Early Coeducation at Williston Seminary

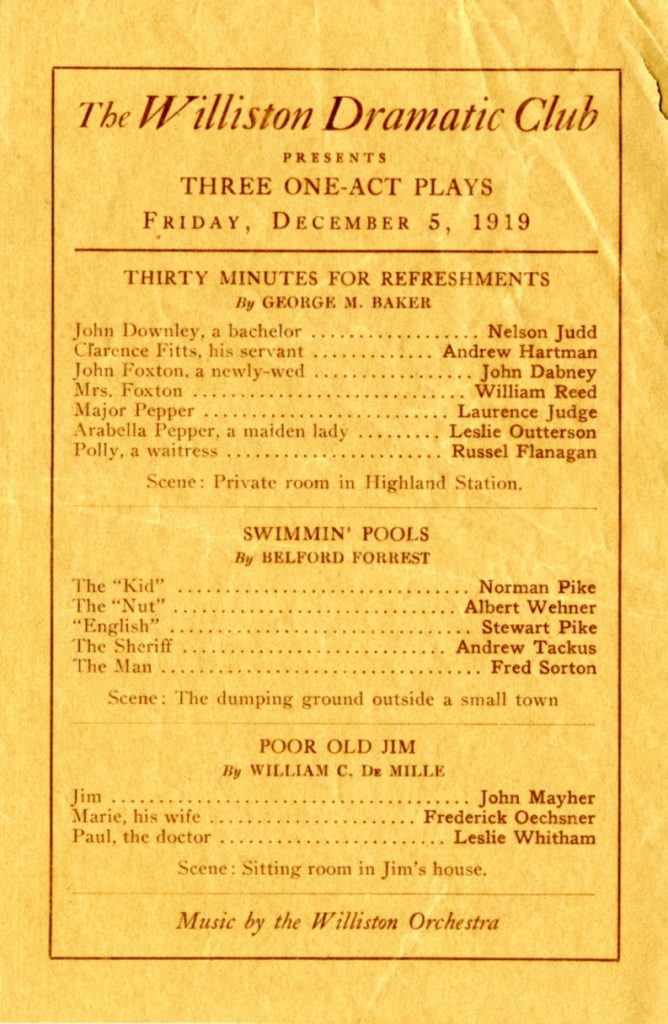

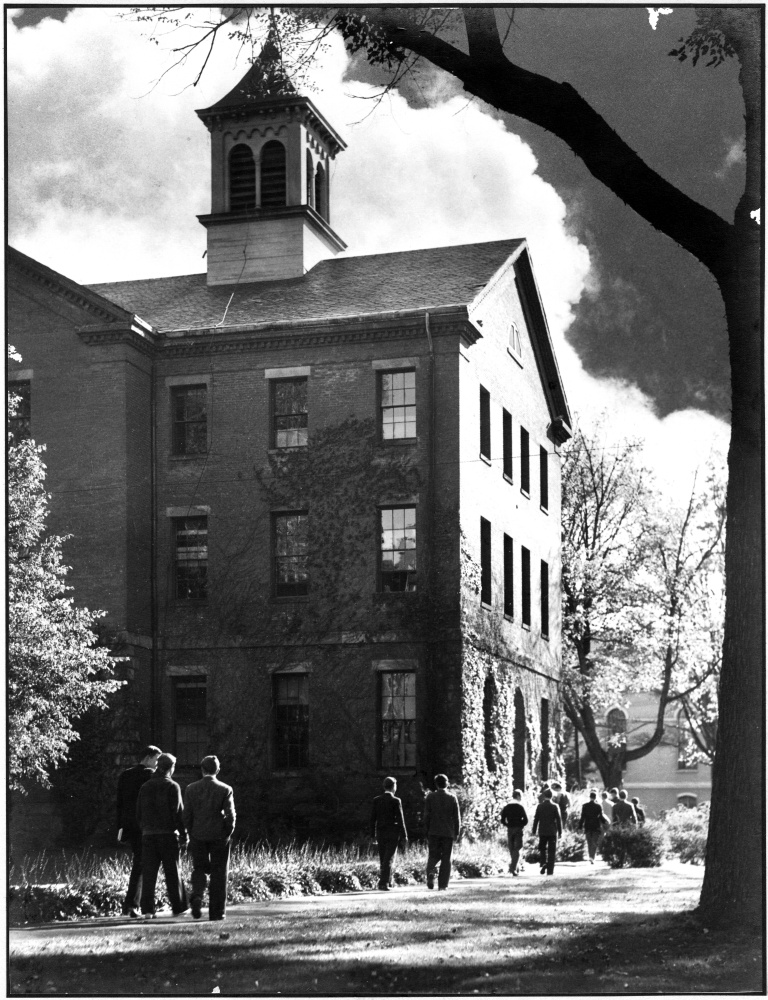

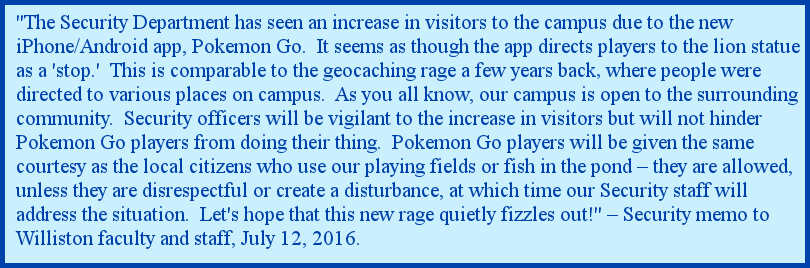

September 2021 will mark a true milestone in school history: exactly 50 years earlier, Northampton School for Girls and Williston Academy, newly merged, opened as the fully coeducational Williston-Northampton School. That story is told elsewhere (see Northampton School for Girls – and After). It wasn’t always an easy transition – a few years later, according to legend, the hyphen was legally dropped from the school’s name after a highly placed administrator, in an ill-timed jest, suggested it represented a minus sign. Times have changed, and we are preparing to celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of coeducation at Williston Northampton.

