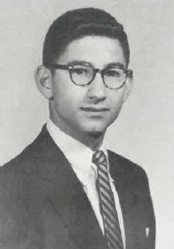

Charles A. Krohn, 88, died on January 8th, 2026 in Panama City Beach, Florida. The cause of death was cancer. He authored many articles about defense matters and wrote an acclaimed book about his experiences during the Vietnam War.

Mr. Krohn was born in Saginaw, Michigan on March 3, 1937, the fourth son of Raymond and Henrietta Krohn. Now in a state of urban decay, Saginaw boomed during the lumbering era of the late 1800s, and then received another boost when it became a manufacturing center, corresponding with the rise of the automobile industry in Michigan. The manufacturing boom of World War II survived until the early 1960s leaving behind an era of prosperity and optimism. The family owned and operated department stores.

Mr. Krohn was raised in Saginaw, leaving in 1953 to attend Williston Academy in Easthampton, Massachusetts. He was graduated from the University of Michigan in 1959, followed by a brief stint at Stanford Law School.

From his early days, Mr. Krohn showed a knack for things military, even posting map pins reflecting the location of his oldest brother Jim, then an Army sergeant serving in Europe during World War II. During the Korean War Mr. Krohn sent food parcels overseas to soldiers at the front, many who responded with letters of appreciation, often at the basic level of literacy. These letters were saved among his most important papers.

Mr. Krohn served two years in the Army, 1961-63, fulfilling an ROTC obligation. Most of this time was spent in South Korea, where he commanded a small advisory detachment at an isolated site near Uijongbu, now a suburb of Seoul. He often said this was the most maturing experience of his life.

Still hoping to find a career as a military writer, after leaving the Army he worked for the Flint (MI) Journal and United Press International in Chicago. Disappointed that UPI was slow to send him to Vietnam as a reporter, he accepted an invitation in 1967 to return to the Army as the public affairs officer of the 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile). After eight months he was unexpectedly invited to become the intelligence officer of an infantry battalion. His experiences with the infantry led to a book about the battalion’s exploits during Tet ’68.

The first version of the book, The Lost Battalion, was published to wide acclaim by Praeger in 1993, followed by an updated version published by the Naval Institute Press in 2008. A third version was published in 2009 by Simon & Schuster.

Being surrounded and escaping from a North Vietnam Army regiment influenced his decision to stay in the Army. Until his death, Mr. Krohn stayed bonded with those who shared his experiences in Vietnam.

Before returning to Vietnam in 1970 for a second tour, he married Jeannie (nee McLendon) whom he met at Fort Benning, Georgia while attending the Infantry Officers Advance Course. After Vietnam he served in various assignments in Germany and the United States, until his retirement as a lieutenant colonel in 1984.

Mr. Krohn’s career suffered an apparent setback when he was relieved of his responsibilities in the Pentagon in 1980 for transmitting to Army newspapers worldwide a medical article about circumcision, then considered a “taboo” word, at least in the view of his superior. Somewhat dejected, he was offered a position as speechwriter to the Army’s deputy chief of staff for personnel, the legendary General Max Thurman, father of the “Be All You Can Be” campaign. Instead of stepping back one step, his career took a giant leap forward.

His last active duty assignment was special assistant to the late General Richard G. Stilwell, then deputy undersecretary of defense for policy. After their respective retirements, the two operated a business together. General Stilwell was closely connected to President Reagan, CIA director Casey and Defense Secretary Weinberger.

During the last few years of his post-Army life, Mr. Krohn was a defense consultant and wrote often on military affairs for various publications. When George W. Bush was elected President in 2000, he named Thomas E. White as Army Secretary. Mr. White invited Mr. Krohn to return to the Army as the deputy chief of public affairs. But when Mr. White was fired by Defense Secretary Rumsfeld, Mr. Krohn realized he faced a dim future in the Pentagon. He volunteered to serve in Baghdad for a few months, at age 67 perhaps the oldest person then serving in the Green Zone.

After resigning his Army position, Mr. Krohn was invited by the University of Michigan to return to Ann Arbor as a visiting professor of journalism. After teaching for two semesters, he returned to the Washington, DC area and accepted a position with the American Battle Monuments Commission as deputy director for public affairs. His mission was to encourage more Americans to visit the nation’s 24 overseas military cemeteries.

Krohn often described himself as a cat fancier, smoker of fine cigars and consumer of good whiskey. His favorite hobby was reading history and watching Mrs. Krohn garden. He wished to be remembered, not as a retired soldier, but as a proponent of a strong national defense. While not rising to the highest echelons of responsibility, Mr. Krohn enjoyed the respect of his family and peers.

Mr. Krohn is survived by his wife; four sons, Cyrus, Joshua, and twins Clay and Alex; a daughter-in-law, Jennifer Krohn; a partner, Jennifer Martindale and son Zander; five grandsons, Maxwell, Oliver, Tristan, Sawyer, and Holden; and a granddaughter, Marjorie.