

Still, with this complication, I think there might be a method which would be better than a mere desultory study with reference to college examinations, or than the somewhat haphazard method which prevails largely in our academies and high schools.

First of all I would lay down the principle that literature itself should be studied and not books about literature, and in that I am sure you will agree with me as the course sketched by you indicates. Now there are three sides which literature presents, the philosophic, the historic, the aesthetic, and I conceive that each should be carried on, but that greatest weight should be given first and last to the philosophic, that the historic should be of more [regard?] midway, and that the aesthetic should be deferred as much as possible until the close of the course.

The philosophic side I conceive to begin with the analysis of sentences and with philosophic grammar; the historic to begin with the history of words and with the political and social connexions of literature; the aesthetic to begin with a discrimination of forms of literature and end with conceptions of its art, in harmony with other forms of creative work. Continue reading