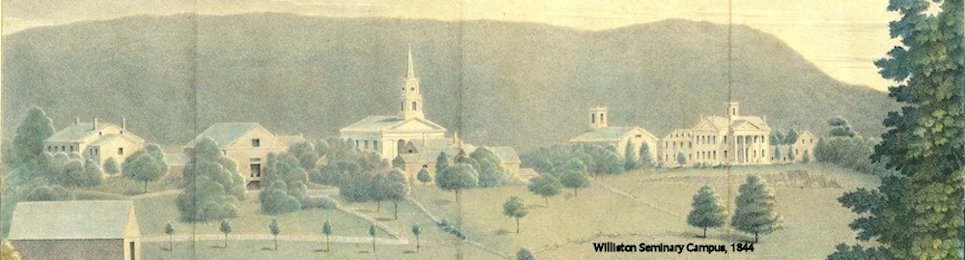

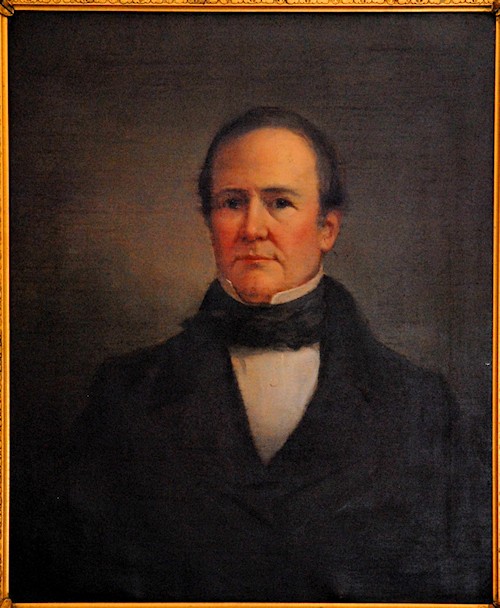

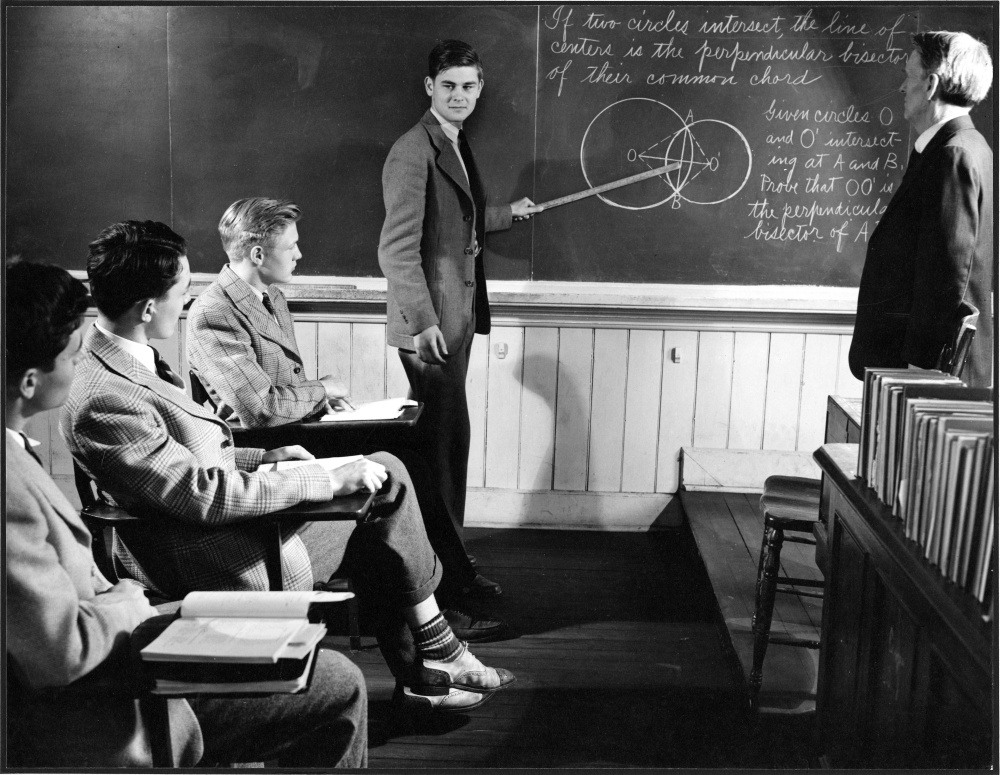

Few, perhaps, are aware that in 1841, 130 years before the merger, Williston Seminary had opened as a coeducational school. Part of Samuel Williston’s motivation for founding the Seminary was that Easthampton had no high school. Poor eyesight had forced him to curtail his Andover education, and Williston, already on the road to becoming Easthampton’s principal municipal benefactor, must have wondered whether, had there been educational opportunities closer to home, things might have been different. Williston was also acquainted with the great Massachusetts educational reformer Horace Mann, a pioneering advocate for the education of women. (For biographical information on Samuel and Emily Williston, see “The Button Speech.”)

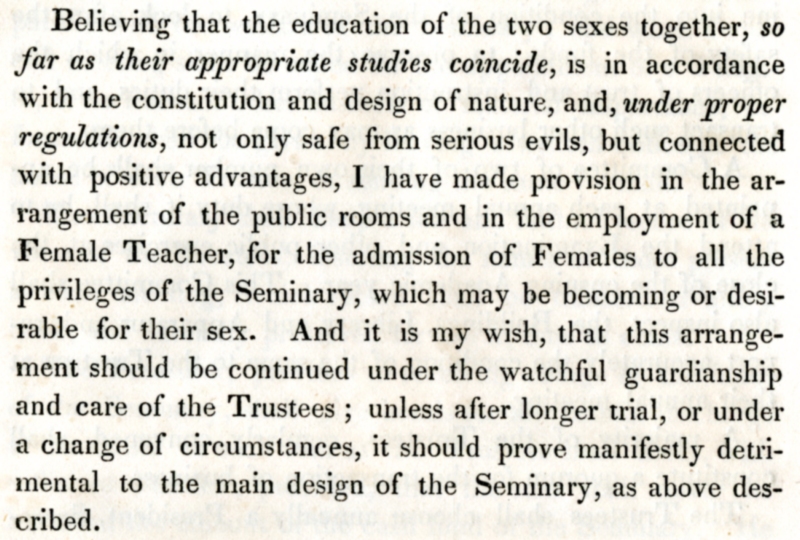

There are suggestions, though, that from the beginning, Samuel had misgivings about coeducation. His original inspiration had been the great English public (i.e., private) schools, notably Rugby, all of them bastions of maleness. The bylaws of Williston Seminary, published in 1845 but in effect from incorporation, stated,

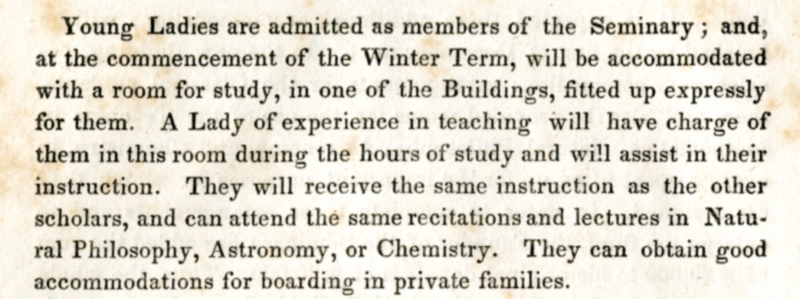

When classes first convened in December 1841, there were 192 scholars, 53 of them – 27% – young women. The Seminary’s literature made it clear that young women had access to all the curricular resources of the school. The Annual Catalogue of 1844 notes,

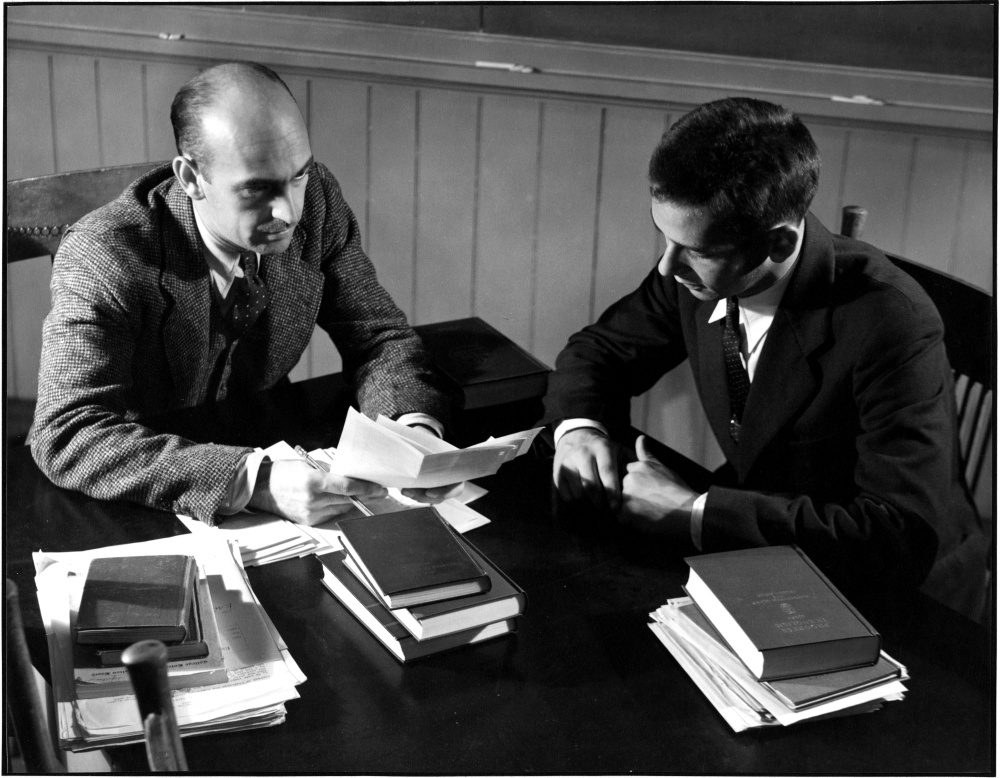

So far, so good. But as the passage specifies that young ladies might attend the lectures in the sciences, it implies that the “same instruction as the other scholars” was taught separately by the “Lady of experience,” regardless of the subject matter. The “Lady” in question in the earliest years was one Miss Clarissa Stacy, listed in the Catalogues as “Teacher of the French Language.” In 1844 she was joined by Miss Sarah Brackett, who had the grand title of Preceptress. More often than not, over the next two decades of staff changes, the French teacher and the Preceptress were the same person. But only rarely did the Catalogue even acknowledge that individual as Preceptress, This was the case even in 1849-50, when Samuel Williston’s adopted daughter, Harriet Richards Williston held the job. Harriet, class of 1847, had no college education, having enrolled briefly at Mount Holyoke but withdrawn. Before becoming Preceptress, Harriet had also taught French, which she’d learned from Miss Stacy, from 1847-49.

In all but two instances we do not know the educational backgrounds of the nine women who served as Preceptress between 1844 and 1863. Besides Harriet, two others were recent alumnae of the Seminary. But it appears that the Preceptresses, occasionally assisted by another teacher, were responsible for every facet of the girls’ education outside the sciences, regardless of qualifications. This certainly calls into question how seriously the Seminary took its claim of “the same instruction.”

Continue reading